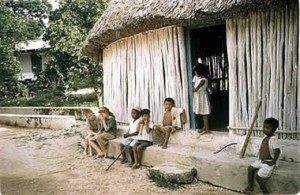

This beautiful essay is by my brother, Dell Blair. Dell and I love Central and South America. Dell speaks Quichua and Spanish. Our siblings tended to go more to China. Dad went everywhere. This is one of the great Blair legacies. We do not tour. We root ourselves in places and people. Dell’s essay shows it so movingly.

Amado Maldonado.

Shoulder deep into the dark soil the shovel tip snagged the edge of another casket.

“Good,” said Rafael. “Dig to the end and down. Just make a little space.”

“Do you know who this is?” I asked, knocking the exposed wood with the shovel.

He stepped over the pile of freshly tossed dirt, slid the right half of his poncho over his shoulder and gathered the box under his arm and said, “My wife.”

The casket he held was small and fragile. It had been crafted by the child’s father and some men from the Otavalo branch on the patio of the Maldonado’s dwelling. While the men sawed, joined and nailed the casket pieces the women and mother washed the child’s body and wrapped him in soft white wool.

The men’s work was solemn but routine. The women’s labors were rituals of such concentrated sorrow that it seemed nature itself gasped when the mother, overcome with emotion, hugged the body of her child to her breast, looked to the heavens and drew in air. There was no other sound, just her deep penetrating breath, and every eye and every heart fixed upon her, too startled to cry or think or move. We just inhaled and in that moment we were perfectly joined in our sorrow and in our loss and in our love and in our breathing.

We were the morticians; and the Maldonado’s patio was our mortuary; this was a gritty visceral reality with no institutional buffering or making pretty. There was no one else to do the work we shared. I was the grave digger.

Rafael reached the coffin down to me and hopped into the hole.

In Otavalo we were not allowed to use the city cemetery because we were Mormons. So our burials were on a hill overlooking the valley at the base of Taita Imbabura, a volcano less than twenty miles north of the equator. In the coffin was the body of Amado, a boy not yet six months old. Rafael placed it gently on the floor of the tomb and scratched it back and forth into the soil so it grounded without tipping or rocking. He stood and stared for a moment at the other coffin.

“Did you know my wife?”

I shook my head.

“She was good and very beautiful.”

“When did she die?” I asked.

“Oh it has been four or five years now. Of course you wouldn’t have known her, you just came last year. She was sick. So was I, and I died too for a while.”

“You died?” I asked.

“Well, I went to heaven. It was beautiful, peaceful. I had to come back. That’s where I heard the choir.”

Rafael was the second branch president in our struggling congregation and one of only a few members who could read. I played the piano and asked him once why he had us sing Redeemer of Israel so often. We sang the hymn not just every week but, to my recollection in every meeting every week. He told me about the choir.

“When I was sick and died once,” he said. “I went to heaven and wandered around alone. I could hear beautiful music in the distance and walked toward it. I came to a stone wall and followed it until I arrived at an opening. When I stepped inside I saw the music was from a choir of heavenly beings dressed in white robes. There were no songs that I recognized, but the music of one was so beautiful and so moving that I cried even though I did not understand the words. It stayed in my mind. I heard it in my dreams. When I was learning about the restoration I went to a meeting and the first song we sang was Redeemer of Israel. That was the song I had heard the choir in heaven sing.”

A drift of clouds crossed the hill and wrapped us in its mist.

As we spoke we could hear a soft conversation of women’s voices approaching. When we looked up two women stood above us in the drifting fog. One of them said something I did not understand to Rafael, and they began to sing and play a small drum.

“Who are they?” I asked.

“They sing for the dead,” said Rafael. “They sing to guide them home.”

They were a mother and daughter dressed in an ancient style I had seen only in photographs.

Rafael climbed out of the grave and stood by the women while I packed soil around the coffins.

This is how they cared for each other. The mother and daughter were the only ones left in their family, and this was their work. The mother wore layers of different colored cloths topped with a red wool blanket that almost touched the ground which she fastened across her chest with a silver safety pin. Her hair was almost completely white with hints of fading gray deep in the underlayers. She wore a light hat which hugged her brow. It had a loose brim that drooped over her ears. Her smile disclosed only her lower teeth with gaps where most were missing. There was an intensity to her singing and a simple beauty in her voice. She and her daughter sang the mostly monotone melody and when they had finished the song brought out a bowl of live snails which they offered to us. We ate, gave the women some coins, and began the task of filling the grave with soil.

After a few shovels full I paused with the handle trembling in my hands. I just stood there staring at the caskets we were covering.

“How can you stand this?”

Rafael continued working and kept his emotions calm. I daubed my eyes on the shoulders of my shirt.

“You’ve lost how many children and your wife. The Tabangos have lost eleven. How can you stand it?”

“We can’t stand it,” he said, his voice cracking. “We can’t stand it…not alone. And that is why you are here. And that is why I’m here. The weight is unbearable. And that’s why God is here. We are afraid that this is it, that this is all there is, that this person I love so much is gone, not just for a moment or a season but forever. And I can’t stand that! So God speaks to me and says, ‘Rafael, don’t be afraid’ I am with you. Don’t be depressed; you are my child and I am your God. No matter how great the weight or how massive the burden that pushes down on your soul driving you to your knees or your chest or your face, I will strengthen you and I will help you and I will cause you to stand. I will hold you up even by my own hand. That’s from hymn, but it is real. It has happened to me. I have felt it. I have lived it. It is not just a song, not just a scripture.

“You are his hands here. You and I are his hands right here. We are God’s hands bearing the burdens of the Maldonados and the rest of us who weep and over the loss of loved ones and can’t stand the burden of their absence. Whatever we can do we have to do. That is how we serve God. You know that. That’s why you are here. That is how we stand it.”

When the graves were filled and the sky had cleared we walked silently back to town with our shovels over our shoulders. Taita Imbabura was bathed in gold in the light of the setting sun. As we entered the city the Maldonado family met us. We shook hands, embraced and cried until the sky had filled with stars.