Glory and peace go together in Luke’s Gospel. Luke 2:14 states, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace among those with whom he is pleased!” (Luke 2:14; ESV) Paul Minear sees a direct connection between the glory and peace here: “The more glory the more peace, and the more peace the more glory.”[1]

It’s not any kind of glory and any kind of peace, though. So, how do we discern the signs of God’s glory and peace? For starters, Luke’s Gospel grounds the connection in Jesus. Elsewhere in Luke’s Gospel, the resurrected Jesus appears to his disciples and declares, “Peace to you” (Luke 24:36; ESV).

Before proceeding further, it is worth noting the fundamental connection between Luke 2 and the rest of the gospel. All too often, we take a biblical text out of its immediate context and apply it generally. Just as there is a fundamental connection between glory and peace, so there is a fundamental connection between the birth narrative and the whole of Luke’s Gospel: “The infancy narrative can be seen as a true introduction to some of the main themes of the Gospel proper, and no analysis of Lukan theology should neglect it.”[2] This should not come as too much of a surprise, since all four canonical gospels focus on the single life of Jesus. Thus, glory, peace, as well as joy will surface in relation to Jesus elsewhere (See Luke 10:20; 15:7, 10, 20-24; 24:36: Luke connects joy, peace and heaven with the gospel of Jesus’ kingdom).

All too often, people associate glory and peace with the peace of this or that empire, or nation state. But Jesus’ kingdom shalom looks very different. The Pax Christi is not the same as the Pax Romana or Pax Americana. Take the Pax Romana for example: Caesar Augustus envisioned a different gospel or “good news”: he saw Rome bringing peace to a violent world in which Rome was the world’s capital and the center of human destiny, and he used violence in the attempt to realize his vision. Jesus is born into this turbulent and violent world and under Roman rule at the time of Caesar Augustus’ census to register “all the world” (Luke 2:1). The tragic and striking irony could not be more pronounced. Caesar establishes his kingdom peace through violent power and control, and one of his subjects, Jesus, will establish his own kingdom through non-violence, weakness, and humble service (here it is worth noting Revelation 5’s throne room scene, where Jesus, who is the lion of the tribe of Judah and suffering lamb of sacrifice, reigns over all nations—a text that would have countered and challenged Caesar Domitian’s claim to total dominion).

Even today, people place their hopes in this or that empire or nation state. Christians should know better than to anoint this or that temporal ruler to establish heavenly peace, but still we often lean in this direction. With this point in mind, my friend Thomas John Hastings wrote a Christmas note to me in which he invokes Revelation 11:15:

I worry about and pray for those who claim God has anointed our president elect, just as I would worry and pray for those who came to a similar conclusion about his opponent. In coming days, we must be vigilant in clearly distinguishing real from fake in light of the evangel, for though things may not always be clear or self-evident in the flow of our historical present, there remains beneath, in, through and beyond it all the intelligible Faith, Hope, and Love who holds all things together (Col 1:17). God and God’s Christ are still God and never an idol of human imagining….

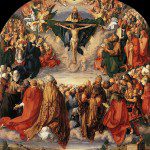

As Hastings states, “in coming days, we must be vigilant in clearly distinguishing real from fake in light of the evangel.” Human imagining will raise up idols that compete with God and his Christ, but will ultimately falter, just as Caesar’s reign came to an end. Not so with Jesus: “Then the seventh angel blew his trumpet, and there were loud voices in heaven, saying, ‘The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah, and he will reign forever and ever’” (Revelation 11:15).

As suggested above, this eschatological hope does not convey passivity in the current setting; vigilance is required to discern truth from falsehood and idolatry.

What might this mean for Evangelicals like me whose name is so tarnished today for political associations? We derive our name from the evangel—the good news or gospel of Jesus’ kingdom reign. But is that what the world around us associates with us? We must be vigilant to return to our gospel source.

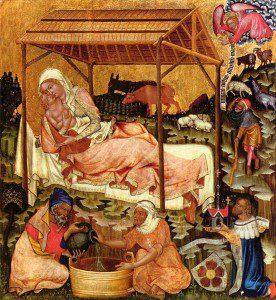

If we are true to the evangel as Evangelicals, it will require that we associate with the lowly rather than fixate on gaining power with the mighty. After all, God’s angels did not appear to the rulers, but to Zechariah, to Mary, and to the shepherds in Luke’s Gospel; and rather than compel them to fear, the angels encouraged them not to fear and to be comforted by their message—one of glorious hope and peace (Luke 1:13, 30; 2:10). The declaration to the shepherds that the Messiah was born (Luke 2:8-20) is significant here, for “the announcement of Jesus’ birth to the shepherds is in keeping with Luke’s theme that the lowly are singled out as the recipients of God’s favors and blessings” (see also Luke 1:48, 52; refer here for the source).

Shepherds care for their flocks. Is it such a stretch to think that all of us are to play some role in caring and shepherding the world, a creation in trauma? Moreover, rulers are to shepherd the people with care rather than bring about more pain and suffering. Yet all too often this is not how leaders lead. Shepherding is a theme that appears at various points in the New Testament, not simply Luke’s Gospel. As John’s Gospel reveals, Jesus is the Good Shepherd (See John 10; compare it with Ezekiel 34). In Matthew’s Gospel, we find Jesus teaching and proclaiming his kingdom, healing and caring for the people, and noting how harassed and helpless they were, like sheep without a shepherd. It leads Jesus and his followers to greater vigilance in prayer, proclamation of the evangel/gospel/glad tidings, and the demonstration of his kingdom’s reign of glorious peace. His kingdom is at hand (Matthew 9:35-38, Matthew 10).

Which evangel will we declare this Christmas season? Which Messiah figure will we anoint? Which glory and which peace will we celebrate?

_______________________________

[1]Paul Sevier Minear, To Heal and To Reveal: The Prophetic Vocation According to Luke (New York: Seabury, 1976), page 50.

[2]R.E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1979), page 242. See also Minear’s landmark discussion of this theme: “Luke’s Use of the Birth Stories, in Studies in Luke-Acts, ed. L.E. Keck and J.L. Martyn (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980), page 112.