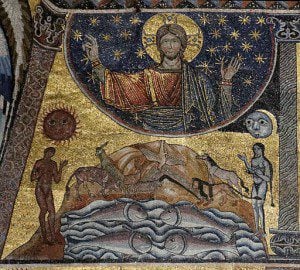

God brought a world into being, and thereby became vulnerable, instilling within creation a measure of freedom for its own continued development. Gen 1 suggests that God’s spoken, creative word entrusts creation itself with the glorious responsibility of freedom. God sanctions its self-emergence: “let the  water…be gathered…”; “let the land produce vegetation;” “let there be lights in the vault of the sky”; “let the water teem with living creatures”; “let the land produce living creatures.” Throughout Gen. 1-3, creation is not represented as a finished, final product. As Terrence Fretheim notes, “at the divine initiative, the creation plays an active role in God’s creating work”[1]. When God rested on day seven, creation charged on. William Brown paints the image of God as priest over creation: Resting on the sixth day, he entrusted “to humanity the power and responsibility of managing creation” [2].

water…be gathered…”; “let the land produce vegetation;” “let there be lights in the vault of the sky”; “let the water teem with living creatures”; “let the land produce living creatures.” Throughout Gen. 1-3, creation is not represented as a finished, final product. As Terrence Fretheim notes, “at the divine initiative, the creation plays an active role in God’s creating work”[1]. When God rested on day seven, creation charged on. William Brown paints the image of God as priest over creation: Resting on the sixth day, he entrusted “to humanity the power and responsibility of managing creation” [2].

God’s sovereignty includes self-imposed limitations, which means creation is both dependent (on God) and contingent–but free. God initiates a largely “free process” (Polkinghorne) which involves creation in an ongoing dynamic of development and change. While creation is relatively free, it is not autonomous of divine influence. As Ian McFarland notes, the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo was meant to secure the distinction of all created matter from the Creator. Creation was affirmed to be dependent on God as its sole cause and to be subservient to God’s will. God alone was cause of its origination.

Creation is ‘very good’ but not perfect.

Creation is neither complete, harmless, nor tame. In creation God through the Spirit, word and wisdom brings order to disorder and beauty from chaos, but neither pain, suffering nor danger are excluded from what God calls “good.” Douglas John Hall, in God and Human Suffering, suggests the creation narrative makes room for constructive forms of suffering: loneliness, limits, temptation and anxiety. This is because “struggle is necessary to the human glory that is God’s intention for us” [3]. The desire to provide an answer to the problem of evil and suffering sometimes tempts Christians to want to read Genesis 1-3 as laying the blame for natural suffering (and death) on original human sin. In so doing, we ironically elevate the role of humanity’s burden for what happens in creation to a height (or depth) the Scriptures do not demand. We are also tempted to trace the origin of all contemporary natural suffering to human sin (whether current or ancient). Genesis 1-3, however, suggests that natural disasters are part and parcel of a dangerous but beautiful world. The recognition that creation is “very good,” but not complete, provides motivation for human involvement in the preservation, cultivation and ongoing care of the earth.

We Are “Red Earth Creatures,” but in the Image of God

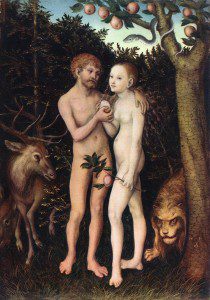

Human beings play a prominent role in both creation accounts. In Gen 1, they are the culmination of God’s creation; in Gen 2 the human (adam) is not only the first of animate things created, but, along with the woman, Eve (“mother of all living”), is the central character in the narrative. The “image of God,” presented in Gen 1 is given legs in Gen 2. The adam, or “groundling” (this literally could be “red earth creature”) is enlivened, animated by the breath of God. So the human being is created through a synthesis of divine breath and mud. This red-earth creature, which we are, is also given the responsibility to care for the earth–to be God’s “image-bearers” in the world and to cultivate, or care for, the earth. See Benjamin Corey’s excellent blog post for the implications of this responsibility. And by the way, I think imago Dei, or “image of God,” has more to do with our vocation as “cultivators” than it has to do with any substantive capacity (like rationality).

Human beings play a prominent role in both creation accounts. In Gen 1, they are the culmination of God’s creation; in Gen 2 the human (adam) is not only the first of animate things created, but, along with the woman, Eve (“mother of all living”), is the central character in the narrative. The “image of God,” presented in Gen 1 is given legs in Gen 2. The adam, or “groundling” (this literally could be “red earth creature”) is enlivened, animated by the breath of God. So the human being is created through a synthesis of divine breath and mud. This red-earth creature, which we are, is also given the responsibility to care for the earth–to be God’s “image-bearers” in the world and to cultivate, or care for, the earth. See Benjamin Corey’s excellent blog post for the implications of this responsibility. And by the way, I think imago Dei, or “image of God,” has more to do with our vocation as “cultivators” than it has to do with any substantive capacity (like rationality).

Creation is fallen, but will be perfected.

The biblical narrative is book-ended by the tree of life: its subtle (and often overlooked) presence in the center of the Garden of Eden and its more prominent place in the eschatological vision of the book of Revelation suggests that as creation continues on, in all its fertility, mystery, wonder and tragedy, so does God’s redemptive plan for history and for creation. God has invited into that project people who, following in the way of Jesus Christ and in the power of the Spirit, embody and reflect God’s image in the world. They seek to witness to and extend the gift of God’s grace throughout creation as God initiates its consummation, synthesizing earthly reality with the Kingdom of God. The New Jerusalem will descend and make right, heal and complete the old order of things. But this gives us no right to treat the earth and its resources instrumentally or flippantly. What is happening to the earth and its atmosphere and climate is frightening. We must–and can–do better. But we shouldn’t put our ultimate hope in the earth’s condition either–or certainly in our own capacities to preserve it or to heal it.

[1] Terrence Fretheim “Genesis and Ecology,” in The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation, p. 685.

[2] William P. Brown, The Seven Pillars of Creation, p. 46.

[3] Douglas John Hall, God and Human Suffering, p. 62.