I appreciate Scot McKnight taking the time to engage my recent post on inerrancy (See his response here. Se my inerrancy post here). He largely agrees with my critique of the term “inerrancy” and the way it is often used in Evangelical settings. But he asks a good question:

If all we do is poke holes in inerrancy, and acknowledge the Bible’s problems, then we may only feed the flames of doubt and contribute to a environment of skepticism and distrust toward the Bible as Scripture  (sacred) and as Word of God. Many young Christians–and even seminary students, no less–are already struggling with the problems they see in the text. Do we really need to fan those flames? Or, as McKnight is more positively saying, what can we do to situate our discussion of the Bible in the context of a hermeneutic of trust, rather than a hermeneutic of suspicion?

(sacred) and as Word of God. Many young Christians–and even seminary students, no less–are already struggling with the problems they see in the text. Do we really need to fan those flames? Or, as McKnight is more positively saying, what can we do to situate our discussion of the Bible in the context of a hermeneutic of trust, rather than a hermeneutic of suspicion?

Here is McKnight’s challenge, in his words:

So, I sympathize but I want more at the end (and perhaps Kyle will provide that) — and I want to see those problems set in a hermeneutical approach that encourages us to trust that God speaks to us in Scripture. In other words, I want the more of a constructive approach to Scripture that can be used by churches and individual Christians.

By way of response, let me suggest a few metaphors that I think help us move toward a “constructive approach to Scripture”

(1) The “Fifth Act.” In his discussion of biblical authority, N.T. Wright offers the metaphor of the Bible as a five-act Shakespeare play (but the fifth act has been lost). If a drama troupe only possesses four acts, they need to improvise the fifth. The first four acts function as an authority for the actors as they perform the fifth. Same with Christians using the Bible today. If you go with this analogy, the doctrine of inerrancy seems rather out of place. Yes, the biblical text is the primary authoritative source (“actors” should respect its plot-line, character development, and so on), but they must move beyond it if they are going to be faithful to it. Getting lost in the weeds of concerns about inerrancy will only bog the actors down, stifle creativity, and divert the actors from moving forward. As Wright points out, the Bible only has authority because of God–not the other way around. Sometimes we read the Bible as if God gets authority from the Bible, when the truth is the converse. We can respect the Bible as as our sacred text, and as our “originary covenant document” (Wright), but let’s not ask it to do more (or less) than it is meant to do. And, let’s not be afraid to move beyond it when necessary. And let’s remember that God is the real authority, not the text.

(2) A Library, with the gospels at the center. Brian McLaren popularized the metaphor of the Bible as a library of diverse documents, rather than as a single, unitary “book” (which Gutenberg made possible). Let’s see the Bible as a polyphony of voices, a symphony of instruments, and then a library of fascinating texts, written, edited, and redacted over thousands of years, containing diverse messages, viewpoints, and yes, even a plurality of theologies. But with that diversity, Christians can also see the gospels themselves as standing out at the center, calling out for special attention. In this sense, I am quite OK acknowledging a “canon within a canon,” with Christ (the image of the invisible God) primarily determining our understanding of God and God’s relation to us. When you accept the diversity of Scripture and the “library” of the canon, you allow for the depth dimensions of the Bible and you explicit reject the “flattening” of the Bible onto a single plane of meaning. You will no longer read the “problem texts” in the OT (rape, genocide, etc.) the same way that you read the meaning of the kingdom of God in the synoptics, or the love of God in John, or the gospel of reconciliation in Paul, or the imperative of justice in the minor prophets, or the eschatological vision of the new creation in Isaiah, etc.

(3) A Sacrament. William Abraham has suggested that the Bible be understood as one of a number of “sacraments” that comprise the instruments of Christian devotion, worship, and theology. This is an intriguing prospect and one that I have not spent much time with. But what if we approached the Bible in Christian communities as a “window” to the divine, an opportunity to glimpse the reality of God through the “stuff” of creation? Historically speaking, the Bible’s composition as a collection of documents stamped with authority is not unlike the way other sacraments evolved into liturgical use in Christian tradition. The pietists admirably worked to take the Bible back from the creedalists and reclaim its place as an instrument of worship (piety, devotion) and as facilitating sanctification and spiritual formation. Thinking of the Bible in this sacramental way puts in the (positive) hermeneutical context of its function as sanctifying us in the truth. Let’s remember, the text so commonly used as a proof-text for the “doctrine of inerrancy” is really about the Bible’s sacramental, salvific, and sanctifying function:

All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, so that the servant of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work. (2 Timothy 3:16-17).

(4) A Love Letter. To stay with the pietist theme, Kierkegaard, who was deeply influenced by the Danish Moravaian pietists, used the metaphor of the Bible as a “love letter.” How do you read a love letter? You read is as a message from your beloved, and you read it with love in your heart and with a desire to act on it. You don’t treat a love letter as an “objective” document and parse every verb (or first write a commentary about it). Kierkegaard also followed the “library” approach to the Bible, reading it through the lens of the gospels as priority, then the Epistles, and so on. This prioritizing approach is what makes the “love letter” metaphor work. For more on Kierkegaard and the Bible, see my relevant chapter in Emerging Prophet.

(5) Believing Criticism. In God’s Word in Human Words, Kenneth Sparks, an Evangelical biblical scholar, uses this phrase to describe his constructive approach to Scripture. He argues that, contrary the common Evangelical disdain or fear of higher critical interpretive methods, that we need to read the Bible looking for what it actually has to say–and using critical tools and methods to do so–rather than imposing either the modernist anxieties of much of Evangelical inerrancy or a mere hermeneutical skepticism that discounts the Bible as Word of God. Sparks says that “believing criticism provides a different and better theological path, which steers clear of the problems created by traditional fundamentalism on the one hand and by secular biblical criticism on the other. The importance of my project rests in its attempt to assimilate the useful methods and reasonably assured results of biblical criticism to a healthy Christian faith.”

There are other metaphors or descriptors that could work in thinking through a constructive approach to Scripture (I welcome any other suggestions–by readers or by Scot McKnight himself!). I affirm the divine inspiration of the Bible, and marvel at its power to continue to speak words of life. It is the primary sacred text for Christians, and it is–I believe–the Word of God in written form. But it is not the only Word of God nor it is even the primary Word of God. That role is reserved for the Word of God,Jesus Christ.

We are being immersed now in conversation about Millennials leaving Christianity, the “rise of the nones” (who are now very much risen!). Christianity needs better ways to deal with the hard questions raised by the problems of the Bible, while moving forward in constructive ways conducive to a deeper, more integrated faith. McKnight’s concern and question is spot-on.

A final side note : I have long felt the tension between deconstruction and reconstruction, or between critical theology and constructive theology. In my own teaching, I’ve been surprised at what sometimes experienced by students as deconstructive or critical and what is sometimes experienced as reconstructive or constructive. As a theology professor, I have to admit that I feel I have very little control over when I “deconstruct” and when I “reconstruct,” with respect to my students’ faith. I’ve known professors who are so afraid that they are going to fan the flames of doubt, that they intentionally avoid difficult discussions in the classroom. But I’ve heard students testify complain that the avoidance approach is not particularly…well…constructive.

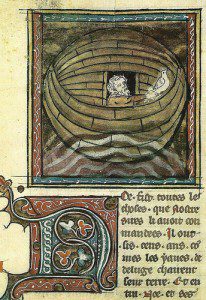

photo credit: <a href=”http://www.flickr.com/photos/127649572@N08/17047406749″>From the Bodleian Library Oxford. Miniature from a manuscript of the Bible historiale of Guiart des Moulins, 14th century.</a> via <a href=”http://photopin.com”>photopin</a> <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/”>(license)</a>