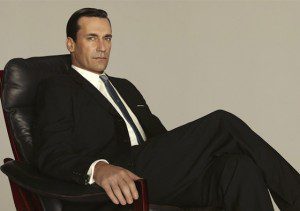

Don Draper doesn’t just do advertising. He is advertising.

Look at him. Just look.

Cool. Crisp. Nattily dressed. Meticulously combed. It’s as if he stepped off the back cover of one of his own print ads. Mad Men’s prime protagonist (played ever-so-smooth by Jon Hamm) is a picture of vigorous, middle-age success. This, the picture tells us, is a man who knows the proper wine to pair with ham, who can fix a busted faucet and who will always make more money than you.

He’s also, as Mad Men viewers know, an utter fraud—a nowhere man named Dick Whitman who remade himself following the Korean War. He built a new persona for himself, a new life and career built on nothing but ambition and ethereal daydream. Andre Agassi once told us that “image is everything,” but it was Don Draper who lives it. He’s the picture of a TV dinner that hides what’s inside the box, a travel brochure to Palm Springs that forget to mention the heat.

And as viewers, we react to him much as we would a well-crafted ad. We’re not blind: We know he’s a cad, just as we know that drinking the right soda or beer won’t make us prettier or smarter or more desirable. We know that driving the car with the leather seats and luxury insignia won’t actually make us faster or more successful or better. And yet we still feel the tug.

I don’t need a Mercedes AMG GT. Owning one would add several layers of worry and complication to my life. Where should I park? What if someone scratched it? It costs how much to run the thing?

But do I want one? Yes. Yes I do. Such is the power of beauty, of suggestion, of temptation. Those things made Don Draper who he is. And, as we’ve seen for seven seasons, they hold the root of his very destruction.

AMC’s Mad Men has lots of problems. But dig underneath it all, and you unearth an intensely moral  core. Mad Men lets us see the dream Don Draper offers, the dream he lives. It offers the promise. It is, in essence, an incredibly attractive advertisement of one man’s life. And then it strips it down, piece by piece, layer by layer, until we realize what we always knew: That dream was nothing more than a dream, the promise no more than a promise. It was empty. Don is empty. And he turned his back on what might fill him.

core. Mad Men lets us see the dream Don Draper offers, the dream he lives. It offers the promise. It is, in essence, an incredibly attractive advertisement of one man’s life. And then it strips it down, piece by piece, layer by layer, until we realize what we always knew: That dream was nothing more than a dream, the promise no more than a promise. It was empty. Don is empty. And he turned his back on what might fill him.

I’ve already mentioned “Severance,” Mad Men’s spring premiere for its final season (it aired April 5). The episode is bracketed by Peggy Lee’s breezy, weary “Is That All There Is?” a beautifully bitter ballad that Don could’ve written himself. One of the verses reads:

And when I was 12 years old, my daddy took me to a circus.

“The Greatest Show On Earth.”

There were clowns and elephants and dancing bears.

And a beautiful lady in pink tights flew high above our heads.

And as I sat there watching, I had the feeling that something was missing.

I don’t know what, but when it was over,

I said to myself,

“Is that all there is to a circus?”

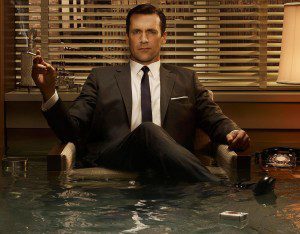

Don Draper has been living the circus for seven seasons. He’s had two picture-perfect wives, fathered lovely children, bedded countless beauties and swilled a staggering number of cocktails. Occasionally, intimacy—real intimacy, the tough, tricky, eternal kind—reached out to him. Part of him longed to follow. But he never left the circus, with its elephants and dancing bears and ladies in tights. He could never leave the show—the vacuous show that with his work he propagates, with his fictitious life he endorses, with his habits and predilections he cements. Admittedly, I haven’t watched every episode of Mad Men. But in every episode I’ve seen, Don Draper seems pulled by two forces: The transient, superficial pleasures with which he’s grown so acquainted—the booze, the women, the lifestyle—and a longing for something more. Something permanent. Love. Family. Friendship. Belonging.

“Severance” is just the most recent example. When Rachel, an old flame of his (and one of the few people who saw through his self-made sheen), dies unexpectedly, Don visits her New York apartment where her friends and family are sitting shiva (a Jewish mourning ceremony). He sees the dead woman’s children on the couch, talks with her frosty sister who knows exactly who he is. “How’s your family?” she asks. And when Don asks the sister, a bit sheepishly, how Rachel lived, Barbara offers this broadside:

“She lived the life she wanted to live,” she says. “She had everything.”

If Don Draper dies, will someone say the same of him? You could say he lived the life he wanted to live. You could say he had everything.

But when Don looks on at the quiet shiva—a memorial to a woman much beloved—both he and we know that his everything is an empty thing, a superficial jar of clay with nothing inside.

But when Don looks on at the quiet shiva—a memorial to a woman much beloved—both he and we know that his everything is an empty thing, a superficial jar of clay with nothing inside.

“One’s life does not consist in the abundance of his possessions,” Jesus says in Luke 12:15. And here’s the central tragedy of Mad Men: On some level, Don Draper knows it. When he and Peggy Lee ask, is that all there is, he can hear the whisper of a “no” somewhere. The secret to life isn’t in what we collect, but what we do. It’s not what we buy, but what we give. It’s so cliché. It’d never work as a bit of advertising copy. And yet it’s true.

There’s a lot of speculation that Don Draper will die before the last episode ends, and in “Severance” his story is surrounded by death: When he takes a tumble with a one-night fling, red wine splatters the carpet like blood. When he meets a waitress who feels creepily familiar to him, a co-worker calls her “Di,” the name slicing through the air like an order. There’s a sense of doom in every encounter now, and I half-wonder whether show-runner Matthew Weiner had in mind the familiar verse “The wages of sin is death” when he titled the show “Severance.” Don has always been in the business of sin—be it his own or his ability to peddle low-grade temptation to the masses. Now, perhaps, his final check is about to be cut.