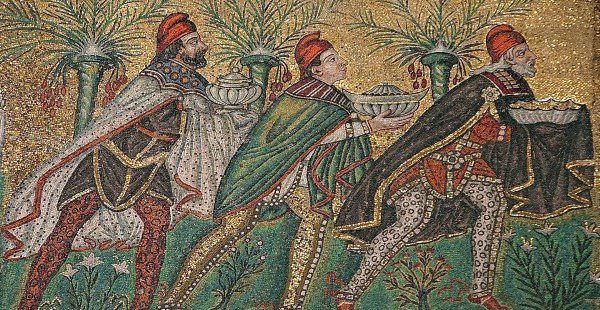

On Epiphany Sunday, Christians celebrate all sorts of events related to the stories surrounding the birth of Jesus.

But in the Christian (Latin) West, the celebration of Epiphany has primarily centered on the story in Matthew of the Magi, priests from the East who had heard news of Jesus’ birth and came to worship him and bring him gifts.

This story is celebrated as the very beginning of Jesus’ mission to the Gentiles, because the Magi, foreign Zorastrian priests, represented the non-Jewish world. From his birth, from his infancy, Jesus drew the Gentiles, those formerly considered unworthy and unclean, into the circle. From the very beginning of his life, Jesus intended his gospel, his salvation, to be all inclusive, universally expansive, non-territorial, not determined by ethnicity, skin color, nationality, or status. It was to be non-tribalist– radically open.

Acts 15 is also a great text for Epiphany Sunday, because it’s the story of the decision by the elders of the church in Jerusalem to include Gentiles into the Jewish Messianic fellowship (the church), without requiring they be circumcised (that is, become culturally Jewish in the strongest terms).

The elders sided with Peter, Paul and Barnabus over against the Pharisees, who had the “literal” reading of the Bible (see Genesis 17:9-14) on their side.

Luke Timothy Johnson, in Scripture and Discernment, suggests that Acts 15 provides the church (and theologians) with a picture of the “process by which the church reaches decision,” and a “paradigmatic story” by which churches even today can navigate difficult, complicated, and threatening events decisions.

I can’t recapitulate all his insights here, but the most important point Johnson makes is that the basis for the decision of the council of Jerusalem was not a literal reading of the authoritative text (i.e. the Bible), but rather a discerning attention to the ways and works of a redemptive God in the present of human experience.

This means that the church will often have to “catch up to God,” rather than to legitimate our present decisions by an ancient, textual authority.

As he puts it,

Will the church decide to recognize and acknowledge actions of God that go beyond its present understanding, or will it demand that God work within its categories” (91).

And again,

The only thing which could counter such a powerful precedent is the conviction that the God revealed in the past was active in these events now, and that God’s way of maintaining continuity in revelation may not be the same as ours. This, then, becomes the issue for the church’s discernment. Will it fall back on its deeply rooted (and revealed) perceptions of how God “ought” to act, or will it recognize that God moves ahead of its perceptions?

This is the challenge for the church in our day: how can we open ourselves up to the Spirit of God’s liberative action in the present, rather than remain captive to the categories our present — and past — understanding and expectations?