If he was alive, Orson Welles would’ve celebrated his 100th birthday today. Perhaps he’d celebrate it by watching his cameo in The Muppet Movie (where I first saw him) and sipping a glass of inexpensive wine.

If he was alive, Orson Welles would’ve celebrated his 100th birthday today. Perhaps he’d celebrate it by watching his cameo in The Muppet Movie (where I first saw him) and sipping a glass of inexpensive wine.

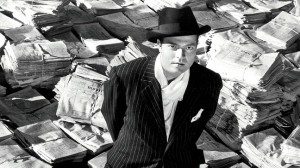

Welles might be one of the most influential entertainers ever. The guy did a little bit of everything, from avant-garde Shakespearian stage productions to headline-grabbing radio theater (his 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast triggered nationwide panic) to, of course, movies. Citizen Kane, his very first film, released in 1941, was a masterpiece—one that almost didn’t see the light of day, thanks to William Randolph Hearst (who believed, with good reason, that the film was about him). It’s still considered to be the best American film in history.

It’s not an overtly religious pic. But its main theme is as old and as true as the Bible itself: You can’t fill your soul with stuff. No matter how big you build your house, it won’t necessarily be home.

We first see Charles Foster Kane, the movie’s flawed protagonist, as an old man about to die, muttering the enigmatic word “Rosebud” as a snowglobe tumbles from his hand. From thereon, his character is peeled like an onion, layer by layer. We learn about his life through a series of interviews—his days as a hungry newspaper publisher, his failed run at politics, his fractured and troublesome love life. We learn that, as a child, he was taken from his parents to go live with a wealthy banker in order to be given all the advantages wealth can bring. Through this winding, tumbling story, we meet a man whose talent and ambition drove him to unimagined heights, and yet his life seems curiously empty. His massive castle Xanadu is stuffed with treasures he’s never bothered to unpack. His wealth is squandered on gold plating and zoo animals. When he dies, he dies practically alone.

Rosebud (seven-decade-old spoiler alert) was the name of his childhood sleigh. When Kane died, his last thoughts turned to a youth he never had, to a life he could never find. Kane had it all. But what he wanted was something else entirely: He wanted Home.

Those sorts of themes are pretty common in movies, I suppose. Ever since Macbeth—heck, maybe ever since King Saul—we’ve seen that wealth and power and unimaginable advantages don’t equal happiness. And, in a strange way, you can even see a twist on that theme in Avengers: Age of Ultron.

There’s a little bit of Charles Foster Kane in our superheroes. Combined, they’ve got loads of super strength and super agility and super-full bank accounts and super charisma. They lack for nothing, it would seem.

And yet when Wanda Maximoff starts playing with their psyches—when they’re touched by fear and doubt and guilt—how does she twist their thoughts? Toward what they can’t have. Steve Rogers/Captain America imagines his one true love, Peggy, young and vibrant. Natasha/Black Widow recalls her horrific youth, maybe after she was yanked away, Citizen Kane-style, from her own family. Bruce Banner longs to be normal, to have a regular life complete with wife and kids. Tony Stark is

And yet when Wanda Maximoff starts playing with their psyches—when they’re touched by fear and doubt and guilt—how does she twist their thoughts? Toward what they can’t have. Steve Rogers/Captain America imagines his one true love, Peggy, young and vibrant. Natasha/Black Widow recalls her horrific youth, maybe after she was yanked away, Citizen Kane-style, from her own family. Bruce Banner longs to be normal, to have a regular life complete with wife and kids. Tony Stark is

practically the superhero embodiment of Kane, what with his smarts and ambition and unimaginable wealth. But when Wanda touches his mind, he imagines losing what, perhaps, he values almost above it all—this makeshift family of Avengers.

Each, in their own way, has their thoughts turn home—not a house, but a sense of belonging and community and love that lies at our understanding of home. For them, home is a fragile thing. It’s often been lost—lost in becoming who they are.

I love the fact that, when they go to regroup after Wanda’s interference, they go “home”—not to Avengers’ headquarters, but to a picture-perfect farmhouse. Turns out that Clint Barton (Hawkeye), when he’s not saving the world, is a family man with a great wife and cute kids and a list of home-improvement projects. ‘Cause that’s the thing about home, isn’t it? It may be great, but if you love the place, you always think it can be better.

And when we see Clint’s family and farmhouse, we understand him so much better—and the real risks he takes when he’s off fighting aliens and robots. He’s risking an empty spot at the dinner table or a Sunday afternoon tea party with his daughter. He’s risking not just his life, but his role as a husband and father. He’s risking it all. And in a way, his family is risking it with him.

Superheroes often reject a real home life to do their work. But because Clint has a home life, I think we understand the sacrifice a little better. They’re heroes, sure. But they don’t have a home. Not really.

Now, obviously, the concept of home—of hearth and family, homecooked meals and LEGOs and all the feelings of love and comfort that those things just ooze—isn’t a uniquely Christian concept. But it is, I think, a spiritual one. Our longing for home is one of the soul. Physically, we need shelter. Intellectually, we need a place where we can run our lives as efficiently and as comfortably as possible. Emotionally, we may crave granite countertops in our kitchen or a sunny master bedroom. But when we think of home, it’s about more than running water or a living room with a wall for your big-screen TV. something that can’t be empirically measured. There’s a little bit of mystery to home—something maybe even a little transcendent.

Now, obviously, the concept of home—of hearth and family, homecooked meals and LEGOs and all the feelings of love and comfort that those things just ooze—isn’t a uniquely Christian concept. But it is, I think, a spiritual one. Our longing for home is one of the soul. Physically, we need shelter. Intellectually, we need a place where we can run our lives as efficiently and as comfortably as possible. Emotionally, we may crave granite countertops in our kitchen or a sunny master bedroom. But when we think of home, it’s about more than running water or a living room with a wall for your big-screen TV. something that can’t be empirically measured. There’s a little bit of mystery to home—something maybe even a little transcendent.

There’s a reason why when we think of heaven, we think of it as our ultimate home. We don’t know what it’ll look like, exactly. But we know how it should feel. Because all of us know the feeling—and when it’s missing, we feel its absence.

Rosebud, Kane said. It’s just the name of a silly sled. Part of the genius of Orson Welles is that he made it stand for so much more.