Salon’s Edwin Lyngar thinks that Christian films are awful.

Salon’s Edwin Lyngar thinks that Christian films are awful.

He’s not alone in that. I have seen my share of awful Christian films myself. But Lyngar believes all Christian films are downright horrid—and they’re all horrid in much the same way. He writes:

You can’t judge Christian films like other movies, Any casual examination shows them to be conventionally terrible without exception. But they are not meant to be good, but rather they are designed to deliver pointed messages, spurring audiences to promote and support established political and religious powers.

He writes that “many” of the films he watched (for this story, presumably) were critical of secular reporters and reviled anyone who espoused a secular worldview. “Every single film I reviewed features some variation of the Christian persecution complex,” he writes. And then he adds that, “The people who create and consume Christian film are neither mature nor reflective,” but rather are “superstitious, afraid and tribal,” while their stories are “borderline psychotic.”

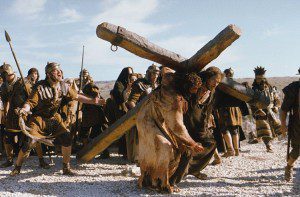

From what I gather, Lyngar watched three Christian films for his story: The Passion of the Christ, God’s Not Dead and Left Behind (the 2014 version). It’s possible that Lyngar watched more but were edited out by Salon’s crack team of editors. But as it stands, three films seem like an awfully small sample size to make some awfully sweeping statements.

Naturally, I’d disagree with many of Lyngar’s characterizations even with the three movies he saw. It seems rather unfair, for instance, to cast Jesus’ crucifixion in The Passion of the Christ as a “variation of the Christian persecution complex.”

But three movies? Reaching back a decade for one of them in a year when the diversity of Christian moviemaking hit, arguably, its peak?

There was no Heaven is for Real here (a quiet story about a four-year-old who believes he went to heaven) or Son of God (a retelling of what Jesus did here on earth). He did not cast eyes on the comedy Mom’s Night Out (pictured at right) or the romance The Song—a re-imagining of the Song of Solomon. He skipped sports movies like When the Game Stands Tall, or the critically acclaimed drama The Good Lie (85 percent “fresh” on rottentomatoes.com). And that’s, what, about a third of the Christian movies that have been released nationally just this year?

There was no Heaven is for Real here (a quiet story about a four-year-old who believes he went to heaven) or Son of God (a retelling of what Jesus did here on earth). He did not cast eyes on the comedy Mom’s Night Out (pictured at right) or the romance The Song—a re-imagining of the Song of Solomon. He skipped sports movies like When the Game Stands Tall, or the critically acclaimed drama The Good Lie (85 percent “fresh” on rottentomatoes.com). And that’s, what, about a third of the Christian movies that have been released nationally just this year?

Given that he chose one movie from 2004 and two others from 2014, he missed the entire Kendrick Brother oeuvre thus far (they were the guys behind such Christian movies as Fireproof and Courageous). He skipped Soul Surfer and October Baby. He might not have even heard of my favorite Christian movie from 2013 (Grace Unplugged) or my least (Alone, Yet Not Alone). He ignored movies that would’ve shared some of his criticism of some aspects of Christianity (the sincere drama Blue Like Jazz and the Christian parody Believe Me, to name a couple).

He certainly didn’t include movies that sorta straddle the genre line (like, in my opinion, The Chronicles of Narnia films or Noah), or movies with a clear Christian message that don’t ever fall into the Christian movie ghetto for whatever reason (The Book of Eli comes to mind).

Lyngar is free to dislike Christian movies, of course. But let us not pretend that all Christian movies come from some collective (and, in Lyngar’s view) fevered Christian mind. Some feel political. Some may drum up persecution. But others may simply want to tell the story of a blind football player or a rebellious daughter or a carpenter from Nazareth or a couple of talking vegetables. They may be improbable fantasies or gritty docu-dramas, cheesy-if-sincere melodramas or wacky comedies. The only thing they share in common is one basic tenant: Jesus saves. That’s a critique of Lyngar’s that, I suppose, will have to stand. A basic tenant of the Christian faith is that Christianity is, y’know, a good thing: We can assume that Christian movies will always embrace that.

As a one-time religion reporter for a secular newspaper (the very sort that, according to Lyngar, Christians must abhor), I’ve had opportunity to get to know this crazy patchwork thing we call American Christianity, and it is far from monolithic. Even evangelical Christians—so often considered by outsiders as some frightening, monolithic special interest group—are startlingly diverse. So it’s natural that Christian movies would be, too.

Toward the end of his article, Lyngar writes something I found particularly interesting:

It is important to note that not all Christians believe the warped ideology or hostility expressed in Christian moviemaking. My father-in-law, David Ashton, is a retired professor of religion and a current Christian pastor. He often calls me out when I try to lump all Christians together.

Perhaps it’s unfair, Mr. Lyngar, to lump all Christian movies together, as well.