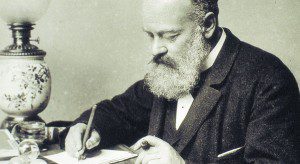

This post is a contribution to a Patheos Book Club discussion on Everyone Belongs to God, by the German pastor Christoph Friedrich Blumhardt (1842-1919). The book is a new edition of a collection of letters Blumhardt wrote to his son-in-law, Richard Wilhelm, who worked as a missionary pastor in China. For this post, I interviewed my friend and former colleague Christian T. Collins Winn (PhD, Drew University), who is Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at Bethel University, St. Paul, MN. Collins, among other things, is a Blumhardt scholar. His full bio and links to his author pages is below.

1. What drew you into studying Blumhardt? Was there something specific in these letters that exemplifies what you found (or find currently) important about this thought?

important themes that have touched me in a very personal way, shaping my understanding of the Christian life and of the gospel of God’s reign.

The letters between Blumhardt and Richard Wilhelm are a great expression of Blumhardt’s ability to think outside the normal lines of thought for the purpose of trying to discern where God’s Spirit is at work in the world. Blumhard’ts reflections on missions are remarkably far-sighted, given that they were written at the turn of the century. They include a profound critique of the colonial/imperialist agenda of the European powers and the attendant confusion of the relationship between Christian mission and Europeanization. At the same time, even though Blumhardt spurns the language of “missionary,” he retains a commitment to mission. However, it is the mission of God’s kingdom as opposed to the mission of Christianity, or Christianities. The former is about God’s work, the latter is about the confused work of ideological replication that Blumhardt found repulsive. Rather than pursue mission in this way, he believed the call of the Christian was to discern where God was already at work amongst the people, to come along side that work, and to cultivate and witness to God’s work such that Jesus would be able to emerge from within any given setting (in the case of the letters it is particularly Confucianism and Buddhism, and Chinese culture more broadly). I think this is not only relevant for today, but vital to our understanding and practice of mission.

certain polarities and problems. First, there was a tendency to separate church and mission. Church was internal, mission was external. Church was essence, mission was existence. Church was being, mission was act. In this situation, mission is understood as something that flows out of church, rather being understood as the very essence of the church-community, a community that is to be shaped according to the logic of the “sent One” or great apostle, Jesus. Thus mission was almost always external to the body-politic; mission was almost always “foreign” mission. Secondly, in these “foreign” settings, the mission of the church was almost impossible to distinguish from the mission of the colonizing powers, even though, we know now that many, many missionaries fought against this confusion. I think in some ways that Blumhardt was trying to pick at both of these problems, though much more the latter.

In regards to the former issue, I think Blumhardt had an inkling of the problem and believed that the essence of the church was mission, while also believing that the church itself was a mission field. Most of his ecclesiological reflections are decidedly critical, and move in the direction of arguing for a form of community existence that would be pliable to the ad hoc working of the Spirit in the world. (At one point in the letters Blumhardt even advocates a moratorium on baptism!). Unfortunately he didn’t offer enough on exactly how all of this would work itself out, and so his thoughts on the relationship between church and mission remain somewhat inchoate. He does, however, have quite a bit to say about the latter problem–the confusion of the gospel with European culture. His emphasis on the distinction between church and kingdom was a reminder that God cannot be domesticated in the forms of human religion, even the forms of the church, much less the state. There is thus a strong idolatry and ideology critique at play here. For Blumhardt, kingdom work is always God’s free, redeeming work, a work that goes well beyond the walls and forms of the church. I think Blumhardt was even willing to contemplate that Jesus, the kingdom of God enfleshed, might emerge from within another religious tradition and thereby produce a different set of practices and perhaps even different confessions (within reason of course!), than those which have pertained within historic Christianity. Of course, there would be limits in this multiplicity, since the form of the life of Jesus is the form of the kingdom and is therefore the criteria for “discerning between the spirits.” But that form, the form of Jesus, according to Blumhardt was capable of producing all kinds of parabolic correspondences in all kinds of settings.

Wilhelm the new thing that God was doing among the Chinese. I think Blumhardt’s call to cease speaking in this way needs to be understood less as an absolute and once-for-all halt–such that one could now say a eulogy after the death of missionary and pastoral work–and needs to be understood more as a moratorium, a provisional measure which is meant ultimately to put the work of witness on a sounder footing, i.e., the footing of God’s own work. The appeal to the political here refers to Blumhardts conviction that the gospel of God’s reign is not about the soul’s “bye and bye” but about the real material conditions of humanity. God raised Jesus from the dead; God cares about the body; God cares about the body politic. The gospel proclaims the triumph of God over the ways of death, and therefore the gospel is invariably political. In Blumhardt’s context this was both a pedestrian and a revolutionary claim. It was pedestrian because the gospel had been appropriated by the state; and so of course mission work was political. It was revolutionary because what Blumhardt meant by “political” was counter to the status quo in Europe and the attempt to extend that status quo into the rest of the world. Put differently, the politics of God or God’s kingdom are always with and for the poor, the oppressed, and the dispossessed.

Wilhelm the new thing that God was doing among the Chinese. I think Blumhardt’s call to cease speaking in this way needs to be understood less as an absolute and once-for-all halt–such that one could now say a eulogy after the death of missionary and pastoral work–and needs to be understood more as a moratorium, a provisional measure which is meant ultimately to put the work of witness on a sounder footing, i.e., the footing of God’s own work. The appeal to the political here refers to Blumhardts conviction that the gospel of God’s reign is not about the soul’s “bye and bye” but about the real material conditions of humanity. God raised Jesus from the dead; God cares about the body; God cares about the body politic. The gospel proclaims the triumph of God over the ways of death, and therefore the gospel is invariably political. In Blumhardt’s context this was both a pedestrian and a revolutionary claim. It was pedestrian because the gospel had been appropriated by the state; and so of course mission work was political. It was revolutionary because what Blumhardt meant by “political” was counter to the status quo in Europe and the attempt to extend that status quo into the rest of the world. Put differently, the politics of God or God’s kingdom are always with and for the poor, the oppressed, and the dispossessed.4. What, in your view, is the current relevance of Blumhardt for our troubled times?

Christian’s Amazon Author Page:

http://www.amazon.com/

Christian’s Academia.edu Page:

https://bethel.academia.edu/