This article includes two responses from Christian friends who take further the pressing issues addressed in this post.

This article includes two responses from Christian friends who take further the pressing issues addressed in this post.

***************

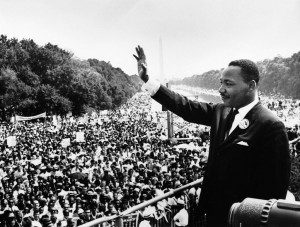

Over the years, I have noted criticisms Evangelicals make of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. My glowing praise and affirmation of King over the years has raised questions and criticisms, too. In my experience, Evangelicals have often been quick to point out King’s acts of infidelity and plagiarism in his doctoral work without attending to and celebrating sufficiently the incredible landmark achievements wrought by God through King. By no means should we sweep King’s flaws and sins under the carpet. Nor should we belittle or fail to recognize God’s profound work in the civil rights movement in and through this man.

For what it’s worth, I made note of King’s virtues and flaws in the book, Consuming Jesus: Beyond Race and Class Divisions in a Consumer Church. There I also drew attention to James Cone’s claim that King was/is America’s greatest theologian. See James Cone, “Martin, Malcolm, and Black Theology,” in The Future of Theology: Essays in Honor of Jürgen Moltmann, ed. Miroslav Volf, Thomas Kucharz, and Carmen Krieg (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), p. 189. For a discussion of King’s particular flaws, see Michael Eric Dyson, I May Not Get There with You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Touchstone, 2001); see also Richard Lischer’s discussion of King’s plagiarism problem in The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word that Moved America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 62-64.

One article I have written and posted on a few occasions has received criticism for what those respondents take to be a gloss on King’s faults and failures. I would encourage readers of that blog post titled “Unfinished Business” to note the context for my piece: the post is the substance of a public address given in honor of King on the eve of the day we remember his life and work. It was not the place or the time to discuss this great man’s sins and flaws. Still, it is the time to highlight how many white Evangelicals take note of Jonathan Edwards’ incredible intellectual achievements and work in spiritual renewal; however, we often fail to account for the troubling fact that he owned slaves. If we are quick to point out King’s flaws/sins, we should do the same with Edwards. Why don’t we? Why are we aware of King’s errors and faults, and not so aware of Edwards’s problems?

We Evangelicals also need to be more attentive to how we often blame the victim. Here I call to mind a striking conversation: an Evangelical criticized King for his lack of biblical orthodoxy in the presence of Dr. John M. Perkins. Interesting perhaps, the man in question and Perkins are both African Americans; however, they viewed King’s presumed lack of orthodoxy differently. Perkins responded by saying something to the effect that we should be very slow to blame King for his lack of conservative theology, when Bob Jones University would not have admitted him.

Moving on from the failure of those who would have refused King admittance, white Evangelicals are often quick to judge sins of commission (what people do wrong) while failing to account for sins of omission (what people fail to do). For example, Evangelicals were, by and large, absent from the civil rights movement and its protest marches, a point Perkins has noted and lamented. In the face of oppression, those who stood by silently were by no means innocent. Today, if we leave King’s work unfinished (the subject of my earlier blog post), we are by no means innocent.

Not only should we make every effort to complete King’s unfinished work, but also we should not compare ourselves favorably with King. Statements that relativize his achievements by stating that we all do much good and much bad, just like King, make me wonder how little we really get of how bad things were for him and his people. It also makes me wonder if we realize how great his/their triumphs over Jim Crow were. King went to an early grave facing down the horrors of a racist system that was bent on marginalizing and oppressing his people then and now. I don’t think I grasp anything close to the depth of the struggle he and his people faced and still face. I know of few people in the history of this country whom God has used as remarkably as King. In the midst of his flaws and sins, God used him far more than he has used most any of us or all of us.

I have no problem calling King a prophet of God as it pertains to the landmark work of the Civil Rights movement. Here I call to mind the stories I have read of King’s life and his sense of divine direction, clear vision and courage to face down incredibly large Pharaoh-like challenges in view of God’s sustaining grace with the call “Let my people go.” King David was a deeply flawed man with blood on his hands for killing Uriah and taking his wife for himself and harming long-term his household and the nation. Yet I doubt that many Christians in my circles would have any difficulty calling David a prophet of God. While we should not sweep under the carpet King’s or Edwards’ or King David’s sins, we should not let go but build on their prophetic work wherever possible; we have unfinished business to which we must attend. Specifically, as it pertains to King’s prophetic legacy, I need to ask myself, “What am I not doing today (sin{s} of omission) that continues to hold his people back from being all they can be?” All too often it is what we do not do that keeps people from doing all they can do to be all they can be.

***************

First Response by Clifford O. Chappell

As an African American pastor, I think it is highly commendable to acknowledge the life, legacy and work of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Yes, he may have had his flaws. Who doesn’t? But he also had a calling to which he obviously said YES unconditionally! I wonder what skeletons/sins would be revealed in the closets of those who choose to highlight his flaws and not his surpassing accomplishments, especially if their lives are as public as Dr. King’s. It is easy to criticize someone else when one’s own sins are hidden. Yes, there is still much “Unfinished Business.” The sins of omission would be to fail to recognize the depth and the magnitude of the work of Dr. King and to leave his work undone where he left it upon his death. To talk about and remember his dream is good, but it would be a travesty to drop it there. This would be a huge omission. But for all of us to carry forth his dream and to see racial and social equality and justice come to fruition in our world is to honor the great work of this great man.

***************

Second Response by Katrina Johnson

What is history, and who gets to decide how, when, and which parts of the story are told? This question is important because history is the narrative that shapes how we grow into our identity as a country, as socio-political groups, and as individuals. The ability to make decisions about how history is “told” and who is included have consequences for all members of a society. Prior to the mid 1900s in the West little was contributed to the narrative that did not participate in the the tacit agreement to maintain the privileged role of white males in American society. Voices that challenged this arrangement were generally not allowed to speak into the story. As a case in point, for my ancestors who were enslaved African-Americans, learning to read and write was illegal, and could carry a penalty of death. If a whimper or a cry escaped the pit to which opposing narratives were consigned it was concluded to originate from a perverse, inferior (whether morally or intellectually), and ultimately dangerous mind. We are furnished with stereotypes, or weaponized narratives, that blind us to the bitter-sweet complexity of the story.

When critiquing others’ engagement with this narrative, we must be careful to be charitable, especially where stories that give authentic voice to the existence of the “other” are concerned. This includes, but is not limited to asking ourselves whether or not we extend to them the same type and degree of welcome and productive critique that we offer those voices whose right to declare, pronounce, and expound, have traditionally been taken as a given. For example, we must ask why it has so often been seen as right and fitting to sacramentally pronounce Thomas Jefferson’s words “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal[1],” without constantly conjoining their recitation with a note on the author’s sexual practices with a woman he considered his property, and his other human rights violations as a slave holder. When we extol the ingenuity, thrift, and work ethic of Benjamin Franklin, we must ask ourselves why we do not also feel it our duty with every instance of praise to mention that he fathered a son out of wedlock, and lived with a common-law wife. We must ask ourselves, why the popular painting of George Washington praying at Valley Forge seldom, if ever, leads us to consider “what the image means, in light of the fact that Washington was a Master Freemason, and a slave holder?”

In place of unflattering question, we tend to glory in the moral fortitude and reverence these historic figures are accorded within the narrative. When we look at beatific pictures of John F. Kennedy, we must ask ourselves about the nature of his relationship with Marylyn Monroe, and consider the curious circumstances surrounding her death. We must also ponder why it is that any brief praise of Martin Luther King, Jr. draws fire from various quarters. What is the issue? Should nothing be said of his contributions to humanity? Why then does the hammer of offended moral sensibilities fall so often at the name of Martin Luther King, Jr.? For those of us who are followers of Christ, why do we turn away from acknowledging King’s prophetic gift of exhortation, when the Bible even records the moral failings of David, a man after God’s own heart?

The main question is simply this: is it incumbent upon me to mention the moral failings of Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, John F. Kennedy, or Benjamin Franklin, when I wish to celebrate their achievements? Perhaps the reason we would not hastily answer “yes,” is because we recognize that there should be room in the narrative to celebrate the accomplishments of these individuals, just as there must be room to critique them. However, to demand that both always be done simultaneously is not the right of any individual or segment of the population. This would be to claim sole ownership of the narrative, and with it the power to silence other voices that do not capitulate to our demands. If we really want the diversity we claim to celebrate, “let it not be in acts of eye-service as if you had but to please men (Ephesians 6:6, Weymouth Bible)” or to fill a quota. We must be willing to hear from the “other” without putting our fingers in our ears, and without using rhetorical techniques and selectively applied moral objections to silence their voices. We must be careful not to hold the narrative itself in bondage to our own world views, whether popular or outlying. In this way we allow for multiple aspects of the story not only of a nation, but of humankind in general, to be critiqued, questioned, and or celebrated.

As followers of Christ we must pray for discernment, and constantly call on the Holy Spirit to show us where we succeed and where we fail, as we seek to live together in peace (Romans 12:18), listen to one another (James 1:19-20), and “let our love be sincere” (Romans 12:9), as we are careful to reject what is evil, but equally careful to embrace what is good (Romans 12:10), bearing in mind that all human beings are a mixture of the two. Our hope lies in the fact that we are justified, not that we are perfect. For we should always remember Jesus is the God man who, born into humanity as a Jew, was willing to cross cultural and political lines to bring healing to a Roman centurion’s household (Luke 7:1-10).

Consider the apprehension that the centurion likely believed his invitation would engender. He was so aware of the cultural and political divide he was asking Jesus to cross that he “sent some elders of the Jews to him (Jesus), asking him to come and heal his servant. When they came to Jesus, they pleaded earnestly with him, ‘This man deserves to have you do this, because he loves our nation and has built our synagogue.’ ” (Luke 7:3-5 emphasis added). The Jewish elders testified that this Roman is different. They did not mention that he participated in and enforced a system that oppresses the Jewish people. Is this appropriate? Is it honest? Why; or, why not? I think the answer is in Jesus’ response. “…Jesus went with them” (Luke 7:6a). He went not to condemn the centurion, but to bring the blessing of life, a token of the Father’s love, to the centurion’s house. For it is Christ’s love, which, when allowed to do its reconciling work within our hearts removes the distinction between “Jew and Greek, bond and free, male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Let us strive to live in His image, as we welcome one another into the shared story of our lives and seek to be agents of love.