Most folks would call The Post a straightforward docudrama. Maybe if you squinted really, really hard, you might find a hint of a low-key thriller in there, despite the lack of shootouts and car chases.

But a horror movie? Puleeeze.

Then again, most of us aren’t The Post’s Kay Graham.

Graham, played by Meryl Streep, is the publisher of the titular Washington Post—a pretty frightening position itself, and one she never expected to hold. Her father bought the paper. Her husband ran it until he committed suicide. She never aspired to be publisher: She was best known as one of Washington D.C.’s most prominent socialites—dining with the powerful of both political parties.

Even though newsprint ran in her family’s blood, Graham became publisher by default. And as the first female publisher of a major national daily in 1971, when the term “housewife” was still a thing and jokes about “crazy women drivers” were common, her doubters are legion, even inside her own circle.

The Post wasn’t quite the journalistic force it’d later become during Watergate. The New York Times was the newspaper industry’s undisputed leader: In The Post, the Times building looks and feels just a bit like a church, right down to stained glass accents and a sanctuary-like lobby. And as always, the Times has uncovered a big story: Neil Sheehan, one of the paper’s top reporters, has access to what would become known as The Pentagon Papers, a massive and classified study on U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Those papers contain scads of explosive revelations about four U.S. administrations—including the fact that American presidents knew long ago that Vietnam was unwinnable, but kept sending soldiers to die in the conflict anyway.

President Richard Nixon was in power at the time. His administration wasn’t implicated in the Papers, but it felt like their publication posed a threat to the office itself. Two days after the first story was published, it took the paper to court. The Times had little choice to stop publication.

Scary? For folks in the media, you bet that’s scary. Reporters see themselves as explorers of sorts, peering into dark corners and prying into basements, looking for monsters. Now, Sheehan found a big one, but he’s told not to talk about it. For some, that’s pretty horrifying.

These developments must’ve struck Graham as frightening, too, but in a distant sort of way—strange lights and sounds coming from a house in the neighborhood. Sure, she thought about the implications, but her paper at least was free to operate as she and her staff saw fit. After all, the Post didn’t have The Pentagon Papers. She may have wondered, she may have worried. But the truly terrifying Nixon administration was haunting someone else’s house. It had nothing to do with her.

Until she learns that her paper, too, has access to the Pentagon study. The horror is at her door.

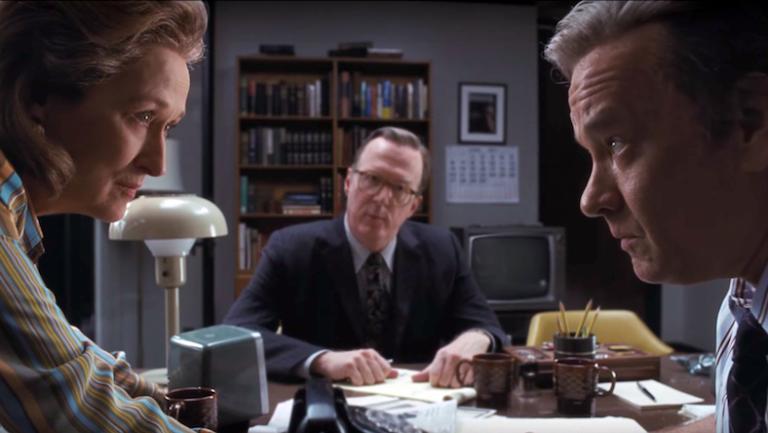

For most of the characters in The Post, there’s only one way to deal with the Pentagon Papers: You publish. “What will happen if we don’t publish?” Ben Bradlee, the Post’s new, brash editor (played by Tom Hanks), asks. “We will lose! The country will lose!”

Easy for him to say. In a way, he and his staff have nothing to lose. Sure, they could all go to prison. But as Ben’s wife, Tony, points out, his reputation will only be burnished by the controversy. His standing as a journalist will only grow.

But Graham’s not a journalist—not really, not then. She’s a socialite who might lose most of her dearest friends. She’s a mother who’d like nothing more than for her own children to grow up in the newspaper business, just as she did. She’s a businesswoman who just took the Post public. If the Post publishes the papers and the courts side with the Nixon administration, that business—her family’s legacy—could go under.

“If we don’t hold them accountable, who will?” Ben blusters.

“We can’t hold them accountable if we don’t have a newspaper,” Graham says, and you know what? It’s a valid fear.

Tony reminds Ben—and us—that while Ben has nothing to lose, Graham could lose almost everything.

Terrifying. And to Streep’s and the film’s credit, we feel Graham’s fear, more even than the Constitutional crisis brewing. The Post doesn’t feel as much like a saga over the fate of a free press as the battle in the soul of one women, faced with a fearsome decision that she’d never thought she’d have to make.

Spoiler warning, I suppose, though history spoiled the real Pentagon Papers saga decades ago: Graham elects to publish. She does so against the advice of her closest confidants. She does so even though she knows full well that she could go to prison. She does so even at the risk of her beloved paper.

“Let’s do it,” she says. And so they do.

Lots of folks suggest that The Post is a fable of sorts—a reflection meant to draw attention to our modern political troubles and fears. As those in power point to mainstream media and scream “fake news,” the movie suggests that a free and aggressive press is more necessary than ever.

But I find the themes in The Post more universal than that.

Look at the sexual harassment scandals rocking the entertainment and political worlds—how men in power were allowed to engage in acts for years and decades without fetter. Why? Fear. People feared for their jobs, feared alienating those same powerful people. North Korea continues to boast about its growing nuclear program to make the world fearful of its power. The year 2017 saw several mass shootings tailored to sow fear.

And we look in our own lives, too. Fear surrounds us. Infects us. Fear for our jobs and children. Fear of a loss of power or prestige. Fear of disaster. Fear of the future. We are hemmed in by bogeymen on all sides, and it can paralyze us.

We see the paralytic power of fear so often in horror movies, Dracula staring down his victims, too frightened to move. It can happen to us, too.

Graham could’ve been paralyzed by fear. I might’ve been too, had I been in her shoes. She might’ve folded under that fear. Looking at what she had to lose, it’d be hard for me to blame her much.

But she didn’t. Like any good horror movie protagonist, she stared right back into that fear like Van Helsing, armed with just a cross and holy water. She faced her fear and thus vanquished it, and so she won the day.

Do not be afraid, the Bible exhorts again and again. “Fear not, for I am with you,” Isaiah 41:10 says. “Be not dismayed, for I am your God.” 2 Timothy 1:7 tells us that “God gave us a spirit not of ear but of power and love and self-control.”

Listen, those words in the Bible are sometimes hard to hear. I get scared about the present and future, too. I can be frightened rather easily. Just ask my parents how many times I leaped in bed with them when I was sure something was crawling around my room.

But as an adult, I’ve learned that making decisions based in fear will almost guarantee a bad decision. When we’re scared, we can’t cave into that fear. When we’re scared we have to face that fear and, more importantly, look past it—look to what is actually the right thing to do.

Most every one of us will have something to fear in the coming year. That’s almost a guarantee. And in the midst of that fear, we’ll be asked to make a decision. What decision we make in that moment will say a lot about us. Our decision might impact a very small circle of influence or be heard around the world.

If and when that moment comes for me, I hope I remember the example of Kay Graham in The Post. The example that others have set, beginning with Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Fear is real. It is inescapable. And it is, indeed, terrifying. But the best way to deal with fear is to plow right through it, to the righteousness that lies on the other side.