I have decided to write a series of posts in which I explain my own theological journey through evangelicalism–and outside the other side. I have contemplated doing this for some time, and now with the end of my first year teaching behind me (at an ecumenical seminary decidedly not identified with evangelicalism), I feel a bit freed up to think about my journey more reflectively. It’s a hot topic too, thanks to the release of Rachel Held Evan’s book, Searching for Sunday, and the discussion her journey to the Episcopal church has provoked regarding the identity of evangelicalism and its future viability for the increasing ranks of the malcontent. (Note: RHE has pointed out her book is not really about evangelicalism and its problems, but that’s how the conversation has turned).

I’m not taking this on because I think people need to hear the specifics of my personal journey, but because it seems there are quite a few people out there with similar stories and similar questions, who are wrestling with their own theological and faith-identities. Perhaps these posts can add to an already vibrant discussion about what it means to be Christian today–in particular, what it means to be “evangelical.” For many of us, it is becoming increasingly difficult to own the term. When does the old wineskin break?

The problem with this discussion is that, first of all, “evangelical” is a deeply contested term. Kimlyn Bender gives a good short definition: a “post-World War II phenomenon with roots in American Puritanism, Pietism, and revivalism”[1]. Twentieth-century evangelicalism, sometimes called “neo-Evangelicalism,” began as a more culturally and intellectually-savvy advance upon its more awkward brother, Fundamentalism. This historical context is supplemented by consideration of its theological values. David Bebbington’s influential summary of evangelicalism highlights these four emphases: (1) Biblicism (authority of Scripture); (2) conversionism (importance of personal repentance and faith in Christ); (3) crucicentrism (the centrality of the cross in Christian life and church practice); and (4) activism (working out faith in good deeds and evangelistic practice).

These conceptual definitions take a back see to the real-life instantiations of evangelicalism: the  institutions which self-identify as evangelical (colleges and seminaries, publishing houses, churches, para-churches, celebrity pastors and ministry leaders, etc.) are the actual ideological centers where the real boundaries of evangelicalism are policed and determined. And on the other side, the popular media and populist perception of evangelicals is deeply determinative of what counts as evangelical.

institutions which self-identify as evangelical (colleges and seminaries, publishing houses, churches, para-churches, celebrity pastors and ministry leaders, etc.) are the actual ideological centers where the real boundaries of evangelicalism are policed and determined. And on the other side, the popular media and populist perception of evangelicals is deeply determinative of what counts as evangelical.

I have many friends and former colleagues who are fastidiously and sincerely working within the institutional pressures/constraints of evangelicalism, pushing for a broader, more permeable, more flexible definition of evangelical and evangelicalism. They are going back to the “roots” of evangelicalism, for some all the way back to European Pietism or to its nineteenth-century expressions in Wesleyanism. Their work is laudable and noteworthy. There are self-defined evangelical theologians, activists, pastors, para-church leaders, etc., who have mounted creative and visionary attempts to reshape and refine evangelicalism towards a more viable, more just, and more world-affirming future. Admittedly, were I still teaching in an evangelical seminary, my project would have continued to include elements of evangelical-renewal.

But it had become increasingly clear to me over the years participating in and observing evangelical settings that there is something about the self-identifying institutions of evangelicalism that mitigates against these efforts. Re-visioning efforts are painstaking and are often marginalized–either explicitly or implicitly–by an array of factors and pressures.

While much more could be said about the nature of the institutions–and their politics–that shape evangelical identity, I will focus my series on the theological points that seem to lie at the fulcrum of the contested tension between conservation of the tradition and openness to the new. These were the theological (and epistemological) points where I experienced most increasing discomfort with evangelicalism–and which have ultimately led me to embrace a “post-evangelical” identity.

(1) Theological Certainty: Evangelicalism, in my experience, has a deep internal reliance upon epistemic and theological certainty. Many evangelicals want, in Francis Schaeffer’s words, “true truth.

We could trace this longing to modernist, foundationalist epistemology and we’ve seen it illustrated in the reactivity by many evangelical theologians to post-modern (and post-foundationalist) epistemologies. It’s also intricately related to (many) evangelicals’ insistence upon the doctrine of biblical inerrancy. I develop this argument at length in Emerging Prophet: Kierkegaard and the Postmodern People of God.

(2) Biblical Inerrancy: Of its distinctive convictions, evangelicalism (but especially Neo-evangelicalism), is probably best known for this one. There are nearly as many shades of inerrancy as there are evangelical theologians, but it has remained an evangelical shibboleth that has created far more problems than it has solved.

(3) Eternal Judgment in Hell: We could also call this “eschatological exclusivism.” Many evangelicals lash out in fury anyone (see Rob Bell) who questions the doctrine of hell as “eternal, conscious, punishment” for any who do not accept Jesus as “personal, Lord and Savior” in this life. Could it be that, if there is a Hell for the purposes of judgment, it might be empty one day?

(4) The Gospel as “Penal Substitution”: What is the “good news”? For many evangelicals, the gospel is defined nearly exclusively as the “substitution” of Christ’s righteousness for the guilt of sinners. This definition is dominated by the economic metaphor of exchange/transfer/paymenet and is thought of as an “objective” change (in God’s mind) with subjective results. But what if the Gospel is, by definition, much more than what can be enclosed in a single atonement theory?

(5) Patriarchalism and Sexism: There are numerous evangelical egalitarians who affirm the full equality, giftings, and capacities of women in ministry leadership, but I have seen too much patriarchalism, or “complementarianism,” (and have observed its harmful effects) to leave this one off the list.

(6) Heteronormativity: A good bit of the retrenchment I have observed in evangelicalism seems to be a direct response to the ideological and theological challenges raised by the cultural movement toward marriage equality and the full inclusion of LGBTQ persons in the church. There are changes happening, as major evangelical theologians and prominent churches are shifting toward inclusion, but the virulent resistance by many evangelicals to these changes marks a clear point of tension.

(7) Science and Human Origins: American evangelicals seem to be the last hold-outs when it comes to accepting the scientific consensus regarding the age of the earth/universe and of biological human origins. This is understandable, since to accept evolution requires some serious rethinking of inherited theological assumptions. This serious thinking is happening in many evangelical circles. But the resistance/retrenchment is happening, too.

There’s more I could deal with (and I might as the series moves along–I’ll take suggestions!). And there are also many good things to say about evangelicalism. Evangelicals have been–and continue to be–among the leaders in many social justice movements today. Their commitment to Jesus Christ and to the Word of God has inspired moral courage and great sacrifice on behalf of others. The centrality of “gospel” is something all Christian traditions need to be recalled to (although “gospel” is variously defined). And the missional movement within evangelicalism offers great potential for reconfiguring its witness in the world and for seasoning other Christian traditions.

Despite how it might sound, I am very grateful to my evangelical heritage and even to the theological tradition in which I have been formed. However–and of course I am not alone–these stated points of tension have ultimately led me to accept that my theological trajectory has put me on a new course. Perhaps American Christianity is, in fact, experiencing what Phyllis Tickle called a “Great Rummage Sale” and a new thing is being created in our day. If so, I’m ready to figure out what that new things is.

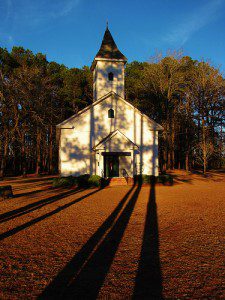

photo credit: <a href=”http://www.flickr.com/photos/11629603@N04/11559523773″>Centenary Memorial United Methodist Church (2)</a> via <a href=”http://photopin.com”>photopin</a> <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/”>(license)</a>