Helen Rittelmeyer is blogging and writing again. She just contributed to the American Spectator’s Youth Symposium, claiming that relativism is no longer conservatism’s greatest enemy. Let me grab a pull quote.

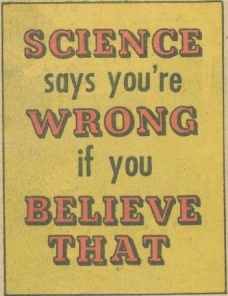

In the last culture war, relativism’s influence was evident in the stock arguments that kept appearing in magazines and op-ed pages: Breaking taboos is valuable for its own sake; people have a right to make their own choices and not be judged for it; what you call a social evil is really just a cultural difference; et cetera.But those articles are no longer seen so often. Now, the most annoyingly ubiquitous genre in journalism is the social-scientific analysis, as if a person can’t speak with authority without citing economics or sociology.This is bad enough in political conversation, but it has begun to affect people’s ethical thinking. Under the new cultural rules, moral condemnation is a legitimate thing to express, but only if you can demonstrate that the sin you want to condemn makes someone twice as likely to take antidepressants or 40 percent less likely to be promoted at work. Malcolm Gladwell and the Freakonomics guys have more moral authority than the archbishop of New York. Great artists are producing movies, TV shows, and songs about tough moral dilemmas, but although liberals buy the tickets and the albums, they don’t take the art they consume very seriously. When moral questions arise, they forget The Wire and The Hold Steady and ask what the studies show.

An excellently ludicrous example of this mindset was offered by an article on weight loss I read earlier this summer. It opened by citing a handful of studies showing obesity to be correlated not just with heart disease but also with slower career advancement and a greater likelihood of developing mental-health problems. Let’s leave aside the fact that the author didn’t feel he could take the undesirability of being fat as a given. The bigger problem is that this sort of argument tries to have it both ways—to have all the benefits of authority without the burden of being answerable to people who disagree. On one hand, the author isn’t saying obesity is bad, science is, which makes it a fact and not an opinion. Your personal experience or common sense might tell you that a few extra pounds aren’t always such a disaster; but that just means you’re in the statistical minority for whom these bad outcomes do not eventuate. In other words: My moral claim is objectively correct, but that doesn’t mean it has to be true in your case. The same evasive maneuver can be seen in the argument that there’s nothing wrong with pornography because its prevalence isn’t correlated with higher crime rates, or that there’s nothing wrong with gay marriage as long as children of same-sex couples aren’t more likely to receive reduced-price lunches at school. The idea that something might be spiritually harmful (or beneficial) in a way that can’t be demonstrated statistically has been written out of the conversation.

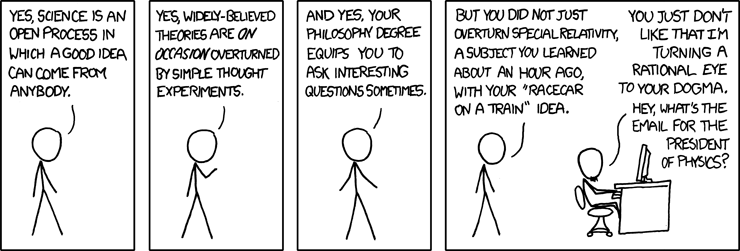

Helen brings up the true-in-aggregate characteristic of these studies as a barrier to challenges or questions. I’ve used the line “The plural of anecdote is not data” often enough that I can’t help but feel like she’s talking about me. A lot of the time, it’s a pretty good defense, especially in the public health debates where I tend to use it. When it comes to herd immunity, taking your full course of antibiotic even though you already feel better, or anything else where your actions have a big aggregate impact — almost everyone who thinks they’re an exception to the rule is wrong.

But as long as people don’t understand why they’re being asked to do counter-intuitive things (or, more precisely, why their intuitions are wrong), epidemiologists are going to come off as techno-mystics. When we intone “Lo it is written that the findings were significant at p=.05 in an SRS sample. Let he who denies it be anathema!” it might as well be Latin. (And poorly catechized scientists sometimes treat statistics like magic and introduce a host of errors, but that’s another rant).

For people who aren’t fluent in social science, the growing authority of the studies may not foster relativism, but it does promote an unhealthy agnosticism. It’s natural and delightful to be fascinated by the way things work, and the more distant the data is from every day experience, the more frustrated or fearful you may become in your explorations.

I’m speculating. As a data nerd, I obviously know the other side of the equation a lot better, so let me talk a little about the perils for the savvy. I was a political science major, and when I didn’t quite have time to finish the reading, I knew the quickest way to prepare something to say for class was to just read the methodology of a paper intensively. Spot a flaw or notice a way that the results are hard to generalize (besides the standard WEIRD reason) and you’ve got your comment. This is a useful skill, but it’s a kind of strange habit to cultivate.

The kind of people who get the kind of stat education I have are usually pretty good at analyzing a system and figuring out a way to game it (or at least move through it efficiently). So if I’m not figuring out a plausible reason why a study doesn’t apply to me, I might be figuring out a different way to buy the benefit described. Maybe I can trade keeping a gratitude journal for getting a pet. I still haven’t done the math on how much exercise I can skip in exchange for eating really dark chocolate.

But if I’m talking about virtue, I can’t really do offsets. I can’t be a jerk to my brother and then balance the books by spending some time at a soup kitchen. There’s no way to game goodness the way you can hack happiness.