It’s Labor Day, and I would welcome work.

At this time last year I was, by my own choice, in transition from a more conventional full-time job with a single employer to a more nebulous, semi-freelance one with multiple employers that define me variably as a casual employee, per diem employee, or contractor. It seems a strange choice to make for someone with a temperamental preference for structure and regularity, and I still wonder at that aspect of it. Truth be told, it was a trade-off in several ways. On the one hand, I gave up the guarantee of a regular work schedule and corresponding paycheck along with legally required benefits, in exchange for work that’s scheduled per assignment with the added responsibility of purchasing my own health insurance. On the other, I am more or less at liberty to determine my own availability without the risk of losing my job altogether, and doing the same kind of work in person rather than telephonically, and in a place I much prefer living in, is a lot less stressful. Even when my working days become full or hurried, I don’t begin the work week with any underlying dread or end it feeling drained.

It’s because of both the increased satisfaction and the lack of any guaranteed number of working hours that I would not begrudge having work this Labor Day. However, given the day’s significance in the history of labor justice (established contemporaneously with the promulgation of Rerum novarum, Pope Leo XIII’s groundbreaking encyclical on the condition of labor, it’s worth noting) and the fact that many people still lack the relative luxuries of job satisfaction or a negotiable schedule or both, it is important for meaningfully symbolic reasons (not to be confused with “merely symbolic”, thank you Karl Rahner) that it normally be reserved as a day off for non-emergent work. (The magnanimity of the fine folks at Maxwell House in giving a faithful employee one paid holiday in 53 years is not quite on the mark.)

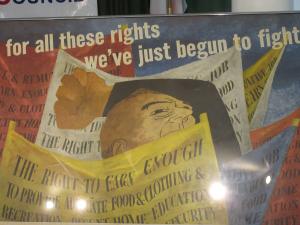

Keeping in mind both the conventionally employed who may lack leverage in the c onditions of their employment (generally more so the lower the wage) and the increasing number of people in situations like mine who may easily fall through the cracks in work regulations or even in the definition of workers, I spent this Labor Day morning rallying for a municipal ordinance currently under consideration that would require employers to provide up to six days per year of earned paid sick leave.

onditions of their employment (generally more so the lower the wage) and the increasing number of people in situations like mine who may easily fall through the cracks in work regulations or even in the definition of workers, I spent this Labor Day morning rallying for a municipal ordinance currently under consideration that would require employers to provide up to six days per year of earned paid sick leave.

Whether I and others with similar work situations would benefit under the proposed ordinance remains somewhat ambiguous. As it stands, the earned sick time would accrue gradually based on hours worked, so the available leave would not disproportionately affect the agencies I work for, nor would I want it to. But the city council is still considering certain possible exemptions, such as seasonal and per diem workers, and how to define them. Fortunately for me, my own job security does not hang on the question of whether or not I would be covered by the ordinance, but for certain others the stakes are clearer and higher. One home health nurse at the rally mentioned the importance of working parents being able to care for sick children, and representatives of parts of the immigrant community, which I serve in my own work, talked about the serious dilemma of risking their health or risking their jobs, and about a sense of being valued for their “input” rather than their humanity.

While the ambiguity of my own situation in relation to this particular local policy proposal is not an existential threat, it is illustrative of a broader trend away from what we now know as conventional models of employment, and from the security and protections that have come with it. Economic historian Louis Hyman recently summarized this trend and its accompanying trade-offs:

I am neither for nor against temping (or consulting, or freelancing). If this emergent flexible economy were all bad or all good, there would be no need to make a choice about it. For some, the rise of the gig economy represents liberation from the stifled world of corporate America.

But for the vast majority of workers, the “freedom” of the gig economy is just the freedom to be afraid. It is the severing of obligations between businesses and employees. It is the collapse of the protections that the people of the United States, in our laws and our customs, once fought hard to enshrine.

Hyman’s argument is that this loss of security is not simply an inevitable byproduct of an economic shift or of new technologies, but rather conditions of  labor, in every age, depend on a collection of social and moral choices. This is a point that resonates back to the origins of modern Catholic Social Teaching: whatever the conditions and nature of work, the dignity of work – and more fundamentally, of the human beings doing it – must be respected. Any changes to these conditions, whether positive, negative or profoundly mixed, require a moral response. The growing prevalence of a gig economy, with its flexibility and instability and everything else that comes with it, means that regulations and social mores must fill in its gaps, so that the work by which we earn the means to live be secure and dignified for all.

labor, in every age, depend on a collection of social and moral choices. This is a point that resonates back to the origins of modern Catholic Social Teaching: whatever the conditions and nature of work, the dignity of work – and more fundamentally, of the human beings doing it – must be respected. Any changes to these conditions, whether positive, negative or profoundly mixed, require a moral response. The growing prevalence of a gig economy, with its flexibility and instability and everything else that comes with it, means that regulations and social mores must fill in its gaps, so that the work by which we earn the means to live be secure and dignified for all.