I’m currently researching the virgin birth (more accurately: virginal conception) accounts in the gospels.

I came across quite the provocative paragraph in Gerd Lüdemann’s book, Virgin Birth? The Real Story of Mary and Her Son Jesus. Ludemann (a New Testament scholar) looks closely at the texts in question, both biblical sources and extra-biblical sources, and concludes from the evidence that the virgin birth story was an “apologetic” meant to counter criticism of Mary, the mother of Jesus, and thereby to rescue the reputation of both Mary and (derivatively) Jesus from those who wanted to discredit him. If Jesus had been the product of an “illegitimate” sexual relationship–or even of rape by someone other than Joseph (as Lüdemann suggests likely was the case)–then how could he be a legitimate Messiah? Also, the virgin birth story put Jesus on par with other divine figures, and solidifying the church’s claim to Jesus’ divine sonship and his lordship over the world.

Here’s the passage from the theological conclusions section of Virgin Birth?:

The statement that Jesus was engendered by the Spirit and born of a virgin is a falsification of the historical facts. At all events he had a human father. From that it follows, first, that any interpretation which fails to take a clear stand here is to be branded a lie. This includes all official Catholic dogma about Mary, and also the confessions of Jesus as the virgin’s son which are made every Sunday in Protestant worship. Secondly, comments by Protestant professors of theology who, together with their Catholic colleagues, fail to make any clear statement about the historicity of the virgin birth in any of their publications and prefer obscure formulations are also to be put under this heading. The fact that in the sphere of history all verdicts can only be probable is insufficient reason for being tolerant in questions of historical truth. (140).

He goes on to call out several biblical commentators by name, suggesting their inability or unwillingness to face the conclusion of the historical evidence for the falsity of the virgin birth accounts is either for reasons of cowardice or because they’ve become accustomed to the principle of “when in doubt” just side with the dogma of the church (141).

You don’t often see “fightin’ words” like this in academic writing. On the one hand, it’s a bit refreshing to encounter scholarship that’s so straightforward in its conclusions and even confrontational in the way it presents the implications. On the other hand, what should we make of the fact that numerous careful and reputable scholars come to a different conclusion than Lüdemann?

Are the reasons really cowardice or a conditioned deference to tradition (and, is that conditioned deference really so bad–assuming the historical or scientific evidence to the contrary isn’t a slam dunk?). For me, that historical judgments can only rise to the level of probability–not certainty–means our conclusions about past events should be shaped by humility. Especially when the character of the events in question (in this case, a virgin birth of the son of God) are, by definition, unrepeatable.

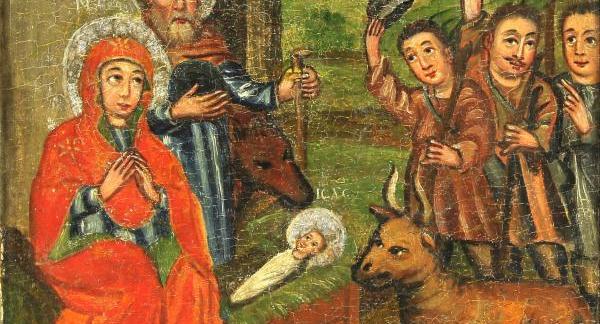

Image Source (slightly cropped)

For more posts and discussions on theology and society, like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook