April 1, 1949: My dad is taking a shorthand class at BYU. His sister, Carolyn, appears at the class door asking him to come out. He hesitates because he’s not yet finished with the assignment. She beckons more urgently. When he steps into the hall, she says, “Bobby, Daddy has died.” They go to Santa Barbara, their hometown. My grandmother has been put on tranquilizers. Grandpa had died of a heart attack. Dad takes care of funeral details and late at night, goes to the mortuary, where he sees his father in the coffin. He breaks down.

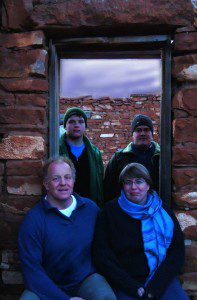

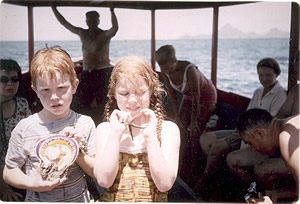

My brother and I have red hair, like our grandpa Blair did. Dell looks a lot like him. Yesterday, April 3, my sister called my parents to tell them that Dell had gone into cardiac arrest and was in an induced coma at the University of Utah hospital. Mom and Dad held each other and wept. Another brother, Jim, drove them up to the hospital. When I got there, I embraced Dad, who held me tightly and cried, “He’s going to live. It was like seeing my father in his coffin. But Dell will live.” Dell was still in the coma, but was starting to come out.

Dad and Jim had given him a blessing. Jim had promised him a full and quick recovery. Whatever the arguments are about who is or is not ordained to the priesthood, the intimate moment of my father and my little brother laying their hands on Dell’s head is a picture of what I cherish about priesthood blessings–the love of family members, faith in the future, appreciation for life, connection to the divine.

When Dell and I were children, people asked if we were twins. We told them that I was the older (by one year), but the truth is, we are twins in many ways. We are both prone to live in various countries and learn new languages. We are both creative but not well-organized. We are both fearless about trying new things. Dell discovered that a college would be throwing away its windows during remodeling, and asked if he could have them. He then built a greenhouse in his back yard. He took up painting and has now painted portraits of all of his nieces and nephews–and of my grandchildren as well. In February, when I needed a prop for the play I Am Jane, I asked Dell to make it for me. He left me a voice mail message: “Margaret, the coffin is in your living room.” (Yes, the prop was a coffin.)

Dell would simply show up at someone’s house if he knew they needed help. Once, while home teaching, he felt he should drop in on an ex-Mormon. He did, and they had a good chat. Then the ex-mo showed him some chemicals and pills laid out on her coffee table. “I was planning on taking my life tonight,” she said. “I guess I won’t do that.” Another time, he saw an old friend on a bus. The friend was smoking, and apologized for it. “I try to quit,” he said. Dell held out his hand and said, “Why don’t you quit now. Could you give me the cigarettes and I’ll dispose of them for you?” The friend obeyed.

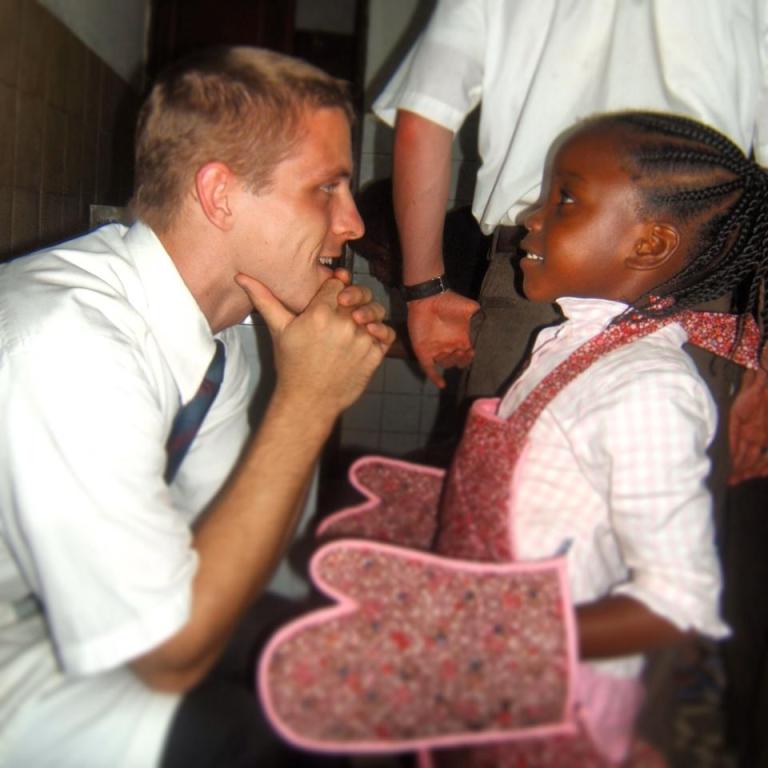

Dell served a mission to Ecuador and learned not only Spanish but Quichua. He wrote this about a funeral in Otavalo:

The casket he held was small and fragile. It had been crafted by the child’s father and some men from the Otavalo branch on the patio of the Maldonado’s dwelling. While the men sawed, joined and nailed the casket pieces the women and mother washed the child’s body and wrapped him in soft white wool.

The men’s work was solemn but routine. The women’s labors were rituals of such concentrated sorrow that it seemed nature itself gasped when the mother, overcome with emotion, hugged the body of her child to her breast, looked to the heavens and drew in air. There was no other sound, just her deep penetrating breath, and every eye and every heart fixed upon her, too startled to cry or think or move. We just inhaled and in that moment we were perfectly joined in our sorrow and in our loss and in our love and in our breathing.

Dell had told us, his family, about that single breath which everyone took in unity, that audible connectedness. He yearned to find it throughout the world. His full essay is here.

The call I got yesterday to inform me of my brother’s condition was not frightening. I never thought he would die. He was in good hands. Besides that, I knew the world would have to stop if Dell weren’t in it. Wouldn’t it?