For awhile now, I’ve wondered why more hasn’t been written linking Kierkegaard’s thought with themes of liberation theology.

Christ as the “abased one,” rather than the already-resurrected Christ, the primacy of action over thought/doctrine/speculation, subjective appropriation of Christianity rather than objective understanding, the concrete/lived nature of faith over mental abstractions, Christ as a person rather than Christ as a doctrine, an incisive and extensive critique of Christendom and of “triumphal Christianity,” the duty to love one’s neighbor, and just generally the extent to which Kierkegaard faced into the dark side of the human condition: all these themes connect to aspects of liberation theology.

This is why I was glad but not surprised to see James Cone engage Kierkegaard in the first chapter of, The Cross and the Lynching Tree. Discussing the hopelessness that was felt by so many blacks in America amid slavery, segregation, and the horrifying but regular practice of lynching, Cone writes:

To sink down was to give up on life and embrace hopelessness, like the words of an old bluesman: “Been down so long, down don’t bother me.” It was to go way down into a pit of despair, of nothingness, what Søren Kierkegaard called “sickness unto death,” a “sickness of the self”–the loss of hope that life could have meaning in a world full of trouble. The story of Job is the classic expression of utter despair in the face of life’s great contradictions…

Unlike Kierkegaard and Job, however, blacks often refused to go down into that “loathsome void,” that “torment of despair,” where one “struggles with death but cannot die.” No matter what trouble they encountered, they kept on believing and hoping that a “change is gonna come.” They did not transcend “hard living” but faced it head-on, refusing to be silent in the midst of adversity…(19-20)

Cone goes on to say that,

African Americans did not doubt that their lives were filled with trouble: how could one be black in America during the lynching era and not know about the existential agony that trouble created for black people? Trouble followed them everywhere, like a shadow they could not shake. But the “Glory Hallelujah” in the last line speaks of hope that trouble would not sink them down into permanent despair–what Kierkegaard described as “not willing to be oneself”–or even “a self; or lowest of all in despair at willing to be another than himself.” When people do not want to be themselves, but somebody else, that is utter despair. (21)

[I would interject here that Kierkegaard also refused to “go down into that ‘torment of despair’ because he always had ready-at-hand what he believed to be the antidote to despair: faith in the suffering, abased Christ].

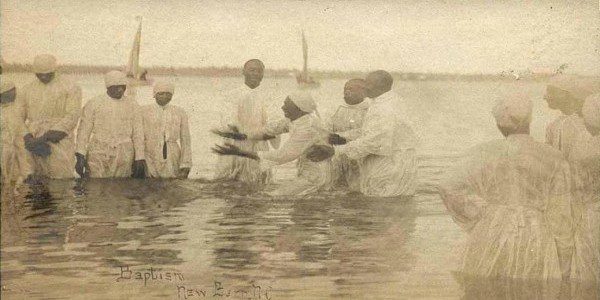

Image Source: Wiki Commons (Public Domain)

For more theology posts and discussions, like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook