In C.S. Lewis’s Of Other Worlds, most of the selections in the book are critical essays, but there a few pieces of fiction included, one of which is a never completed novel that C.S. Lewis meant to write about Menelaus and Helen during and after the Trojan War. In the excerpt below, Menelaus stops fantasizing about torturing Helen if he regains her.

[H]e wouldn’t torture her. He saw that was nonsense. Torture was all very well for getting information; it was no real use for revenge. All people under torture have the same face and make the same noise. You lose the person you hated.

I was struck by this passage, since frequently discussions of torture (fictional and nonfictional) treat it as revelatory. In Firefly‘s “War Stories” Shepherd Book quotes Shan Yu — a fictional warrior whose philosophy informs the actions of that episode’s antagonist.

[Shan Yu] fancied himself quite the warrior poet. Wrote volumes on war, torture, the limits of human endurance. [He wrote] “Live with a man 40 years. Share his house, his meals. Speak on every subject. Then tie him up, and hold him over the volcano’s edge. And on that day, you will finally meet the man.”

The idea that we are most ourselves under stress is prevalent. Hurt someone badly enough, and every decent drapery will be stripped away, and you’ll meet the authentic self they tried to mask. See also “It has been said that civilization is twenty-four hours and two meals away from barbarism” (from Good Omens) and the idea that wine and wrath lower inhibitions and reveal identity. All of this presupposes that anything we do by effort can’t be authentic, when I’d argue that our choice of mask and drapery is the best indication of our character. It’s quite hard to successfully dress up as Christ, but surely there’s something to be said for our choice of what we’d like to be, if we were strong enough.

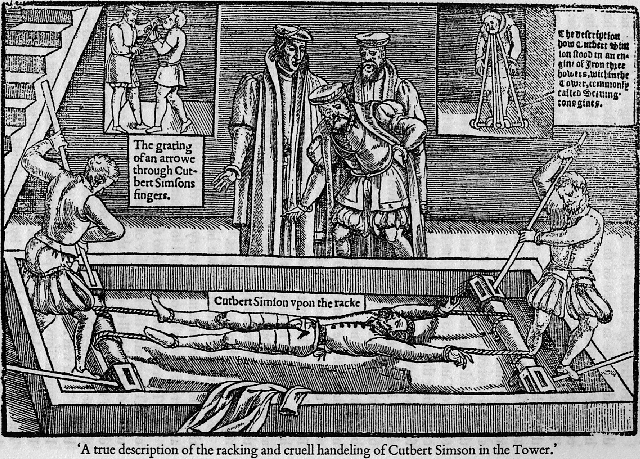

So, people who think torture is dehumanizing tend to focus on the experience of the person being tortured. You can experience and flinch from pain without higher reasoning functions. The torturer isn’t so much interacting with anything that makes you you, just the base functions that make you a living creature — the need to breath, eat, sleep. What I find interesting about Lewis’s quote is the way he assumes torture takes a toll on the torturer.

It would cost Menelaus something to try to interact with a tortured Helen. If he persuaded himself to accept the generic person-in-pain as his wife, it would impoverish his understanding of what a wife was or what a human is. Someone who uses an inflatable sex doll is better off not trying to convince himself that he’s experiencing the fullness of intercourse, or physical stimulation is all he’ll expect from or ask for when he has a living, thinking partner.

The person being tortured is being treated as inhuman, without regard for human dignity or the particular beauties and wonders of being human. But if the torturer thinks he can achieve satisfaction by lowering himself and his victim, he is assaulting not only his victim’s humanity but his own idea of humanity, and he will carry that self-inflicted wound with him when he leaves the chamber.

Lewis’s Menelaus saves himself and Helen by recognizing that torture destroys the proper relationship between humans. And if he wants to be able to repair his bond or sunder it or just ask Helen for an explanation of why she did such violence to their vows, he needs to act within the relationship they share and the fullness of their identity of Menelaus and Helen, husband and wife, two humans — both alike in dignity.