This is the fourth post of a series I will be writing over the next few months in which I reflect on my theological journey through Evangelicalism and “out the other side.”

A few years ago, it seems every evangelical blogger and theologian was writing about the “gospel.” They were proclaiming the “old, tried and true” gospel, recovering the gospel, renewing the gospel, restoring the gospel, or perhaps in some (fewer) cases reconfiguring the gospel. But in most of these cases, apart from notable exceptions, the intense energy went toward re-presenting a traditional Protestant, Evangelical (read: reductionist, individualist, escapist) understanding of the gospel.

I would venture a guess that most Evangelicals inherit or otherwise learn this very focused–which is to say narrow–definition of the gospel.

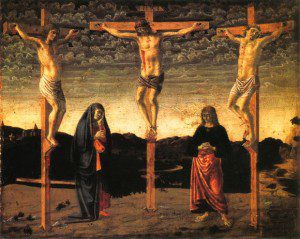

That narrow definition of the gospel is what happens when the gospel gets reduced to a single theory, or model, of the atonement called penal substitutionary atonement. A precursor to this model goes by the title, “satisfaction theory.” This is the idea that the death of Jesus on the cross procured the potential salvation for any sinners (and all people are sinners) who believe that message of salvation, trust in Christ for their salvation from their sin and from God’s wrath, and accept God’s forgiveness for their sin.  “Penal”=punishment. So, the punishment due sinners is taken on by Christ at the cross. Jesus becomes our “substitute,” who satisfies the justice/holiness of God and appeases God’s wrath.

“Penal”=punishment. So, the punishment due sinners is taken on by Christ at the cross. Jesus becomes our “substitute,” who satisfies the justice/holiness of God and appeases God’s wrath.

This “offer” of substitution is only made available through the mechanism of Christ’s atoning sacrifice. As the perfect, unblemished sacrifice for sin, Jesus was able to pay the penalty for all human sin–assuming people repent and accept the forgiveness offered by God through Jesus. This human act of reception (faith/repentance) opens up the “bank,” so to speak, to allow God to make the transaction: Christ’s perfect sacrifice and perfect righteousness for our sin. The “Great Exchange.” Typically, the offer is only valid for the duration of this life. Once you die, the offer is rescinded. (There are more roomy variations of penal substitution, which allow for exceptional cases: babies/toddlers who die before achieving sufficient understanding, “those who have never heard the gospel,” etc.).

Penal substitutionary atonement has pretty much dominated Evangelical understandings of the gospel since, well, the beginning of modern Evangelicalism.

And there’s a beauty to the logic. There are also strong indicators of its truth, or at the very least variations of this summary, in the Bible. It’s a liberating narrative, particularly for those of us whose greatest felt needs are internal (psychological, spiritual, emotional) and for those of us inclined to interpret reality through an individualist (selfish?) lens. To put it more strongly: the penal substitutionary model of the atonement seems an entirely adequate summary of the gospel for those of us who live our lives with relative privilege, economic stability, and physical comfort. The good news is that our sins are forgiven by God through Christ–forever and always. Oppressor, oppressed–doesn’t matter. Just confess, and all is washed away.

I’ve long found it–and still find it, actually–an emotionally powerful theology. It really does feel like “good news” to me. But look, I’m not wondering right now where my next meal is coming from.

What makes this (penal substitutionary atonement) understanding of the gospel “good news” for those on the underside of history? Those on the margins? The bullied, the abused, the brokenhearted, the hungry? When Jesus came preaching the “good news,” he declared that for them–for those occupying the underside–the good news is that they will inherit the kingdom! Just read the Beatitudes (Matt 5:1-11), if you don’t believe me. Read Luke 4:18-19, where Jesus announced his messianic mission to bind up the brokenhearted, give sight to the blind, and set the oppressed free.

The description of penal substitutionary atonement came easy for me, because–as an Evangelical for most of my life–that logic is inscribed deep into my bones. I don’t reject the core element that Christ’s death on the cross accomplishes something both objective (in God) and subjective (for us, for our benefit). In fact, the cross holds great emotional and spiritual power for me. It symbolizes the power of sacrifice, forgiveness, and reconciliation. But even more: it represents a real event of reconciliation that took place within history and within God. In the cross, God reconciled to the world. And in the reconciliation of God to the world, God made it possible for all people to reconcile with God. As I argued in my previous “Universalism” post, that reconciliation will eventually be accomplished in total, completely, absolutely, universally. Because the cross and resurrection of Christ changed history, God longs for and awaits our “acceptance of God’s acceptance of us.” That’s justification!

The problem is not that Evangelicals confess and proclaim a theology of substitutionary atonement: NT Wright warned that, while we ought not reduce the gospel to forgiveness of sins, there is an element of substitution that should be retained: “To throw away the reality because you don’t like the caricature is like cutting out the patient’s heart to stop a nosebleed.” I affirm the element of substitution, as an important–necessary, even–element of the gospel. But it’s one element, or one model, among many that should make up what we understand to be “the gospel of Jesus Christ.” And I think it’s a better reading of the gospels and of the entire NT, as well as a better theology, to affirm that God doesn’t need some mechanism to open his love and reconciliation to us. It’s one thing to say God uses Jesus and the cross, another to say God is bound to doing so, in some mechanical, deterministic, economic fashion, in order to forgive.

Regarding the Gospel, Scot McKnight rightly points out that the Gospel for too many evangelicals is solely a soteric gospel, a gospel reduced to the “benefits” of Christ’s death and resurrection for salvation from sin. McKnight calls it “a message of how to get saved from sins and how to be properly related to God.” He urges that we adopt an “apostolic gospel,” which puts the “Story of Israel and the Story of Jesus first, and not my personal salvation…” But the gospel of Christ is a message about what happened–and what continues to happen– within history through the incarnate Christ and the Spirit. It is the whole story of God reconciling Godself with the world, with creation, in and through Jesus and the Spirit. For Paul especially, I think, the gospel is the story of Jesus and of the cosmic reconciliation made possible by the cross. For Jesus, the gospel is the story of God’s kingdom arriving on earth, in time, in history–transforming and challenging the powers of the world and creating a new reality altogether.

The atonement and the gospel are intimately linked and related. But both have to do with more than “forgiveness of sin” and certainly with more than “appeasement of God’s wrath.” God’s wrath signifies, in my understanding, God’s deep concern that justice be done. And God wants us to participate in that justice, right here, right now; “on earth as it is in heaven.”

The atonement of Christ enables reconciliation with God, with each other, and with ourselves. The atonement enables a new way to be human, a new way to live in the world, a new and lasting hope. But it should also make us restless: restless for working toward a situation in which the full humanity of everyone is affirmed. This means what Evangelicals sometimes refer to derogatorily (though less probably than in the past) as “social justice” is as much a part of the gospel as “forgiveness of sins.”

NT theologian Richard Hayes sums it up better than I could, when he writes, in Proclaiming the Scandal of the Cross,

Paul almost never talks about “forgiveness of sins” because—-and here is the key point—he has a more radical diagnosis of the human predicament and a more radical vision of new creation. We need far more than forgiveness or judicial acquittal. We need to be changed. We need to be set free from our bondage to decay and liberated to participate in the life of the world to come, a life that has already invaded our broken world.