This is the sixth post of a series I will be writing over the next few months in which I reflect on my theological journey through Evangelicalism and “out the other side.”

Sir Tim Hunt, a Nobel prize winning scientist, got into a lot of trouble with his “the trouble with girls in the lab” gaffe. The science community reacted swiftly and voraciously–resulting in the resignation of Dr. Hunt from his university post and probably permanently scarring his legacy and his capacity for leadership in the scientific community. He meant it in jest, but since so many women in the scientific community have been working their tails off to achieve greater gender equanimity in a vocation that has been male-dominated inhospitable to women for so long, it was not received as humorous in the least. And for good reason.

But that got me thinking about women in the church. And it made me sad to realize that a similar “humorous” comment by a male pastor or leader in the Evangelical church–say at a denominational meeting or pastors conference–would not elicit anything near the protest that Tim Hunt’s comment drew. I bet many of the mostly-male audience would laugh right along.

I’m not shooting in the dark here. I’ve heard stories from female friends and former colleagues about the culture of Evangelical patriarchy. Whether experiencing explicit, outright gender bias through direct statements or oppressive policies, or encountering micro-aggressions in day-to-day interactions with male colleagues, pastors (or other supervisors), professors, members of a congregation, Christian friends, etc., it can be and often is a debilitating road. I’ve known not a few female seminary graduates who have left their Evangelical churches and ministries for more inclusive and respectful pastures of mainline, liberal/progressive settings. Some have left the ministry altogether, whether because there was no place for them (simply because of their gender) or because the burden simply became too much. It just wasn’t worth it.

For the remainder of this post, I thought I would reproduce an “Open Letter to Women in Ministry” that I published in 2011. The many responses that I received to that letter (both private and public responses) were surprising and very telling. I knew that women often experienced outright discrimination and I knew that conservative Evangelicalism was generally not a welcome, hospitable, affirming context for many women (my own seminary and denomination was a major piece of evidence in that regard). But I had no idea the extent of it–until I started receiving those responses.

I admit it feels rather strange to be writing on behalf of gender equality in Christianity, when the bigger and sexier debate now is over LGBTQ equality and acceptance in the church. But the two are connected.

Much of the conservative argument against affirmation of same-sex relationships is based on a theology of patriarchy and a gender essentialism that insists on differentiation and “complementarity” between men and women. In this argument, biological difference is divinely ordained, is equated with gender difference (male/female), and then forms the basis for the exclusion of same-sex, erotic/love relationships. And it perpetuates, because set in stone, the exclusion of women from certain positions of leadership–as well as countless other means of discrimination and oppression.

So, here’s the letter:

Dear Friends,

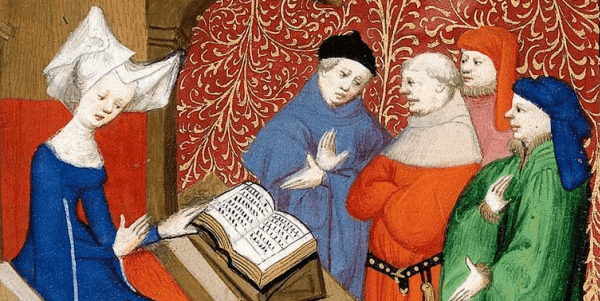

I know that seminary can be a mixed bag for women studying and training for vocational ministry. You likely encounter a confusing blend of support, apathy, and even downright hostility—perhaps all in a single day. I can’t imagine what it would be like to dedicate oneself to God and to devote oneself to the ministry, while sorting through such a mixed reception from fellow students, professors and church leaders.

I will never forget a female student who, after a class discussion on the theology of gender and ministry, shared—with tears in her eyes—her struggle with this confusing reception. She was about to complete her Masters of Divinity, with the goal of following her passion toward God’s leading in a church. But a troubling reality was settling in: the vast majority of the jobs posted by churches in her conservative denomination were explicitly designated “for men only.” No mixed message there.

Along with the bleak outlook in certain vocational areas of church ministry, women seminary students can regularly experience forms of oppression or derogation, whether striking or subtle, that can add up to a heavy burden. In many evangelical seminaries, this can be compounded by predominantly male faculties, predominantly male textbook authors, and even by male colleagues who question your right to be there. Of course, each experience is different and each seminary is different, but studies suggest that the increasing number of female students in seminary during the last 40 years has not always equated to a hospitable reception and nurturing environment. (For some reflection on these studies along with a recent study, see “Women’s Well Being in Seminary: A Qualitative Study, by Mary L. Jensen, Mary Sanders, and Steven J. Sandage, in Theological Education, Volume 45, Number 2 (2010): 99-116.)

If I may, I’d like to share a brief personal story. During my seminary days, I became theologically convinced of male headship in the church and home. I bought wholesale the argument that a “literal” reading of Scripture necessitates a patriarchal authority structure. We are fallen, sinful people, so we need well-defined, established and static authority structures. Male and female are equally worthy as human beings and both are created in the image of God. But men, not women, are designated the leaders. Perplexed? Don’t argue. It comes from the secret wisdom of God. And from the pen of Paul.

At that point, I hadn’t yet taken into account all of the theological complexities, hermeneutical and exegetical ambiguities and ethical implications that go with applying biblical texts to modern situations. For just one example of the exegetical ambiguities, I hadn’t realized that “head” (kephale), which most translations render “authority,” probably didn’t mean for Paul and his audience quite what we mean by it. Many Christians assume that the “head” language in 1 Corinthians 11 designates “authority over,” like a corporate CEO, rather than “source” or “origin” (see Phillip Payne’s Man and Woman: One in Christ). They sometimes miss other significant factors, such as Paul’s assumption that women “preached” regularly in public (1 Cor 11:5), that women and men are interdependent of each other and equally dependent on God (1 Cor 11:12) and that genuine Christian community depends on mutual submission (Eph 5:21).

While I wasn’t prepared to go all the way with my literal hermeneutic (I didn’t expect women to wear head-coverings in church or for men to keep their hair short), I was settled in my position; so much so that when the church where I served as youth pastor invited a woman to preach on a Sunday morning, I skipped the service. Thankfully, I didn’t make my stand known to anyone but the pastor (as far as I was aware). Had I broadcast my little protest, who knows what damage I could have done to the church—in particular to women who may have already struggled to embrace their status as glorious creatures, created in God’s image and equal to men in God’s economy (Gal 3:28)?

In the years since, I’ve changed my position on women in ministry and in the home. I don’t need to go into all the exegetical, hermeneutical, theological and ethical (not to mention practical) reasons for that. I’m sure you know them all anyway. But in sum, I came to realize that women and men are equal not just in “ontological worth” but in God’s salvation history and that God’s planned future for all people is an egalitarian community of mutually submissive, loving, and honoring relationships built on the Gospel of Christ, the Servant-Lord. Why should we structure our churches, families and relationships on the basis of past and present sins and failures rather than on the basis of God’s planned future for shalom?

Furthermore, I sense that Paul was concerned less with the details of gender relationships than he was with the advancement of the Gospel. His practical theology of church and family life was meant to serve the Gospel, much like the Sabbath was made for people, rather than people for the Sabbath. In our day, I believe that the Gospel is most powerful and effective when egalitarian relationships are the norm and when the equal worth of women and men is not just affirmed, but exemplified and practiced in the church and home. It’s one thing to proclaim an egalitarian theology, it’s another to support it and encourage it by practice.

I think back on my immature unwillingness to listen to a woman preach in church with embarrassment, shame and a sense of lost opportunity. But I use that now, I hope, to redouble my efforts to encourage you women who desire to follow Jesus into the often inglorious, sometimes thankless, and at times seemingly-homeless life of ministry.

I’m glad you are studying and preparing for ministry in whatever capacity and role God may call you toward. When you are discouraged with “opposition,” whether that opposition is explicit and brash or implicit and subtle, be assured that people do sometimes change their minds. More importantly, know that you are valued and loved and that the Church needs you.

In Christ,

Kyle Roberts

For more theology and society discussions and posts, like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook.