Disney has given us some pretty unlikely heroes: A wooden marionette; a flying elephant; a worry-prone fish. But maybe none has been quite as unlikely as Baymax, the inflatable robot from Big Hero 6.

The robot looks like a cross between John Candy and a ping-pong ball. He’s a robotic, vinyl healthcare provider—more a digital Mrs. Doubtfire than Dr. Manhattan. He’s about as intimidating as a fresh marshmallow.

Clearly, Baymax doesn’t look like a superhero. But in the end, that’s exactly what he becomes.

Hiro Hamada, a 14-year-old computer prodigy, may tell Baymax in the above clip that he’s not in pain. But he is. His older brother and mentor, Tadashi, died not too long ago in a horrible explosion. Without Tadashi’s guiding hand, Hiro has become reclusive, drifting back into aimless pastimes and allowing his formidable brain to be wasted in the not-so-healthy underworld of robot fighting.

Baymax—Tadashi’s own creation—doesn’t care a whit about bot fighting or why Hiro’s sulking in his room or any of that. He just wants to keep Hiro as healthy and as happy as possible. Baymax thinks of Hiro as his “patient,” and it doesn’t take a robot genius to figure out that what ails Hiro more than anything is grief.

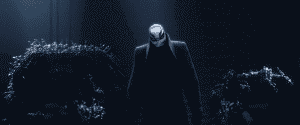

But when the two discover that Tadashi’s death might not have been an accident—that he was likely killed by someone who also took Hiro’s newly invented microbots (shown with the evildoer at right)—Hiro has an inkling of what might actually make him feel better: Catching the evildoer.

But when the two discover that Tadashi’s death might not have been an accident—that he was likely killed by someone who also took Hiro’s newly invented microbots (shown with the evildoer at right)—Hiro has an inkling of what might actually make him feel better: Catching the evildoer.

Baymax, as we know, is all about helping Hiro feel better. So he submits to the armor that Hiro puts on him. He allows Hiro to add to his programming—making him a ninja robot. He wants to help.

But when Baymax, Hiro and all of Hiro’s newly superheroed-up friends confront the villain, Baymax refuses to hurt the guy. Even though Baymax can ninja-chop wood with the best of ‘em, he can’t harm the villain. As a caregiver, it’s not in his programming. Hiro—desperate to see his brother’s murderer brought to terminal justice—ejects Baymax’ health-providing programming and turns him into a destroyer. A monster.

Big Hero 6, up for a Best Animated Feature Oscar Feb. 22, is really a story about grief—and how that grief and sadness can sometimes twist us into something we’re not. We’re horrified that Hiro temporarily turns Baymax into a digital angel of death … and yet at the same time, I wonder how many of us would be tempted to do the same thing. We feel for Hiro. We get it. Hurting someone is wrong … except.

We humans live in an ethical landscape painted in shades of gray. Oh, sure, it’s not like we’re completely relativist. We understand right and wrong. We understand good and evil. And yet, internally, we sometimes make exceptions for ourselves or others. We make excuses. We rationalize. Sure, we know the rules—and yet we tend to add amendments in the margins. Thou shalt not ignore stoplights … unless it’s 3 a.m. and we can’t see any cars and we’re really ready to get home. Thou shalt not cheat … unless we’re not cheating too badly and we have a really, really good reason. Thou shalt not kill … unless the killer deserves it. Unless we think his death might make us feel better.

But here’s the beauty of Baymax—the healthcare provider that Tadashi originally designed, not the revenge-machine that Hiro temporarily turns him into. He doesn’t get it. He can’t understand the very human instinct that, to feel better, we sometimes want to hurt someone else. It’s not in his programming.

Computers and robots aren’t inherently creatures of nuance. This is an oversimplification, I’m sure, but their very language—the binary system of ones and zeroes—is predicated on billions and trillions of “yes” and “no” answers. As much as they can “see” the world around them, they see it in black-and-white terms: To “understand” the exceptions and rationalizations that come naturally to us, they have to be painstakingly programmed into them.

I wonder if, in a way, that’s how God sees our sin. While He surely understands our all-too-human desire to rationalize and make exceptions—to give ourselves permission to do things we really know that we shouldn’t—to him, sin is sin. Bad is bad. There is no excuse, really. No adequate rationalization. To a perfect God, any blemish or imperfection looks pretty bad. We make our way in a fallen world filled with grays, but God is not a part of that gray world. He is bright and pure and good, and our instinct for sin is, in a sense, foreign to His being.

But by the same token, God’s love feels a little like that of Baymax, too. When God looks at us, He doesn’t see the sinner as much as He sees us—our hurting hearts. He knows our pain. He knows our anguish and anger. God, like Baymax, wants to heal us. He wants us whole again. And he has moved heaven and earth to bring us closer to Him.

At the end of Big Hero 6, Baymax sacrifices himself to save Hiro and someone else in dire need of saving. He does so willingly, even gladly. And in that moment, Baymax proves himself a hero—a marshmallow-shaped hero, yes, but a hero nevertheless. Perhaps Baymax, given his black-and-white binary world, would have a hard time defining the word “love.” And yet in a way, he showed Hiro what it means.

At the end of Big Hero 6, Baymax sacrifices himself to save Hiro and someone else in dire need of saving. He does so willingly, even gladly. And in that moment, Baymax proves himself a hero—a marshmallow-shaped hero, yes, but a hero nevertheless. Perhaps Baymax, given his black-and-white binary world, would have a hard time defining the word “love.” And yet in a way, he showed Hiro what it means.

Love, at its purest, is binary. It, as Paul says, “bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends.” No exceptions. No amendments. And as such, a robot like Baymax understood it well.