Christian movies can be difficult for secular audiences to embrace. Sometimes it’s because of the acting or writing. They can feel amateurish and overwrought or just way too preachy.

But there are times that, even when most of the aesthetic pieces are there, they’re a hard sell for general moviegoers. Why? Because, simply put, the stories can feel just too good to be true—even if they are true.

Which brings us to Woodlawn—a fine piece of Christian craftsmanship that, in the end, might be just too earnest for its own box-office good.

Woodlawn, in 1,500 theaters nationwide as of today, is named after a high school in the heart of Birmingham. Back in the early 1970s, when much of the south was resisting segregation, Woodlawn was being torn apart by racial tensions. Fights between blacks and whites were common. The whole school was on the verge of being shut down.

But hey, nothing unites a southern community quite like football does—particularly winning football. “Winning fixes just about everything, doesn’t it?” one of the coaches says during a pep talk. But before the Woodlawn football team could save anyone, it had to find a savior of its own.

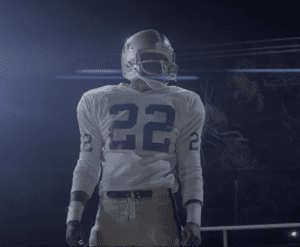

On one level, that savior is Tony Nathan (Caleb Castille)—a soft-spoken, ridiculously talented tailback who, as fate would have it, is black, playing at a mostly white school.

But the school also found THE Savior, according to the film.

After a difficult start to the season, head coach Tandy Gerelds (Nic Bishop) agrees to allow preacher/motivational speaker Hank (Sean Astin) to speak to the team for a few minutes. Hank ends up talking for an hour. “I am the way, I am the truth, I am the light,” Hank paraphrases Jesus during his pep talk. “And that means something to me, because I let it mean something to me.”

Before he’s done talking, something remarkable happens. As Coach Gerelds tells his wife when he drags himself into bed, “I let an untrained religious nut convert the whole team. I’m going to bed.”

The movie suggests that it was faith, as much as Tony Nathan’s skill, which made the difference. But Tony—a young man from a deeply religious family—was instrumental in helping to craft an environment where tolerance could take root and, eventually, thrive.

“You play for yourself, you can be great,” Hank tells him. “But when you play for something higher than yourself? That’s when something extraordinary can happen. … I think God wants you to be a superstar.”

Statements like that make me uneasy. Hank suggests that God cares deeply about who wins a given football game. “Nobody out there knows what’s happened with this team,” Hank says before a critical showdown. “But on this day, they will!” Losses are framed as God-given “tests,” which God uses to gauge the team’s commitment.

I think it’s dangerous to equate God’s blessing with secular success. I’ve known too many sincere-but-unsuccessful Christians to believe that God necessarily works that way.

But the movie, eventually, agrees. Tony’s success doesn’t just allow him the chance to go to the University of Alabama (and afterward, to the Miami Dolphins). It’s about being an inspiration to others. Woodlawn’s bitter rivalry with Banks High School is seen as the movie’s climactic moment—but it’s far more important that Woodlawn brought its own brand of faith to Banks than whether it brought home the trophy. “You know what’s more important than winning football games?” Coach Gereld tells Tony. “You are. You are.” And in context, that’s a message I can get behind.

Woodlawn is a great illustration of how far Christian moviemaking has come in the last five years or so. The acting is dandy, spearheaded by Castille, Bishop and Oscar-winner Jon Voight as Paul “Bear” Bryant. The directing and cinematography is strong enough to hold its own with the standard secular feature.

But the story itself feels a bit hokey and, at times, needlessly and uncomfortably political: The closest we get to a villain here is district bigwig Whitehurst, who dares suggest that maybe Woodlawn—a public school—shouldn’t be overtly proselytizing. If the ACLU had its way, the movie suggests, the whole state of Alabama would’ve just collapsed in an explosion of atheistic racial anger.

That seems a stretch.

But here’s the thing: As a Christian, I say that I believe what Hank does—that Christ can be the catalyst for amazing, life-giving change. When I doubt the ability of religion to change a school, and then a community, as the movie shows, am I knocking the movie? Or am I knocking my own faith?

Sure, Woodlawn’s story can feel a little hokey at times, a little convenient, a little too good to be true. But really, that describes the Christian faith itself to some extent, doesn’t it? In Jesus’ crucifixion, all seemed lost—until a miraculous resurrection saved the day … and us. It feels improbable. Too good to be true. And that’s why they call it the Good News.

As Christians, we believe in miracles. We believe that God cares for us. We believe in some amazing things. And maybe because of that, movies like Woodlawn—movies that feel too good to be true—will always have a tough time finding an audience outside a strictly Christian marketplace.

But then again, Woodlawn’s all about miracles. Maybe we’ll see a bit of one this weekend.