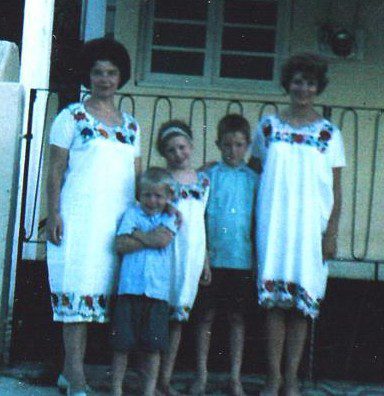

My father, a linguist, specialized in Mayan dialects. That meant that while growing up in Provo, Utah, I had a Mayan nanny named Hermana Yalibot. She always wore the same clothes: a white blouse embroidered with bright pansies, and a blue woven skirt. I now recognize her attire as typical of her region-Coban, Guatemala-and know that her skirt is called a corte and her blouse a huipil. She had embroidered the flowers herself. (Most areas of Guatemala have distinctive huipiles, personalized by the embroidery.) Hermana Yalibot also created bright flowers on some of my mother’s dresses, and surely would’ve stitched a magnificent blossom for me had I requested it.

She had a waist-length black braid, kind eyes, and a constant smile. I never spoke more than a few words to her, since she did not speak English, but I recall putting my head in her lap and feeling her fingers stroke my hair. I was six years old.

I was eight when my family went to Yucatan. I learned one Mayan phrase (Tu-ush-ka-bi’im” [“How are you”] and two Spanish ones: “Como te llamas?” and “Donde esta tu casa?” When my would-be playmates answered my questions with more than one word, I’d run to Dad and ask “What does it mean if they say…”

Poor Dad was working on a doctoral dissertation, and I was a too-frequent distraction. Though he urged me to “figure it out,” I simply couldn’t manage. It was all too alien.

My memories of that particular summer are not unpleasant. I remember doing cartwheels for the Indians of Xocampich, which would make them laugh and applaud. I remember swimming underwater in a moss-lined pool and feeling the slimy tile. I remember the excitement of watching an exotic red and black snake-a Coral-undulating onto our playground, where an Indian man whacked its head off with the lash of a willow. I remember getting sunburned so badly that my distraught mother railed, “Let’s take her to the hospital right now and get her skin grafted!” I enjoyed the attention, though I was oblivious to Mom’s frustration with the challenges and threats of a third world country and a relentless sun.

Not long after my biggest blister bloated into a half-inch bubble on my right shoulder, all of us but Dad went back to the U.S. He remained in the jungle with one mission: to analyze the Yucatec Mayan dialect and write the definitive grammar. He was delving deeper and deeper into that difficult world while the rest of us were pulling away from it. He was setting an example I would eventually try to follow.

When Dad came home to Utah, he brought Indians with him. The presence of Mayans in our household became the norm for me. There would always be someone in the next room who had dark skin and spoke a language I could not comprehend.

We did not return with Dad to Mayan country until I was nineteen years old. This time, the country was Guatemala, and by then, I had managed to idealize it.

In my imagination, Guatemala was the sort of paradise hippies were trying to build in their communes. I pictured acres of cornfields, fragrant red blooms the size of dinner plates, huge trees with monkeys and parrots in their limbs, and bronze-cheeked Indians who knew and loved the earth.

In Patsun, Guatemala, my fantasy stayed idealized for about a week. Maybe just five days.

I had not included fleas or mosquitos in my fantasy. I had not included diarrhea and the absence of flushing toilets. I had not included the emaciated, mongrel dogs or the unsteady, drooling drunks. Most of all, I had not included or even considered the frustration of not being able to communicate with anyone but my own boring family.

In High School, I had been a champion debater, orator, and actor. I had trophies all over my Provo bedroom symbolizing my much touted gift: to communicate, persuade, or just plain win an argument. In a competitive world, I had competed and won, and my skills had earned gilded awards. And now here I was, reduced to the very phrases I had learned at age eight: “Donde esta tu casa?” and “Como te llamas?” I couldn’t even pronounce some of the Mayan words, which seemed to thrust sound from the soft pallet.

I hated Patsun. Having known the glory of winning a judge’s “superior” rating for my speech, I hated being shrunk to silence, being stripped of the things which had won me all those trophies of winged, golden women holding laurels above their heads. I saw nothing winged in Patsun but predatory birds-and buzzards were common, indelicately eating the carcasses of dogs who hadn’t found enough scraps outside the butcher shop. Everything I was good at was useless here.

Dad, on the other hand, was in his element.

At age eleven, Dad had received a patriarchal blessing from his cousin, Alma Larsen, in which he was told that he had the gift of tongues and would be an “ambassador for the Lord in many nations.” For years, that prophecy had been coming to fruition, and now was really showing its meaning.

We went to Church in a very American-looking white chapel a few miles from Patsun, and Dad gave a talk. He opened it in Spanish, then said (so I surmised), “And now, if you will permit me, I would like to continue my sermon in Cakchiquel” (the local Mayan dialect).

Suddenly, the chapel was alive. Indian women who had been settling into sleep were startled from their dreams and began whispering. Indian men blinked and then stared at Dad like he had just announced the Second Coming. This was a miracle-a gringo speaking the language whose name literally means “our words.” A gringo speaking our words!

Cakchiquel is a dying language, spoken mostly by women who will never venture into the deepest circles of commerce. Their sons, after a meal, will repeat the traditional Buen provecho to their brothers and father, and then use the dialect to say the same thing to their mother and sisters: Ti-osh-u-oh. As Indians seek greater economic stability, they will move toward the urban centers, Guatemala City in particular, and often abandon their language in favor of Spanish. Some will even start wearing western clothing.

But here was an educated Gringo who not only spoke Spanish but honored “our” words.

Dad was on sabbatical and on assignment. He was going to teach the Mormon missionaries Cakchiquel. He hired a nineteen-year old Cakchiquel Indian named Daniel Choc to help him.

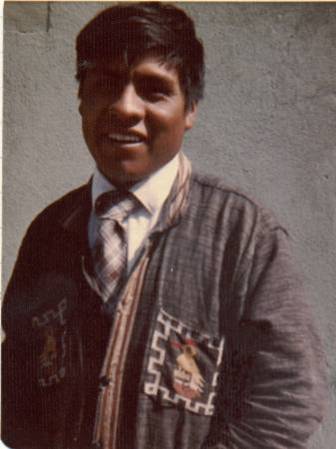

I can picture Daniel perfectly. He was joy personified-short, squat, and perpetually grinning. He laughed at the missionaries’ attempts to speak his language, but never mocked. And halfway through the training, Daniel received a call to serve as full time missionary. He would be the first Cakchiquel Mormon missionary. A new day had arrived, a day when the gospel would come not just from white Americans, but from one who knew the Cakchiquel people because he was one of them.

I went to Daniel’s farewell in that big white chapel where Dad had awakened the congregation. Though the chapel was the largest building after the Catholic cathedral, it could not contain all who had come to witness the event.

By this time, I was less resentful of Guatemala’s inconvenient poverty, and had learned a little Spanish and a few words of Cakchiquel. I understood most of what Daniel said-that the gospel offered a way of life which would keep families together and bring them to God, and that he was eager to serve. I was touched by his sincerity and by the love in that chapel, though I was not yet consumed by love. I still hated fleas and mosquitos, and I remained frustrated by my limited language.

The event that would bind me to Guatemala and knit my heart to the hearts of the Cakchiqueles was still ahead.

It began one evening when only my brother and I were at home. A missionary (Milo Garcia)stopped by to ask if we would like to visit the home of the first Mormon convert in Patsun: Tomas Cujcuj. Hermano Tomas had joined the Church some fifteen years before. He was an old man now, and he was dying.

My brother and I walked down the dirt road, up the main street’s cobblestone, then down another dirt path to a bamboo gate which led to Tomas Cujcuj’s adobe dwelling. That unlatched gate would invite me to a new life, though I certainly didn’t know it then.

By the time we arrived, it was dark. There was no electricity in that part of town, but the hut was full of Cakchiquel Mormons holding candles. Inside smelled of bamboo mats, wet mud, and melting wax. The women all wore similar clothing-hand-woven, red huipiles to which they had added their own embroidery. They all had long, braided hair. Some wrapped their braids around their heads and some wore them down. Some braids were black; some were silver. The men, including the one who was dying, were dressed in white.

Hermano Tomas, wearing a knitted cap, lay on a bed which took up nearly half the space in the hut. His skin looked sallow even by candlelight. There was no question that he was dying. Weakly, he requested hymns, and the Indians sang. My brother and I used hymn books. Spanish was not native for anyone in that hut, but we all sang the words.

Cantemos, gritemos

Con huestes del cielo

Hosanna, hosanna a Dios y Jesus

A ellos sea dado loor en lo alto

De hoy para siempre, amen y amen…

In Utah, I had had voice lessons, and could have made my music soar. But that simply would’ve been wrong in this setting, and I knew it. This was not the time for any one voice to stand out. Though the Indians sang off-key and mispronounced the words nearly as much as I did, unity was what mattered. We were together, all poor and afflicted in some ways, all rich and blessed in others.

Using a battery-powered projector, the missionaries showed a filmstrip of “Man’s Search for Happiness” above Tomas Cujcuj’s deathbed. The pictures were grainy against the adobe. I had seen the film (where the images actually moved) many times at Temple Square, but had never felt the reverence I felt that night. Then the missionaries asked Hermano Tomas if he would like to bear his testimony. He answered in Cakchiquel: “Ha.” Yes.

I did not understand a word he said, but felt a swell of love and awe. Who was this man who lay dying before me? In a rush of revelation, I became aware that God knew him intimately. I could feel God’s love for him, for it permeated the hut. It must’ve permeated all of Patsun; surely it was too strong to be contained within one room. I knew there were angels in that poor, adobe hut where Indians, missionaries, and two red-headed gringos sang hymns by candlelight.

Tomas’s conversion, I later learned, had resulted in many Cakchiquel families listening to the missionaries, for he had been the town mayor when he joined the Church. The night before the elders first visited him, he had dreamt of two messengers who would bring him words he must heed. I learned that he and his wife had saved up money for a year so they could take a bus to Mesa, Arizona and be sealed in the temple. I learned that in his last testimony, which I heard but did not understand, he had said, “I know I will go directly to my Lord Jesus Christ.”

My brother and I left the hut a few hours before Hermano Tomas died. Because of the twenty-four hours burial laws in Guatemala, funeral arrangements were hasty. Of most urgency was getting temple clothes from Guatemala City to Patsun so that Tomas could be appropriately robed in his coffin.

The missionaries invited me to play the organ at his funeral, the organ being a plug-in keyboard which wouldn’t make a sound without electricity. But when I walked into the chapel ahead of the funeral procession, there was no electricity. No light. No luz.

I ran to the office which controlled Patsun’s power. The door was locked. I ran back to the chapel. I prayed. “Father, please let there be light. Let there be light in this chapel so I can play music for your son, Tomas Cujcuj.”

I waited.

Nothing happened.

I prayed again. Once more, I ran to the power office. It was still locked. I ran back to the chapel and touched the organ keys to see if God might grant me a miracle of sound without the electricity to power it.

Nothing.

Then the chapel doors opened. Six men were holding Tomas Cujcuj’s coffin on their shoulders. They stepped into the chapel. Instantly, the lights came on. I closed my eyes, said a quick, “Thank you” to God, and then sat down at the organ. I began playing “Behold the Lamb of God.”

Behold the Lamb of God

Behold the Lamb of God

That taketh away

The sins of the world

Surely, I was one of the sinners dependent on the Lamb’s grace, sinful in my pride and in my selfishness. But I was also one of the blessed-so blessed to be able to play Handel’s music at the funeral of this great man. As the chapel filled, I realized I was surrounded on all sides by greatness.

The Indian men wept freely; they have not been taught to conceal their emotions. The women groaned in grief. The swell of love and recognition which had begun the night before continued. I loved them completely, and recognized that I was the least of them. I thanked God for their mercy. I thanked Him for their patience with me, an arrogant American teenager who had mangled their language and had refused to open her heart fully to them.

That was 1975. My family returned to Utah in May, moving from the mists and canyons and adobe huts of Guatemala to the mountains and well-wired condominiums of Provo.

The next February, around midnight, Guatemala was hit by an earthquake, the epicenter only a fifty miles from Patsun. Twenty-two thousand people-mostly Cakchiquel Indians-perished as their adobe collapsed around and on top of them. Daniel Choc’s pregnant mother was among the fatalities, as were two of his sibling.

A month after the quake, Daniel and other Mormon missionaries were helping with the reconstruction of Patsun. He was standing on a roof when it collapsed. He died within fifteen minutes. One of the missionaries Dad had trained in Cakchiquel, Elder Warnock, took Daniel’s body, covered by a sheet, to his father, Pablo Choc, in nearby Patzicia.

I received the news of Daniel’s death while living in Denver. The next year, I returned to Guatemala and visited the ruins of Patsun, as well as Daniel’s gravesite.

The Indians bury their dead in colorful crypts like thin mountains. The coffins are placed and cemented, one grave on top of another. It’s a highrise of death.

Daniel’s grave, however, was not a part of the mountain. His was set apart. The missionaries had all donated money for this particular memorial. His grave, the size and shape of a refrigerator, was painted white and bore a headstone engraved with a gold-leafed Angel Moroni and a scripture: “Cuando os halláis en el servicio de vuestros semejantes, sólo estais en el servicio de vuestro Dios.” When ye are in the service of your fellow beings, ye are only in the service of your God.

I returned to Guatemala three times afterwards, and witnessed the destruction an earthquake can unleash. Piles of rubble had replaced the house my family had lived in. Even the Catholic cathedral was reduced to boulders and pebbles. But the Cakchiqueles were continuing their lives in quiet dignity. Both times I returned to Guatemala, I lived with Indians in new-built huts. I slept on a mat, made tortillas on a comal, sang Cakchiquel lullabies to children, and eventually adjusted to the fleas and mosquitos. Following in my father’s footsteps, I always enjoyed going to the market and surprising a vendor by asking a Cakchiquel question. I continued to be amazed by the easy joy the Indians showed, by their meek and noble lives, and by their gracious customs. I recall one night being awakened by a knock on the door. A cousin of the family I was staying with had brought bad news. Tia Josefina was ill and wanted the family around her. That was all the invitation required. Everyone was up and ready to go to Tia Josefina. Little did I know she lived a mountain away. That was simply how they did things in Patsun. They constantly allowed themselves to be happily inconvenienced for the sake of a loved one. I walked five miles to a birthday party once, along with my Cakchiquel brothers and sisters. Nobody considered the trip anything extraordinary. Just as “Cakchiquel” means “our words,” these common acts of grace meant “our ways.”

In 2005, I took two of my children back there. I introduced them to Daniel’s father, Pablo, and told them he was “one of the great men of this earth.” My children watched me speak with him, just as I had watched my father speak with the gente indigena , and watched us weep together. I hope they treasure that memory.

We all taught English at a school in Patzicia. As our time there ended, my daughter paused on the path and said, “Wait. Let me feel the love.” Yes, they felt the wonder of unencumbered love and clock-free devotion. Would that we all could feel that love and then serve as the Lord would have us serve-using whatever gifts He has given us, and openly receiving the gifts which others provide. That’s the design. The pattern is set, and the loom belongs to God. We simply add our own embroidery and accept the thread and flowers offered by others, seeking-in all our ways-to acknowledge Him.