|

| Flesh to fiber-optic interface from Battlestar Galactica |

Alex Knapp likes to kick around transhumanist problems at Forbes, and he’s concluded genetic engineering will almost certainly result in “horrific moral atrocities.” Simply put:

The “failed prototypes” are people. People who have to grow up and live with the consequences of the inevitable mistakes that will be made in the process of experimenting. Assuming, of course, they can physically live with those consequences at all.

And there’s the problem. When you get right down to it, I do not see any way to perform experiments involving signficant genetic enhancements that don’t end in the suffering of a human being. A human being whose DNA was altered without consent, who is participating in a scientific experiment without consent, and is, basically, being born into slavery, with their sole purpose in life being a stepping stone to making other people “better.”

I’m mostly in agreement with Knapp, so let me quickly get to where we diverge. I think he’s selling short the extent to which many fetuses, children, and adults end up in experiments they didn’t consent to that are meant for their own good. No fetus signed a waiver to be in a study of folic acid supplements, but they were hardly ‘born into slavery’ or reduced to a mere means as a result. And after birth, you can end up in a poorly run experiment, with potential for long term harm every time your state overhauls its school curriculum or changes the food safety standards. Let’s not inflate the threat-to-personhood danger just because these environmental changes are more cutting edge.

That being said, I’m in agreement that DNA-tweaking is dead on arrival. Genetic engineering is pretty much guaranteed to wind up in the middle of the abortion debate, since it’s a lot easier to select embryos than alter them. That issue taboos the whole subject for a significant proportion of the population. And pro-choicers like me still have plenty of reasons to be leery of the whole endeavor. As Knapp points out, any pre-birth enhancements tend to run into some serious problems with consent. We make plenty of choices that alter a baby’s biology, but this isn’t exactly folic acid supplements. There’s no strong consensus about what kind of enhancements are desirable or necessary, so there’s no way to argue that the person-to-be tacitly consents. And, historically, this kind of consensus isn’t all too trustworthy, anyway (cf. the practice of neo-natal genital surgery for intersex infants).

Absent a profound shift in expectations for our physical hardware, these objections are enough to kibosh any plan for human genetic engineering. And that’s fine by me, since there’s no reason transhumanists should have picked that as a goal to begin with. Focusing the conversation there is a way to push transhumanist goals into a far-distant future. Definitionally, you’re taking all the pressure off our generation, since, absent some really clever virus engineering, there’s no way we can use this tool to modify ourselves.

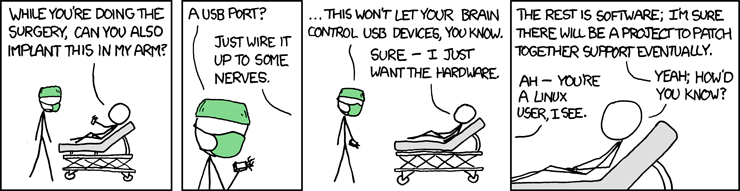

But aspiring body hackers do have options right now. The two I’m most interested in assimilating are a constant awareness of compass directions, and, subsequently, better navigational instincts, and the ability to sense electromagnetic fields (though I’d be going the magnets-in-nail-polish route, and steering clear of the surgical implants).

If those aren’t the augmentations you want, then start trying to put together a different mechanical/biological kludge. Just try and do some thinking about what you actually want to be, not what kind of thing is cool at parties. Levitation or flight sound cool, but I’m better served by the exertion of walking on a day-to-day basis, and when I do need to fly, I have this wacky trick called buying plane tickets.

Does that not seem cool and futuristic enough? Tough beans. Transhumanism is more about problem-solving than aesthetics, and plenty of currently existing tech can solve my problems even if it doesn’t meld with my wetware. But most people think that physical tech somehow doesn’t count and gadgets like my iPhone or my laptop (both of which radically change how I access, store, and process information, and then go on to give me totally new kinds of ways to act in the world) have nothing to do with the transhumanist project.

The weird thing is that even when we want to do something as radical as genetic engineering, we still want it to feel natural, smoothly and inextricably bound to us. An inborn sense of direction seems more real than training with the Northstar anklet. Farther along the spectrum, a surgical implant must be more a part of us than a magnet that’s only glued on.

One of my transhumanism hobbyhorses is trying to blur the definition of the body and stop privileging the squishy bits that happen to be attached to us at birth. Another one is making war on any infatuation with the ‘natural’ or ‘organic’ generally. I’ll worry about the aesthetics of an interface after I’ve got something I can use.

Oh, and don’t forget that some of the best bang for your buck transhumanism around is policing cruft and biases in your own reasoning. Cognitive hacking is still hacking, even if it doesn’t get to incorporate any cool-looking LEDs.