In a quiet week at the box office, an unassuming film called Freud’s Last Session might’ve made its way to a theater near you. It’s likely not going to be a blockbuster.

But just because people haven’t seen it doesn’t mean they shouldn’t. For anyone interested in faith, Freud’s Last Session might be a must-see.

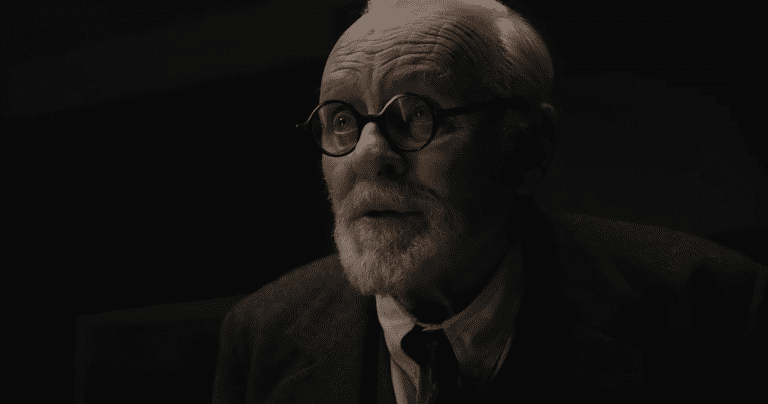

Freud’s Last Session, based on a play that was, in turn, based on Armand Nicholi’s book The Question of God, takes us into Sigmund Freud’s London flat in 1939. Europe stands at the brink of another cataclysmic world war. But here, another battle forms—one between Freud, the eminent psychoanalyst (played by two-time Oscar winner Anthony Hopkins), and a young Oxford don named C.S. Lewis (Matthew Goode).

The question at hand? The biggest I can think of: The existence of God.

Lewis had yet to publish his most famous Christian works. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe would be published in 1950. Mere Christianity (based on his wartime radio talks) was still 13 years from print. But his 1933 book The Pilgrim’s Regress had marked Lewis as both a scholar and a Christian, and Freud wanted to talk with the scholar and former atheist. He was curious. About what?

“Why someone of your supreme intellect would suddenly abandon the truth and then embrace a ludicrous dream,” Freud says. “An insidious lie.”

“And what if it isn’t a lie?” Lewis asks Freud. “Have you ever considered how terrifying that would be?”

As the world teeters on the precipice of war, Freud and Lewis discuss meaning, sex, death and, most especially, God. And while the movie may be fiction, creator Mark St. Germain clearly did his homework: Much of the dialogue seems almost directly pulled from the characters’ own real-world writings.

“What if God wants to perfect us through suffering?” Lewis tells Freud when the psychoanalyst challenges him on the problem of pain. “Make us realize that happiness, real happiness, eternal happiness can only come through Him. If pleasure is His whisper, pain is His megaphone.” For any avid reader of Lewis, they’ll recognize the echo from The Problem of Pain, right down to the word megaphone.

But perhaps the most compelling moments in the movie are the characters’ most unguarded.

The real Lewis served in World War I, and he once wrote a friend that the memories of it “haunted my dreams for years.” When London sounds an air raid alarm, sending Freud and Lewis scurrying to a church-based bomb shelter, Lewis seems absolutely terrified. Freud comforts him then. But when they return back to Freud’s flat, Freud uses that fear as a weapon.

“You most certainly did not behave like a man who took great comfort in his last days in this terrible, terrible world, did you?” Freud accuses. “Where was your great faith? Where was your precious joy meeting your beloved Creator? Disappeared. Why? Because you know … that He does not exist!”

But Freud himself seems to unintentionally echo Christian thought and theology at times. When Lewis accuses Freud of being a “walking contradiction,” Freud easily admits as much.

“Ah, well, I’m human,” he says. “I’m inherently flawed and I’m deeply damaged. And no doubt I am damaging to others.”

And that, Lewis could’ve responded, is why we’re all so desperately in need of a Savior. We’re damaged goods, all of us. And in the shards of our own brokenness, we cut those closest to us. We hurt. We fear. We rage. And ultimately, no amount of psychoanalysis can truly, completely fix us. We need grace and love and God.

Freud’s Last Session is not about one man or the other “winning” the argument. Freud, dying of cancer, did not say the Sinner’s Prayer. Lewis would go on to write his most beloved Christian books. And at parting, Freud quips, “If you’re right, you’ll be able to tell me so. If I’m right, no one will ever know.”

And then Freud does an odd thing: He leans his head against Lewis’ chest.

“We will meet again, perhaps,” he says.

It’s not an admission. But it is a softening.

Throughout Freud’s Last Session, the atheist psychoanalyst and the Christian professor go at each other with rhetorical sword and shield. They argue. They sometimes shout. But they also get to know each other. And perhaps it’s that knowing—to see the vulnerability of the man as much as hear the strength of their arguments—that our defenses drop just enough to listen.

Freud doesn’t believe in God when Lewis leaves his presence. But he doesn’t seem to believe that religion is clinical insanity, either. Perhaps there is something more.

Perhaps.