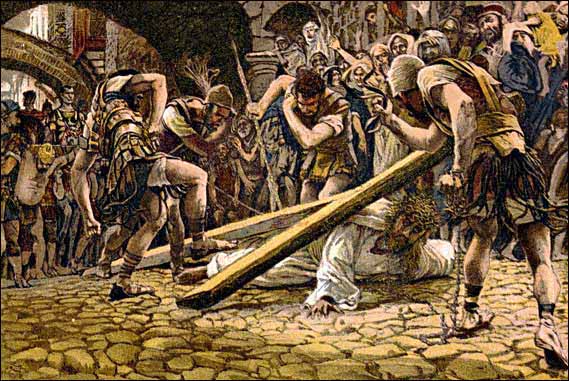

Today we celebrate the crucifixion of the Lord. Reread that sentence. We celebrate Jesus’ death. To Christians this is a great comfort. We know that Jesus died out of love for us in order that we might be saved. To many non-Christians this is an outrage.  Why should someone need to die in order that we might be saved? What does this say about the God Christians worship? Indeed, too often, Christians present the crucifixion in an unnuanced way so that it seems that God somehow needed a death – and not just any death, but the death of an innocent man – in order to be able to forgive sins.

Why should someone need to die in order that we might be saved? What does this say about the God Christians worship? Indeed, too often, Christians present the crucifixion in an unnuanced way so that it seems that God somehow needed a death – and not just any death, but the death of an innocent man – in order to be able to forgive sins.

That this is a distortion should be clear from the simple fact that Jesus forgave sins long before his death. I am not saying that Jesus’ death has nothing to do with forgiveness, but I am saying that it is not a matter of God’s anger being appeased by a human sacrifice before we can be reconciled. What I want to do in this piece is present a strand of the Christian tradition that is often overlooked when we think about Jesus’ crucifixion. It is my hope that, by integrating this strand into our thinking, we will see that the crucifixion has nothing to do with appeasing an angry God and that we will also see the essential character of the resurrection for our salvation, something that is lamentably ignored in many of the standard answers to the question, “Why did Jesus have to die?”

I want to start by looking at Chapter 2 of the Wisdom of Solomon. I will not reproduce the whole thing here, but it is worth your time to read it all, to get the fullest sense of the text.

1 For they [the ungodly] reasoned unsoundly, saying to themselves,

‘Short and sorrowful is our life,

and there is no remedy when a life comes to its end,

and no one has been known to return from Hades.

9 Let none of us fail to share in our revelry;

everywhere let us leave signs of enjoyment,

because this is our portion, and this our lot.

10 Let us oppress the righteous poor man;

let us not spare the widow

or regard the grey hairs of the aged.

11 But let our might be our law of right,

for what is weak proves itself to be useless.

12 ‘Let us lie in wait for the righteous man,

because he is inconvenient to us and opposes our actions;

he reproaches us for sins against the law,

and accuses us of sins against our training.

13 He professes to have knowledge of God,

and calls himself a child of the Lord.

14 He became to us a reproof of our thoughts;

15 the very sight of him is a burden to us,

because his manner of life is unlike that of others,

and his ways are strange.

16 We are considered by him as something base,

and he avoids our ways as unclean;

he calls the last end of the righteous happy,

and boasts that God is his father.

17 Let us see if his words are true,

and let us test what will happen at the end of his life;

18 for if the righteous man is God’s child, he will help him,

and will deliver him from the hand of his adversaries.

19 Let us test him with insult and torture,

so that we may find out how gentle he is,

and make trial of his forbearance.

20 Let us condemn him to a shameful death,

for, according to what he says, he will be protected.’

21 Thus they reasoned, but they were led astray,

for their wickedness blinded them.

Pope Benedict notes the extraordinary fact that Plato came to a very similar position:

In the Republic the great philosopher asks what is likely to be the position of a completely just man in this world. He comes to the conclusion that a man’s righteousness is only complete and guaranteed when he takes on the appearance of unrighteousness, for only then is it clear that he does not follow the opinion of men but pursues justice for its own sake. So according to Plato the truly just man must be misunderstood and persecuted in the world; indeed Plato goes so far as to write: “They will say that our just man will be scourged, racked, fettered, will have his eyes burned out, and at last, after all manner of suffering, will be crucified.” This passage, written four hundred years before Christ, is always bound to move a Christian deeply. (Introduction to Christianity, 292)

A little later Benedict continues:

The fact that when the perfectly just man appeared he was crucified, delivered up by justice to death, tells us pitilessly who man is: Thou art such, man, that thou canst not bear the just man – that he who simply loves becomes a fool, a scourged criminal, an outcast. Thou art such because, unjust thyself, thou dost always need the injustice of the next man in order to feel excused and thus canst not tolerate the just man who seems to rob thee of this excuse. Such art thou. St. John summarized all this in the Ecce homo (“Look, this is [the] man!”) of Pilate, which means quite fundamentally: This is how it is with man; this is man. The truth of man is his complete lack of truth. The saying in the Psalms that every man is a liar (Ps 116 [115]: 11 [DouayRheims]) and lives in some way or other against the truth already reveals how it really is with man. The truth about man is that he is continually assailing truth; the just man crucified is thus a mirror held up to man in which he sees himself unadorned. But the Cross does not reveal only man; it also reveals God. God is such that he identifies himself with man right down into this abyss and that he judges him by saving him. In the abyss of human failure is revealed the still more inexhaustible abyss of divine love. The Cross is thus truly the center of revelation, a revelation that does not reveal any previously unknown principles but reveals us to ourselves by revealing us before God and God in our midst. (Introduction to Christianity, 293)

According to these passages Jesus had to die because fallen man is a murderer. There is indeed a bloodthirsty deity. And our critics are right that such a deity is not worthy of worship, though that doesn’t stop them or us from paying him homage and sacrificing on his altar to this day. That deity is us.

The crucifixion of Jesus is the final condemnation of man. We who slaughter the innocent because they are “inconvenient” to us killed God’s own Son. Our sin was indeed condemned on the cross, not because God condemned Jesus, but because we did. In condemning Jesus, we condemn ourselves. That is why his death, as essential as it was in God’s plan of salvation, was not enough to save us. If Jesus had merely died on the Cross and not risen, Good Friday would be Black Friday. The gavel would have fallen once and for all, the verdict on humanity final.

Good Friday is only good because it is not the end of the story. Before we could be forgiven we needed to be exposed. Think of Jesus with the woman at the well. He read her like a book. Or the woman caught in adultery, brought out to be publicly shamed. Sin, before it can be forgiven, must be acknowledged; but because we run from the light, the light must search us out. Christ came to us to shine light on our most shameful practices so that we might be healed. Humanity has a history of scapegoating, of lynching the innocent. This running from responsibility, to the point where we would rather kill the innocent than own up to our mistakes (from Cain and Abel to the Holocaust to your friendly neighborhood Planned Parenthood), is what makes forgiveness impossible.

We find it very easy to justify ourselves. We must be shown that self-justification is impossible. The only justification of any avail is justification in Christ. The Cross prepares the ground for forgiveness by calling us out. When we behold the one we have pierced, the decision is before us in an ultimate way: will I or will I not admit my brokenness and my sin and seek forgiveness and a new way of life?

We know forgiveness is available if we have paid attention to Jesus’ public ministry. But forgiveness for this? For unjustified and selfish murder? For deicide?

If the disciples doubted for one minute that they could be forgiven for their complicity in the lynching of their Lord that doubt was answered in the resurrection. When Jesus came among those who had abandoned him and fled, he came again with words of forgiveness.

And so today, fellow sinners, we are exposed for who we really are so that on Sunday, when he says, “Peace be with you,” we will perhaps hear the true depth of those words.

Brett Salkeld is a doctoral student in theology at Regis College in Toronto. He is a father of two (so far) and husband of one.