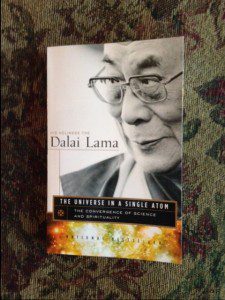

For all of orthodox Christianity’s differences in belief from the Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhism, we share many things in common. One of the things I admire most is his profound compassionate care for all of existence, most notably, his supreme regard for humanity. Such compassionate care is on full display in his volume, The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality (New York: Harmony Books, 2005). In his essay titled “Ethics and the New Genetics,” he addresses the need for a global ethic that attends to the discoveries in genetics.

For all of orthodox Christianity’s differences in belief from the Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhism, we share many things in common. One of the things I admire most is his profound compassionate care for all of existence, most notably, his supreme regard for humanity. Such compassionate care is on full display in his volume, The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality (New York: Harmony Books, 2005). In his essay titled “Ethics and the New Genetics,” he addresses the need for a global ethic that attends to the discoveries in genetics.

By no means does the Dalai Lama come across as a reactionary in his engagement of genetic research. However, in the midst of his affirmation of scientific progress that furthers the well-being of our planet, he cautions scientists, business leaders and politicians, even society at large, not to play God. This is quite noteworthy, given that Tibetan Buddhism hails the Dalai Lama as the rebirth of a line of enlightened beings who are appearances of Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. For the Dalai Lama’s own view of compassion, see his article “Compassion and the Individual.”

Here are some of the chapter highlights from “Ethics and the New Genetics”:

- Knowledge of genetic predispositions of disease may lead one to abort a child whose disease will manifest itself in twenty years; such knowledge of predisposition entails only a probability at best and does not account for the possibility that a cure may be found within ten years (page 191).

- The cloning or breeding of “semi-human beings for spare parts” makes it difficult to guard against exploiting “our fellow human beings whom the whims of society may deem deficient in some way” (page 192).

- The manipulation of genes for creating children with enhanced characteristic traits will lead us from “inequality of circumstance” to “inequality of nature”: given the costs involved with genetic technology, the rich over against those of limited means will be in the position for the foreseeable future to benefit from such technological opportunities to the detriment of the rest of society (page 194).

- There is so much more to human beings than their genetic codes. Regardless of whether or not one has a disability like Down syndrome or a genetic predisposition toward various diseases like “sickle-cell anemia, Hunting’s chorea, or Alzheimer’s,” “all human beings have an equal value and an equal potential for goodness. To ground our appreciation of the value of a human being on genetic makeup is bound to impoverish humanity, because there is so much more to human beings than their genomes” (page 195).

While the Dalai Lama tends to minimize various traditions’ religious beliefs in search of a global ethic (pages 197-198), I maintain that such differences can be constructive for the development of a global ethic. Surely, the adherents of various religious traditions should not approach ethics in a parochial and divisive manner that undercuts global partnerships. Still, we should bring even our differences to bear on ethical concerns so as to promote diverse strategies for addressing the various ethical quandaries we face.

For example, the Dalai Lama notes how from his Buddhist perspective it is difficult to justify people’s cloning of themselves in the attempt to live longer: “from the Buddhist perspective, it may be an identical body, but there will be two different consciousnesses. They will still die” (page 193). Certainly, we should not minimize, but maximize this point.

Moreover, it is important for various religious traditions to address ethical quandaries in ways where they might challenge one another in service to shared global ethical concerns. Perhaps Buddhists would challenge Christians and other theists with their beliefs in immortal souls. Intentionally or not, the Dalai Lama does indeed challenge theists of this orientation in his article on “Compassion and the Individual” noted earlier in this piece:

Let me emphasize that it is within your power, given patience and time, to develop this kind of compassion. Of course, our self-centeredness, our distinctive attachment to the feeling of an independent, self-existent �I�, works fundamentally to inhibit our compassion. Indeed, true compassion can be experienced only when this type of self-grasping is eliminated. But this does not mean that we cannot start and make progress now.

I affirm the need to move beyond a state of self-grasping, so to an extent, I agree with the Dalai Lama; however, I do not believe that belief in an immortal soul necessarily leads there; in fact, I maintain that such belief can move us beyond grasping in this life. The Lord Jesus argued that by taking seriously our eternal ensouled state we will move beyond grasping in this life. It is worth quoting his words at length as recorded in Luke’s Gospel:

“I tell you, my friends, do not fear those who kill the body, and after that have nothing more that they can do. But I will warn you whom to fear: fear him who, after he has killed, has authority to cast into hell. Yes, I tell you, fear him! Are not five sparrows sold for two pennies? And not one of them is forgotten before God. Why, even the hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear not; you are of more value than many sparrows.”

“And I tell you, everyone who acknowledges me before men, the Son of Man also will acknowledge before the angels of God, but the one who denies me before men will be denied before the angels of God. And everyone who speaks a word against the Son of Man will be forgiven, but the one who blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven. And when they bring you before the synagogues and the rulers and the authorities, do not be anxious about how you should defend yourself or what you should say, for the Holy Spirit will teach you in that very hour what you ought to say.”

Someone in the crowd said to him, “Teacher, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me.” But he said to him, “Man, who made me a judge or arbitrator over you?” And he said to them, “Take care, and be on your guard against all covetousness, for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of his possessions.” And he told them a parable, saying, “The land of a rich man produced plentifully, and he thought to himself, ‘What shall I do, for I have nowhere to store my crops?’ And he said, ‘I will do this: I will tear down my barns and build larger ones, and there I will store all my grain and my goods. And I will say to my soul, “Soul, you have ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.”’ But God said to him, ‘Fool! This night your soul is required of you, and the things you have prepared, whose will they be?’ So is the one who lays up treasure for himself and is not rich toward God.”

And he said to his disciples, “Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat, nor about your body, what you will put on. For life is more than food, and the body more than clothing. Consider the ravens: they neither sow nor reap, they have neither storehouse nor barn, and yet God feeds them. Of how much more value are you than the birds! And which of you by being anxious can add a single hour to his span of life? If then you are not able to do as small a thing as that, why are you anxious about the rest? Consider the lilies, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass, which is alive in the field today, and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, how much more will he clothe you, O you of little faith! And do not seek what you are to eat and what you are to drink, nor be worried. For all the nations of the world seek after these things, and your Father knows that you need them. Instead, seek his kingdom, and these things will be added to you.”

“Fear not, little flock, for tit is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom. Sell your possessions, and give to the needy. Provide yourselves with moneybags that do not grow old, with a treasure in the heavens that does not fail, where no thief approaches and no moth destroys. For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” (Luke 12:4-34; ESV).

Apart from dismissing that this text conveys Jesus’ voice, or distorting its meaning, one cannot help but see belief in an immortal God, heaven and hell, and eternal judgment of our souls as central to Jesus’ ethic. For Jesus, non-attachment to material possessions in view of our eternal state before God involving the soul’s permanence and judgment to come causes us to care compassionately for others, especially those in dire need. For what it is worth, Immanuel Kant also claimed that such notions as Divine Providence and the immortality of the soul are required as moral postulates of practical reason to safeguard morality/moral perfection (Refer here). Belief in these transcendent realities provides sufficient moral grounds for compassionate existence. Anything short of such convictions does not prove satisfactory, no matter how compassionate individuals and societies are.

The aim of these preceding points is not to undermine a collective global ethic. However, we must go through our various convictions in search of common ground, not go around them. By challenging one another, Buddhists, Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus and others can help strengthen our collective resolve and response to the challenges we face in search of a truly global ethic affirming all of life. As such, we become “trustworthy rivals,” as those of us at the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy maintain.

I thank God for the Dalai Lama, not because I agree with him at every turn. Rather, his profound insights into what is at stake for human life in the face of the “new genetics” are arguments from which Christians such as I can truly benefit. Moreover, we Christians need all the help we can get in the development of an ethic that is truly global and not tribal.