I’ve already written some about Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings. My Plugged In review—the first installment, if you will—is here, and it concentrates more on the movie’s content stuff and negatives, including its 11-year-old boy/God. Then, over at FaithStreet.com, I dug a little deeper into Scott’s problematic deity … including what might be one of its biggest, most disturbing issues: The God we see on screen isn’t that much different from the God we read about in Exodus—one who feels so different from the kind and loving God that I most often picture.

But here, I wanted to dive into a third aspect of the story: How frustrating and ultimately rewarding our relationship with this multifaceted God can be. And Exodus does a pretty remarkable job in this area.

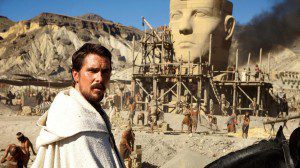

When we first meet Moses (Christian Bale), he’s pretty agnostic. He doesn’t have much faith in the Egyptian gods he’s been raised with. And even when he’s kicked out of Egypt and marries a God-fearing woman, he’s pretty skeptical of the whole concept.

“Is it bad growing up believing in yourself?” Moses tells his wife.

Now, this could be heard as just healthy self-confidence, but consider where he was raised—in the heart of an empire where kings were constantly building monuments to themselves. His half-brother, Ramses, had perhaps the biggest Ozymandias complex in history, but he wasn’t alone. Men—at least men of Moses’ stature—were gods. They believed in themselves. And that’s not altogether foreign to how we think of ourselves today. Even when we pay lip service to God, when it comes what we do every day, it sure looks more like we believe in ourselves.

Now, this could be heard as just healthy self-confidence, but consider where he was raised—in the heart of an empire where kings were constantly building monuments to themselves. His half-brother, Ramses, had perhaps the biggest Ozymandias complex in history, but he wasn’t alone. Men—at least men of Moses’ stature—were gods. They believed in themselves. And that’s not altogether foreign to how we think of ourselves today. Even when we pay lip service to God, when it comes what we do every day, it sure looks more like we believe in ourselves.

When Moses’ sheep scamper up the side of a sacred mountain and Moses goes to follow, he experiences something incredible. He gets smacked in the head with a rock and, when he comes to, floating in a bunch of mud, he sees a burning bush—and beside it a child-like “messenger,” who sounds a lot like God.

“I AM,” the boy says as Moses, and the soon-to-be prophet slowly sinks into the mud. When he truly comes to, he’s a new man—one who believes that God himself has given him a special task.

Now, catch the symbolism here: Moses is being baptized, in a sense. He is dying to his old spiritual self and becoming someone new, someone who God wants him to be. He is no longer the prince of Egypt—the vestiges of which he still clung to. He’s a Hebrew, one of the chosen people. When you see this scene through New Testament eyes, you can see it as a mirror image of what baptism is for us: A rejection of our old life and an embrace of the new, one in which is marked by God being at its center.

But here’s the thing I love about this: Even though Moses believes in God, he’s not all that different.

That’s very resonant for me. Perhaps for some people, baptism feels like marks the successful end of a long journey to God. But for me, baptism marked the beginning, one marked by seasons of doubt and anger. I’ve had a pretty messy walk with God. And Moses did, too.

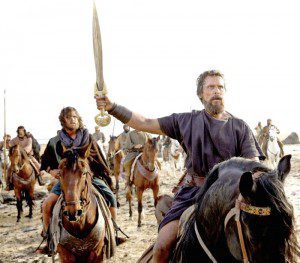

And so when God tells Moses that he’s looking for a general, Moses starts doing what generals do: He trains the Hebrews to fight back. He teaches them how to fight and begins launching guerilla attacks on his Egyptian adversaries. To trust, as it were, in themselves.

So God comes back to Moses and tells him to just … chill. “You want me to watch?” Moses says. “For now,” the Messenger tells him. And shortly thereafter, God launches his plagues.

Watching and waiting is hard for Moses to do—just as it is for us. “You don’t need me,” Moses says, sounding a little hurt. We’re people of action—people who like to feel needed. We want to pull our own weight. We like to see ourselves, I think, as the generals of our own lives. Sure, God might be our distant CEO, but we are our own bosses.

Watching and waiting is hard for Moses to do—just as it is for us. “You don’t need me,” Moses says, sounding a little hurt. We’re people of action—people who like to feel needed. We want to pull our own weight. We like to see ourselves, I think, as the generals of our own lives. Sure, God might be our distant CEO, but we are our own bosses.

But we’re not in a partnership with God: We’re His tools—a very, very different thing. He uses us for His purposes, and we have to sublimate ourselves to Him. And you know what? Sometimes that means just … watching. It means stepping back to marvel at the miracles God can perform.

God doesn’t need Moses. Not really. He doesn’t need any of us. But He loves us, and He wants us to be a part of His glorious plan—whatever that eventually looks like. And for us to be a part of that plan, we have to realize who’s in charge.

The rest of the movie is, as such, a pruning process. The plagues aren’t just about Pharaoh’s hard heart: It’s about Moses’ equally hard heart. At one point, Moses asks whether the plagues are meant to humble him, and then responds to the rhetorical question with a booming, “Never!” He’ll never bow. He’ll never lose himself to another.

But the Lord keeps working on him, just as He works on the Egyptians. Day by day, plague by plague, Moses’ faith is honed and refined and tempered. God was looking for complete capitulation. Not just, as it turns out, from Pharaoh. From Moses.

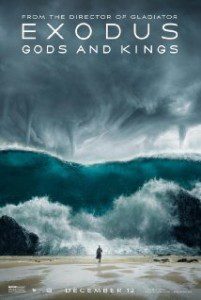

Finally, Moses leads his people out of Egypt and, apparently, to the edge of an impassible, impossible sea. God seems to leave Moses at a crucial juncture, as if inviting him to again trust in his own strength. But Moses has no more strength left. It’s up to God to save the people. There’s no other choice.

And then Moses does something interesting: He casts his sword—one given to him by Seti, the Egyptian Pharaoh—into the water. Frustration? Perhaps. But it seems to me this is also a symbol. He tosses away the final remnants of his previous life—the shreds he could never let go of. No longer was he Egyptian; he was Hebrew. No longer was he his own; he was God’s. He bows. He kneels. He becomes the tool that God needs him to be.

The next day, the waters have receded—and in the shallow, knee-high sea, Moses finds his sword. He takes it up, again a symbolic echoing (it seems to me) of a passage in Matthew: “Whoever finds their life will lose it, and whoever loses their life for my sake will find it.” Moses was willing to cast away everything—his wife, his son, his previous identity—for God. But God allows him to find it all again. He is a new man, yes, but a man whose old life was critical to who he became.

Y ou could read those shallow waters as yet another allusion to baptism. Before, Moses was almost forcibly baptized: He did not ask to see a burning bush or become God’s general. He was drafted. But there, at the edge of the Red Sea, Moses chooses to walk through the shallow waters, feeling for himself God’s miracle. And he leads a people with him.

ou could read those shallow waters as yet another allusion to baptism. Before, Moses was almost forcibly baptized: He did not ask to see a burning bush or become God’s general. He was drafted. But there, at the edge of the Red Sea, Moses chooses to walk through the shallow waters, feeling for himself God’s miracle. And he leads a people with him.

None of this negates some of Exodus: Gods and Kings negatives, of course. Lots of Christians still won’t be thrilled with what they see here. But for me, this one message found in the midst of this messy epic was really powerful and profound. I’m a lot like the Moses we see in this movie—oh-so proud, reluctant to bend my knee. But I’m on a journey, just like Moses is. God shows me new things about himself, and about me, every day. And hopefully one day, He’ll lead me to His promised land.