Martin Luther is often thought of as advocating a type of “forensic justification,” a kind of legal (and objective) declaration that a sinner is “just” or “righteous,” completely irrespective of that sinner’s “works” or contribution to salvation. did or didn’t do.

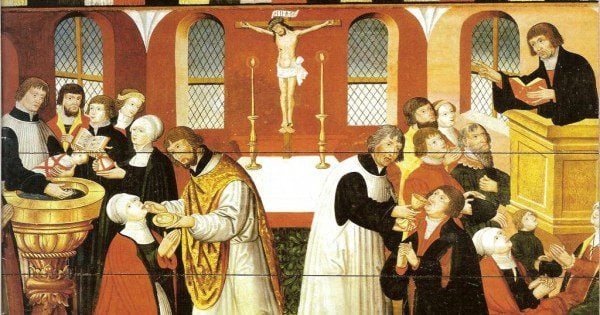

A forensic view of justification says that God “imputes” righteousness to sinners, declaring them to be perfect. What follows from justification is sanctification, which is the forgiven, redeemed person now working out their objective status subjectively. Justification and sanctification are then seen as distinct elements in salvation, even sharply distinguished from each other.

But Tuoma Mannermaa, in Christ Present in Faith: Luther’s View of Justification, has argued that this forensic view of justification, with its separation of justification from sanctification, is foreign to Martin Luther’s theology. It is far more consistent with the Lutheran scholastic theology that emerged in Luther’s wake, beginning with the Formula of Concord, a confessional document composed over 30 years after Luther’s death. This confession was responsible for disseminating much of Lutheran theology through the churches, but at least as Mannermaa argues, it ended up distorting what Luther actually taught about justification.

It overshadowed the “mystical Luther.”

In One With God: Salvation as Deification and Justification, Veli-Matti Karkkainen summarizes Mannermaa’s thesis (and the “school” which emerges from his influence on Luther interpretation):

The Mannermaa School rejects the distinction between justification and sanctification as foreign to Luther’s thought. They claim that for Luther the doctrine of justification is not a forensic term but rather a matter of Christ abiding in the heart of the believer in a “real-ontic” way…They also believe that theosis, rather than being a foreign Orthodox concept, is in fact one of the images Lutehr used to describe salvation (37-38).

Mannerma notes that Luther’s use of the phrase, “unio personaliis” (union of persons) is “perhaps the most intensive of the expressions Luther uses to describe the union between Christ and the believer. The image, which is close to mysticism, is an integral part of Luther’s doctrine of justification. (41).

For Luther, when faith is granted to a person by God’s grace (not through their own effort, works, or inherent virtue or love), that faith doesn’t just initiate God’s forgiveness and “imputation” of objective righteousness–it is a faith which transforms the person, from inside out.

Mannerman writes,

“Luther does not hesitate to conclude that in faith the human being becomes “God,” not in substance but through participation. This notion, which has been forgotten in Protestant theology, is an integral part of Luther’s theology of faith, if interpreted correctly (42).”

For Luther, then, the person for or to whom God grants faith, now really (ontically) “participates” in God. There’s a “union” of persons, the forgiven sinner and the Christ whom the sinner takes hold of by faith.

To really grasp the depth of the point Mannerma is making, it’s best to hear from Luther himself. In one of his published sermons (from the year 1525), Luther reflects on the Pauline phrase “all the fullness of God” (Eph. 3:19). (Note: this quote is from Mannerma’s text, which includes his emphases and translation preferences):

And so we are filled with “all the fullness of God.” This phrase, which follows the Hebrew manner of speaking means that we are filled in all the ways in which He fills a [person]. We are filled with God, and He pours into us all His gifts and grace and fills us with His Spirit, who makes us contagious. He enlightens us with His light, His life lives in us, His beatitude makes us blessed, and His love causes love to arise in us. Put briefly, He fills us in order that everything that He is and everything He can do might be in us in all its fullness, and work powerfully, so that we might be divinized throughout—not having only a small part of God, or merely some parts of Him, but having all His fullness. Much has been written on the divinization of man, and ladders have been constructed by means of which man is to ascend to heaven, and many other things of this kind have been done. However, all these are merely works of a beggar. What must be done instead is to show the right and straight way to your being filled with God, so that you do not lack any part but have it all gathered together, and so that all you can say, all you think and everywhere you go—in sum, all your life—is throughout divine.

Luther is perhaps more mystical than we assumed. And he’s also more medieval than we assumed, since many of us are used to thinking of Luther through the sharp dichotomy of justification and sanctification–and through the “objective” emphasis on imputed righteousness.