How often is our behavior non-purposeful, without intention, and without conscious awareness? How often is our behavior purposeful, intentional, and conscious of others’ well-being? I got to thinking about this subject the past few days, as I reflected on the theme of automatism. This post reflects upon the need for purposeful regard for other persons’ wellbeing if we are to experience human progress.

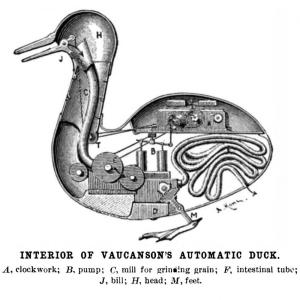

I mentioned “automatism” above. So, what is automatism? According to the American Psychological Association, automatism is “nonpurposeful behavior performed mechanically, without intention and without conscious awareness. It may be motor or verbal and ranges from simple repetitive acts, such as lipsmacking or repeatedly using the same phrase (e.g., as it were), to complex activities, such as sleepwalking and automatic writing. Automatism is seen in several disorders, including catatonic schizophrenia and complex partial seizures.”

We often wonder if what is called automatism is in play with our adult son, Christopher. For those not familiar with my son, he endured a catastrophic brain injury in January 2021. Christopher has since experienced some level of consciousness. And yet, many of his movements appear mechanical or the result of reflex action rather than intentional. It is not always easy to discern where conscious activity begins and ends. But one significant instance of intentional activity occurred this past week.

One of the CNAs who is closest to my son Christopher reported last weekend that Christopher spoke to her late Saturday afternoon. The CNA was struggling emotionally, trying to hold back tears, as she was tending to my son. Something had happened that deeply pained her, while caring for another resident a few minutes earlier.

Christopher could sense something was wrong. He realized she was tearing up, though she was not crying audibly. He softly and clearly asked her, “Are you okay?”

I asked our family’s personal medical consultant, Dr. Robert Potter (M.D., Ph.D.), for his reflections on my report. Dr. Potter’s areas of specialization include palliative care and medical ethics. He indicated the fact that Christopher’s question was coherent, and appropriate to the context, signified intentionality. It was not an instance of automatism, where someone’s speech is coherent, but not contextual. The good doctor also shared, “Events like what you report are so important and give so much information about what is happening in the brain. Like all events, they have to be critically evaluated and not be over interpreted. This event to me means progress. What I cannot be certain of is how much progress, or what is the next step in the progress to watch for.”

My wife Mariko also reflected on what transpired. She shared with me that in spite of all the upheaval in Christopher’s brain due to the traumatic brain injury, he comprehends certain things. He feels this CNA’s compassionate care for him and responds in kind with compassion. It demonstrates that he is aware of his immediate context and can see (the eye doctor is not sure he can see). Again, the CNA was tearing up, though not crying audibly.

I added that with all that Christopher has gone through, he demonstrated the awareness and concern for someone else. Instead of fixating on his minimal state of wellbeing, he was concerned for another human. It reminded me of the time many months ago when he reached out his hand toward me when I broke down in tears at his bedside. I’m so proud of my son for his regard for others and their well-being. I hope to be just like him someday.

Christopher’s first reported words in months was not (fortunately) Will Ferrell’s line as “Chaz” in Wedding Crashers, “Hey Ma, can we get some meatloaf?!” or his line as “Ron Burgundy” in Anchorman, “I’m not quite sure how to put this, but… I’m kind of a big deal;” or his line as Ricky Bobby in Talladega Nights, “If you ain’t first, you’re last.” Christopher’s first reported words in months were “Are you okay?” That question’s not comical. Nor is it tragic, despite Christopher’s horrific ordeal. Those words lighten my spirit and fill my heart with hope. No matter the state of Christopher’s brain activity generally, his humanity involving consideration of another human’s wellbeing is intact. Now that’s human progress!

My son’s consideration of his compassionate and skillful caregiver who always considers what’s best for his wellbeing reminded me of Philippians 2:3-4: “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit, but in humility consider others better than yourselves. Each of you should look not only to your own interests, but also to the interests of others.” (Philippians 2:3-4; NIV) Later, in the same chapter, Paul writes of Timothy his son in the faith: “I have no one else like him, who will show genuine concern for your welfare. For everyone looks out for their own interests, not those of Jesus Christ.” (Philippians 2:20-21; NIV) If we all operated the way they did, we would have far fewer conflicts in the home, workplace, and society at large.

I sometimes despair of not demonstrating a genuine concern for Jesus Christ’s interests and those of others. At times, I wish such concern were automatic, involuntary. But if such concerns were involuntary, what real difference would it make to our humanity? Virtue involves intentionality and volition. It requires motivation from the heart. As imperfect as our humanity and care for one another is, I would rather we be human persons with fallible hearts and wills rather than unfeeling, error-free, preprogrammed automatons. As important as technological progress is, human progress entailing purposeful care for others’ well-being is even more important.

Christopher’s CNA manifests humane intentionality, volition, and motivation from the heart. She approaches Christopher compassionately, almost as if he were one of her own family members. For his part, Christopher senses that and demonstrates compassionate regard for her in turn, as his question conveyed the other day. Similary, Dr. Potter manifests compassionate regard for Christopher and us. He closed his email the other day to me with these words: “I remain available, and prayerfully engaged, always.” That was by no means automatic speech, by no means an out-of-office automated reply. It was both coherent and contextual. He was mindful of our situation and our need.

Like my son, Dr. Potter and Christopher’s CNA exercise healthy regard for others’ well-being. No matter our level of consciousness or emotional challenges, no matter our prognosis medically, or status societally, may you and I model authentic humanity. May we operate with purposeful activity, considering others better than ourselves.

I may be far more coherent than my son most days. But how contextual or appropriate is my speech to the various situations at hand? Do I make points and ask questions that are appropriate and fitting to people’s particular needs? If I were to speak only once in months, I can think of few things worth saying more to someone else than “Are you okay?”

It is easy to operate in a way that discounts purposeful, conscious activity and the need for examining our lives for how well we are living before God and others. Rather than operate in ways that might suggest non-purposeful activity, or activity that is purposeful but focused only on our own struggles and aspirations, may we be very alert and attentive to others’ wellbeing. May we ask not simply “Am I okay?”, but also, “Are you okay?” Regardless of how much progress we discern in every other area of our lives, and no matter how often or seldom we speak, such events convey that we are making human progress where it counts most.