The Real Elder Price

The “Real” Elder Price, Part 1: The Missionary Training Center

My husband and I spent two years in an MTC branch — where we met the “real” Elder Price and various “Mormon boys” on the first day of their missions.

By Margaret Blair Young, December 08, 2011

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author’s Introduction.

The Book of Mormon Musical opens with a scene of Jesus, Mormon, and Moroni on Hill Cumorah in upstate New York. It is a brief and campy depiction of a Mormon theophany, something which appears absurd and laughable to many: the idea that gods and angels would be personally involved in burying gold scriptures. In many ways, it plays on a central Mormon tenet—not just the belief in the prophetic calling of Joseph Smith as translator and restorer, but the belief in continuing revelation. Such revelation not only makes seers of farm boys, but suggests that Jesus Christ and other Heavenly beings are present even in the most unlikely places, and that every human being can be spiritually enlarged beyond any border which mortal paradigms impose.

Mormonism itself demands a generous imagination. We Mormons are urged to imagine one another’s potential with limitless generosity, daring to believe that the most lowly, uncomely, unrefined person is potentially as glorious as any divine being represented with ultra-watt lighting on a Broadway stage. The Mormon imagination is telescopic, inviting us to see far into the distance, beyond time; to look into the Heavens and imagine that—even in the presence of such mind-boggling creativity as the stars and planets manifest—we humans and our incomprehensible future are God’s “work and glory” (Moses 1:39).

| Elder Price’s name badge |

So, these divine beings in upstate New York do make a central statement about Mormonism and imagination. If viewed cynically, the suggestion that anyone might actually believe that gods and angels would behave so unexpectedly (or behave at all) appears simply naïve. Taken representationally, the scene implies (accurately) that we Mormons are accustomed to dealing with the unexpected, that we allow ourselves to be surprised by grace in many ways and places, that we don’t “just believe,” as one of the show’s songs states, but that as we grow in love, we behave as love itself does. And love (says Paul) “bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (1 Cor. 13:7-8). It’s not so much a habit of “making stuff up again” (as another show song claims) as it is a willingness to nurture glorious “what if’s.” Love persuades us to view ourselves and our brothers and sisters—comprising everyone—in the light of eternal prospects, granting the potential for individual and communal progress. This progress doesn’t end. We Mormons don’t believe in an either/or (Heaven or Hell) judgment immediately after death. We believe that as God’s children, we may continue to learn and grow even after our earthly lives end. The only thing that prevents growth is a personal option for stasis.

That there are naïve Latter-day Saints is beyond question. That there are Mormons who don’t understand the hierarchy of gospel principles, and assume that a belief in Kolob is equally important to faith in Jesus Christ, is true. But globalizing and reducing all Mormons to the stereotype of smiley, gullible replicas of each other is using imagination as a flat iron rather than a telescope.

The protagonist of The Book of Mormon Musical, Elder Price, doesn’t appear until this Hill Cumorah tableau fades, and then, he’s already a missionary.

The real Elder Price, as presented in this series of essays (Elder Brandon Price), agreed to imagine himself and others with a divinely generous imagination when he was ordained to the Melchizedek priesthood. In that moment, he was told that he now held “the keys to all the spiritual blessings of the church” and that he could “have the heavens opened . . . and enjoy the communion and presence of God the Father, and Jesus” (Doctrine and Covenants 107:18-19). His temple endowment magnified his godly imagination. He entered the temple in his Sunday clothes, and carried a bag that would change his life. In the bag were new temple garments. For the rest of his days on earth, he will wear this “Mormon underwear” as a constant reminder of his consecration. The depiction of garments in The Book of Mormon Musical predictably gets a small laugh—and you can almost hear the audience members whisper, “Oh of course! Magic undies!”—but we Mormons take our garments seriously. As much as a yarmulke or a priest’s collar indicates personal commitment in other religions, garments, for us Mormons, serve as symbols of our promises to God.

When the Broadway audience first sees Elder Price, he is in the Missionary Training Center (MTC), and soon meets his socially inept companion, Elder Cunningham. These two, with the “Mormon Boys” (various other missionaries), practice a door approach with repetitions of the enthusiastically sung “Hello.” The music is fun and catchy. The MTC experience portrayed on stage is, however, nothing like the real thing.

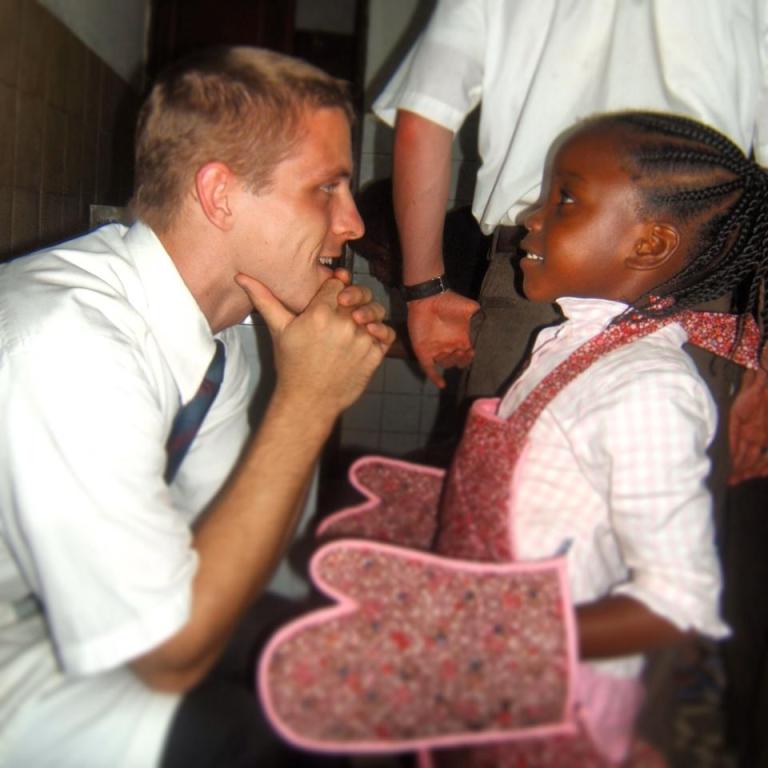

| Elder Price at MTC |

My husband and I spent two years in an MTC branch—where we met the real Elder Price and various “Mormon boys” on the first day of their missions.

I wrote this about our experience on May 22, 2008:

Yesterday evening, Bruce and I welcomed twenty-one missionaries into our branch at the MTC.

Several of the missionaries come from blended families, where death or divorce has ruptured expectations. At least one young man delayed his mission for a year until he could work through the issues his mother’s death had introduced. One missionary was from Scotland. When I shook his hand, I noted his plaid tie. “It’s not my tartan, but it’s a good one,” he said in a thick accent.

I answered, “You’re from Scotland, aren’t you. Either that or you’ve mastered the accent.”

“I’m from Scotland.”

“Well, you have a very good accent.”

“Thank you very much,” he said. “I’ve been working on it for eighteen years.”

Most of these new missionaries have sung “I Hope They Call Me on a Mission” since they were old enough to carry a tune. But there are exceptions—some who had not considered a mission until recently. One, a musician, gave up an orchestra tour which included Carnegie Hall so he could serve. Another was in a rock band and had the opportunity to do a European tour. He had to choose between that tour and a mission. He sold his guitars. His mission was financed by the money those guitars brought in. One—Elder Jared Wigginton—already had a college degree focusing on international relations, and even taught for a year. He was admitted to law school, and chose to defer his admission for two years. He will be going to Africa. I am eager to see how this mission prepares him for the rest of what he’ll do in his life. He will learn about Africa in a way no class on international law will ever teach him.

Elder Brandon Price would enter the MTC four months after Elder Wigginton.

Brandon had submitted his mission papers a few weeks before his “call” came in a large white envelope. (No, mission calls do not happen in “the Center” as The Book of Mormon Musical depicts.) Brandon sat on the couch with a knife and the envelope.

“Okay, any last minute guesses?” he said, already sawing the envelope open.

“Some place European! Tennessee! Canada! Guatemala!” his family shouted.

The envelope was opened, and he lifted the papers out. He stared at the top one.

“Read it out loud!” his mother coached.

“Wow,” was his response. He had already seen it. “Dear Elder Price,” he read, “you are hereby called to serve as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” his mother breathed.

“You are called to labor in the D.R. Congo-Kinshasa mission.”

A gasp and a chorus of “What?” interrupted him.

“You’re going to Af-reek-ah!” his father yelled.

“I’m going to the Congo!” He continued reading: “You will preach the gospel in the French language.”

“Are you joking?” his mother asked.

“No!” He stared at the call. “I never heard of anyone going there.” He read further: “It is expected that you will labor for a period of twenty-four months.” As his sister tried to find the Congo on a world globe, Brandon Price repeated, “Wow. Wow.”

“Wow,” his mother echoed.

(Other Africa-bound missionaries had different responses from their families. One had a grandmother who started crying, “You’re going to die!”)

| Elder Price with map |

On Wednesday evening, September 24, 2008, my husband and I met Elder Price. He was wearing a new suit, new shoes, and a new missionary badge with a little red dot, identifying him as just-arrived. During orientation, the “just-arrived” removed those dots, and the branch president introduced them to their texts: the scriptures and Preach My Gospel, which gives instructions on how to teach, but more importantly on how to develop Christ-like attributes.

Elder Price was paired with Elder Seth Lee, from Seattle, who was also headed for the DR-Kinshasa mission.

| Elders Price and Lee by Provo Temple |

We asked each missionary to tell us a little about their lives thus far.

Brandon Price had been a student at Dixie State College, studying theater. He believed in the gospel and wanted to share it. Of course, most of the missionaries are fulfilling family expectations, but such expectations are cumbersome when the real work begins. As the president of the MTC once said, “It doesn’t matter what got you here. You might be here because your girlfriend said she wouldn’t marry you if you didn’t go on a mission. You might be here because your father promised you a car. All that matters is that you’re here. And now, if you do your part, you will become a disciple of the Lord.”

Some missionaries have agonized over the choice to serve—two years far from home, and at their own expense. One, older than most in the MTC, reflected on his decision in these words:

It was at the invitation of a friend to pray and fast about it that I really began to explore the possibility of going on a mission. I remember having dinner prepared and leaving it on the table to go up to my loft to pray. The Lord had chastened me. He had taken away the things that I was hanging onto, and when there was nothing left (or so I felt) I was in that oh-so-familiar place: kneeling next to my bed, saturating my comforter and sheets with my tears and pleas to Heavenly Father. The direction became clear.

I talked with my Bishop. I went through heart-wrenching moments, acknowledging and sharing everything. I remember the difficulty and the love. I remember the anxiety and the peace. And the day I knew a mission was a real possibility, I made a decision. I did not do it for my mom or dad; I did it because I knew it was right for me, that I had to make sacrifices; that if I did not do it, my life and ideals would amount to mere words. I had been given the opportunity to truly contribute to the welfare of the world by serving Heavenly Father’s children one by one.

Most of the MTC elders are still in their teens, so such introspection is not the norm, and childish antics are not uncommon. Elder Price wrote in his journal: “I do get a little frustrated some days with the immature high school-ness of some people, but that’s okay and normal, I guess. The MTC really isn’t that horrible.”

| Elder Price in MTV |

Though they will still behave like the teenagers they are, most of the missionaries find themselves praying with new intensity as they begin this mission they’ve been planning for so many years. Elder Price’s companion had simple counsel for him: “Lighten up.” Indeed, Elder Lee, with a gift of humor, would always honor serious things as a missionary, but would be able to crack a joke when the tension got too much.

Tension could get particularly thick during language classes.

| Sleeping missionary in language class |

Our missionaries were all learning French, and were expected to develop at least some fluency within the two months of their MTC stay. Toward the end of his two months, Elder Price wrote to his family: “I’ve been freaking out about forgetting all my French, but apparently I’m doing something right, because the other night, one of our new roommates told me that I was talking in my sleep in French. So something’s getting down into my brain somewhere.”

Elder Henry Lisowski (who arrived three months after Elder Price) wrote to me about how hard the language had been for him in those classes. “You’ve probably heard of the struggles I had with French,” he said. Yes, he thought his ineptitude was legendary.

My husband and I got to spend two months with our missionaries before sending them to their various mission fields. We welcomed, supported, and then said good-bye to them. Those farewells were often emotional, as I described in this note:

| Elder Price with district in language class |

On Sunday, our MTC Branch President will ask the departing district to stand. He will say, “These missionaries will be leaving tomorrow. We want to thank them for their service in our branch and we certainly wish them well on our missions.”

They are such good kids—so pure and full of hope. Some have done very well with their French; others are still struggling. And just wait until they hear how it’s really spoken! They have no idea how difficult and how precious the next twenty-two months will be for them.

And then they were gone to the countries they had been called to. Elders Price, Wigginton, Lee, Lisowski, Coburn, Parsons, and Kesler were all headed to the same mission in Africa.

The Real Elder Price

The Real Elder Price, Part 2: Welcome to Africa!

When a young man is ordained to the priesthood, he is, in many ways, initiated into Mormon manhood.

By Margaret Blair Young, December 12, 2011

Total time from the wheels leaving the runway in Salt Lake City to touchdown in Douala, Cameroon: 23 hours 15 minutes and 9 seconds. Not too bad, but definitely tiring.

Thus wrote Elder Brandon Price of his flight to Africa.

The arrival in Douala was the biggest shock of my life. When I walked out of the plane, I was drenched with pure humidity. It is really hot.”

Since he arrived on Thanksgiving Day, the senior couple (the Bakers) had prepared a Thanksgiving feast for him and the other missionaries, and so he had a pleasant culinary welcome. Such was not the case for other missionaries. Elder Jared Wigginton described some of his early meals vividly:

| Missionaries at sunset |

The food is hard on my stomach and literally hard to swallow. I have tried to be a good sport, but I could not swallow the cow skin. I was, however, able to swallow monkey and its skin yesterday, and now I am sick with fever and a pounding stomach ache. My first day here, I accidently put a chicken head on my plate. Needless to say, it is a delicacy and it would have looked really bad if I did not eat it. Fortunately, Elder Anderson, whose praises will be sung by my posterity for generations to come, switched his chicken neck with my head without anyone seeing. As he bit through the skull, brain juices flooded down his mouth, I shuddered and sang for joy at the same time.

Yet, being deprived of American food for so long and being hungry from the hours and hours of marching in the blazing heat, I actually have not turned down a meal. Strangely, fish heads in peanut sauce with rice is not so bad; couscous with gumbo is appealing; and manioc with green-mushy-i-do-not-know-what-you-are-made-of is delicious. If the fact that I can eat this food is not evidence of the Lord’s blessings, I do not know what is.

Regardless of what the missionaries ate for their first meals in Africa, the work expected of them was the same: They would walk, talk to potential converts and LDS members, do service projects, and teach.

| Elder Brandon Price and Elder Lyle Parsons walking |

In the heat and humidity, to which the Anglo missionaries are so unaccustomed, the reality of missionary work can be overwhelming. They learn quickly that they have lived in luxury for all of their lives, and things they take for granted (carpeting, dependable electricity, clean water) are rare in Africa. Spiders as big as a toddler’s hand periodically scramble up the walls, and the missionaries’ beds are surrounded by nets to protect them from malaria-bearing mosquitoes.

The whole experience can bring even an Eagle Scout to his knees.

| Mosquito net |

Elder Kendell Coburn, who arrived in Africa three months after Elder Price, found himself praying in the apartment’s little kitchen early in his mission:

I was thousands of miles away from home, homesick, unable to express myself in French, starving (I didn’t dare eat anything), and stressed. I decided to pray. In the tiny kitchen I said my prayer and all doubt left. An overwhelming peace replaced it. It was reaffirmed to me that the gospel was true and that I needed to stay, that I would cherish my mission, influence very many people, and would one day miss it.

Elder Price’s first week as a missionary in Africa was typical:

There aren’t addresses or roads in the slums where we teach, just narrow dirt paths and open sewers. I’ve forgotten all the French I learned and I am a little shell-shocked. And I walked. A lot. I had to have walked at least thirty miles this past week. My calves are looking killer. And really, really white.

| Elder Kendell Coburn |

Besides all the walking, Elder Price arrived in Yaounde, Cameroon in time to help with a demanding service project: cleaning and refurbishing an orphanage. Missionary labor is often simply labor.

There would be other service projects as well: cleaning a prison, painting a school, and working on wells.

Elder Price’s first companion in Africa was a Canadian named Andrew Kay. Missionaries, as The Book of Mormon Musical recognizes in a song, go out “two by two.” They are to protect and support one another. They also begin acting as ordained ministers—baptizing, preaching, and using “the laying on of hands” to heal or bless.

The lay priesthood is a distinguishing attribute of the LDS religion. Nearly every active Mormon boy is ordained to the Aaronic priesthood at age 12, which is comparable to a Jewish boy’s Bar Mitzvah. The family celebrations in Mormonism are not as festive as those surrounding a Bar Mitzvah, but the newly ordained young man will begin serving in priestly duties, including administering the sacrament. When he is ordained to the Melchizedek priesthood, prior to his mission, he is, in many ways, an initiate into Mormon manhood. Shortly before to his departure, he will be “set apart” by a Church leader. All of his time and energy will be dedicated to God for the next two years. He is tithing his life. He will pack up and put away the emblems of his youth: iPods, skateboards, computer games.* His life has been ordained, or put in order, for a particular service and a designated time.

| Missionaries working at “Green Eyes for Africa” orphanage |

Within a few months of settling into his new life in Cameroon, he performed his first baptisms.

In The Book of Mormon Musical, Elder Cunningham sings “I’m going to baptize you!” as he prepares to immerse a beautiful Ugandan woman, Nabulungi. The song is rich with sexual innuendo.

There was no such innuendo when the real Elder Price had his first experience baptizing a convert. He baptized two women on that day, both much older than he: Louise and Sidonie.

Louise was late for the service, having just discovered that her purse had been stolen. Without the purse, she had no money, not even for a taxi. So she walked three miles to get to the church.

Elder Price baptized Sidonie first. He descended with her into the font. As he said the words, “Having been commissioned of Jesus Christ, I baptize you in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost” and then immersed her, his MTC companion stood at the font’s side, witnessing.

| The dedication of a well in Pointe Noire, Republic of Congo |

“The weather for the baptism was perfect,” wrote Elder Price, “but as we started to say the closing prayer, there was a huge downpour. It was one of my first tastes of what the rain can do in Africa.”

Just as he was learning about baptism (a ritual he would perform many times in his twenty-two months in Cameroon), he was also learning his first lessons about rain—African style. He would become an expert, as would all of the missionaries.

Elder Wigginton wrote this in a cyber café, as torrents of rain bulleted into the dirt roads outside:

Wow, I just saw a huge bolt of lightning. It must have been close because a loud crack, and rumbling thunder immediately followed. We really get thrashed out here after the rain. The mud is sticky, and red. The other day, I honestly carried about three pounds of mud between my shoes. The funny part is that as I walked up and down the quartier, the foliage and trash I could not avoid stepping on would cling to the mud. I would have plastic bags and long pieces of grass dragging behind me. Fortunately, many of our investigators’ family members wash our shoes off for us while we teach. There is a lot of love that we receive between the insults (which I am starting to understand better).

| Elder Seth Lee witnesses Elder Brandon Price perform his first baptism in Cameroon |

Yes, they would learn about rain—and about poverty, and love, and friendship.

Elder Price would not meet his future friend, Elder Wigginton, for several months, since “Wiggs” had been transferred to Pointe Noire, along with his new companion from Zambia, Elder Chiloba Chirwa (known as “Chills” outside of his mission life).

It was Elder Wigginton who first wrote to me from his mission, letting me know that, given the undependable mail system, missionaries were permitted to email friends as well as family. Thus began my adventure of sharing the missions of several young men we had known in our MTC branch. Soon, I included their companions on my list. Ultimately, I wrote to twenty.

Elder Wigginton introduced me to Elder Chirwa via email. I assumed that this African missionary was a Francophone, and so asked “Wiggs” to translate a message to his companion. I also assumed Elder Chirwa knew nothing about the world outside of Africa, that his English was elementary, and that his reading skills were poor.

| Elders Wigginton and Chirwa with a family in Pointe Noire |

As it turned out, Elder Chirwa’s father was pursuing a Ph.D. in literature and had been named the Best Actor in Zambia in 1999. Chiloba himself had spent much of his childhood in England, and had an English accent. His sister, a doctor, still lived in England, as did his mother. Chiloba himself was planning on pursuing a degree in architecture. And he loved good books, especially those by Tolkien.

Chiloba “Chills” Chirwa would become dear to me, the African son I never met. He would also become a treasured friend to Elder Price. Both of them began their missions at the same time, and in fact communicated with each other before entering their separate Missionary Training Centers—Price’s in Utah, and Chirwa’s in Ghana.

Chiloba Chirwa wrote this to Elder Price on September 3, 2008:

Hello there Elder Price —

| Elder Price and Elder Chirwa |

I’m Elder Chirwa . . . I will be going into the Ghana MTC on the 19 of September and will be heading to the DR Congo mission. I have been surfing the net just trying to find out more about the mission!! You are the only one I have found that I will be serving with!!! Good luck with your preparations . . . see you in the field!!!

Elder Chiloba Anthony Chirwa

Brandon Price replied:

Hey Elder Chirwa! You have no idea how much it made my day when I read your email! I too have been surfing the net trying to figure out some stuff on the mission. I’m very excited, and a little nervous. Good luck in your preparations! I’m sure we’ll see each other at least once in the next two years!

In fact, they would see a lot of each other and sometimes proselytize together.

All of the missionaries in the DR-Kinshasa mission—and I—would learn precious and heart-wrenching lessons about love, sickness, death, faith, and compassion because of Chiloba Chirwa.

The Real Elder Price

The Real Elder Price, Part 3: Companionship

Missionaries move past differences to become a band of brothers.

By Margaret Blair Young, December 15, 2011

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author’s Introduction.

The song “You and Me, but Mostly Me” from The Book of Mormon Musical, could have been written for a Mormon film or road show. Every returned missionary could tell a story about hard companionships. The “mostly me” attitude is often the issue. What’s remarkable is how young men or women from different areas, and sometimes from different countries, learn not only to get along but to become brothers or sisters.

The learning curve is often grueling, and requires maturity beyond what we would expect of 20-year-olds. The differences between the musical’s Elder Price (a bright-eyed, most-likely-to-succeed type) and Elder Cunningham (a fantasy/sci-fi nerd) are quite common, as exemplified by one missionary’s description of his companionship in the DR-Kinshasa mission:

My companion: Sports sports sports sports sports!

Me: Okay.

Me: Star Trek, Star Wars, Doctor Who, various Babylon!

My companion: Yeah, whatever.

| Elder Chirwa singing with Elder Alex Healey |

In The Book of Mormon Musical, all of the missionaries are white. In most African missions, however, Anglo missionaries work with Africans, and many will have at least one African companion. Some cultural conflicts are inevitable.

Elder Henry Lisowski, from Canada, found himself in a difficult companionship with an African missionary from a country where aggressiveness was the norm, and argument seemed braided into tradition. As the companionship continued, their quarrels went deeper and lasted longer. Elder Lisowski’s initial instinct to repair the friendship devolved quickly into a determination to “show him he’s wrong!” Finally, the two were yelling at each other while tracting. This is Elder Lisowski’s description:

My companion started saying how all us white missionaries were failures, did things wrong, didn’t baptize, and how the African missionaries were real missionaries. He just kept attacking and attacking, and I just kept defending until I was so angry that I wanted to attack back. And this thought started in my head: “African missionaries are bad because . . . etc., etc.”

| Elder Lisowski and Elder Hunter, one helping the other |

As I considered what I was about to say, my mind froze. I realized, with instant clarity, that something had gone HORRIBLY WRONG. I was starting to think like a racist. It terrified me. I went silent. We got to the next rendezvous, and I told my companion to teach it because I COULDNT. My mind couldn’t focus. I was absorbed in thinking of everything that I did which led to this, and what I could do to FIX it. The rest of the day was a struggle . . . and constant prayer filled it. Halfway through our last lesson, all that poor, weak effort I had put forth for patience and love paid off. My prayers were answered, and everything just clicked. And all my frustration was gone, and I loved him again. We talked a little after, and resolved it, and things are okay now.

Such self-awareness and humility are rare in one so young—and were rare in Henry Lisowski’s pre-mission life. The mandate to serve in the name of Christ leads us to hard epiphanies.

Another African/Anglo companionship, between Elder Daniel Kesler (Utah) and Elder Aime Mbuyi (Congo), shows how service and honest conversation can fill the gap of a cultural divide.

Elder Mbuyi reported on how he and Elder Kesler learned to bridge their differences:

| Elder Henry Lisowski with Africans (dancing at a well dedication |

There were surely challenges. First, Elder Kesler and I tried to understand the differences in our culture. We talked openly about these differences and about how we cannot let them distract us or bring conflicts.

We learned to serve each other. For example, one day, my companion made my bed when I was working out. I started doing it too for him, and then we were doing it for each other. We were always looking for something to do to serve each other.

In the center of all this is the will to live the gospel. When we truly live the gospel we continually strive to become like Jesus Christ. My companion had this desire and I had it. And we became friends.

They all became a “band of brothers,” these missionaries. Elder Seth Lee once referred to them with that very descriptor. I told him I’d send him a candy bar if he could identify which Shakespearean play it was from. He gave me the correct response (Henry V), and immediately confessed that Elder Price had given him the answer. I sent them both Snickers bars, which arrived three weeks later. Shakespeare’s words do describe these missionaries, coming from all over the world and managing to bind themselves together: “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers!” (Act IV.iii)

| Elders Daniel Kesler and Aime Mbuyi |

Chiloba Chirwa’s entry into the band was heralded by Elder Wigginton: “We received a new Elder from Zambia! He just arrived today seems very sweet and funny. He also is a hugger! Awesome!”

Over the course of their missions, those two, Chirwa and Wigginton, would be paired twice, and would have their friendship cemented in some of the hardest hours either would endure.

On January 25, 2009, I received a strange email from Elder Chirwa, whose writing was usually well-phrased. This email was disjointed and full of misspellings.

dear sister young

thnkyou for your help. I am feeling terribly ill. I think i may have chicken pox. I hate bein ill its such a shady experience especially on a mission.

I cant wait to gt to the temple again. I may not remeber all the deatails but the warm feeling of being there is still with me.

| Missionaries praying before a soccer game |

We have had a busy week. we are wiorking on a teaching plan to focus on famillies and build a foundation for the district.

Thatnks again i am having a hard time concenrating on the screen, i mus t go .

Take care

As it turned out, Elder Chirwa not only had chicken pox but malaria.

Elder Wigginton reported a few days later:

Elder Chirwa is on quarantine for his chicken pox and malaria, and we spent four lovely days and nights at the medical clinic. Our arrival there was interesting. Last Saturday morning, resting trying to recover from my sickness, Elder Chirwa stumbled to his bed. I asked how he was feeling. He said bad, so I asked him to take his temperature again. It was 40 C, or 104F. I called the doctor and we got him checked in. His fever rose to 104.5 before we got there, and I supported him up the six flights of stairs. He was immediately hospitalized and stuck with an IV to bring down the fever.

| Elder Chirwa with Pointe Noire family |

We spent ninety six hours together with him suffering a lot. I felt for him when they came in to inject him with a syrup looking substance in his leg . . . the needle being over two inches long. He squeezed my hand and curled in pain as they sent this medicine through his quad. It was a ten by ten room and I had a little cot to sleep on.

His recovery took several days, and the chicken pox left him with some scars. I sent him ointment for the scars and a book on suffering by Neal Maxwell: If Thou Endure It Well—a book he would come to value deeply as his mission continued.

Soon after, my family and I spent two months in England, participating in BYU’s Semester Abroad program. Elder Chirwa’s mother and sister lived near London. He had given me their phone numbers, referring to his mother as “Loveness.” I thought was term of endearment, like “Beloved,” and didn’t realize it was her name until I met her.

| Elders Chirwa and Wigginton |

I embraced Loveness and Fiona (Elder Chirwa’s sister) just before dinner on May 30, 2010. Loveness introduced herself as “Chiloba’s mother,” and asked me if her smile was like his. It was.

That evening, the students had prepared a musical fireside, which we all attended. Several sang solos, and others talked about their favorite hymns. One told a poignant story. She had had a mini-stroke, which had partially paralyzed her. Her family was out of town, so she was alone in this terrifying condition, thinking she might die and finding herself unable to speak or move. She was rushed to a hospital, and kept singing the words to “Abide with me, ’tis Eventide” in her mind. Though she couldn’t form the words with her mouth, she kept singing them in her head.

| Margaret Young with Loveness Chirwa and Fiona |

Abide with me, ’tis eventide!

The day is past and gone;

The shadows of the evening fall;

The night is coming on!

Within my heart a welcome Guest,

Within my home abide.

O Savior, stay this night with me;

Behold, ’tis eventide!

O Savior, stay this night with me;

Behold, ’tis eventide!

The doctors and nurses were scanning her brain throughout the first hours after her stroke and could actually see the scans change when she was singing these words in her mind. They believed that her singing preserved her memory, which normally would have been affected. She testified that music lingers with us. It helps us remember.

After the fireside, Loveness told me her favorite hymn was “Come, Come Ye Saints.” That was the hymn that lingered in her mind. She was not as active in the Church as she had once been, but that particular hymn beckoned her, and she recalled all the verses.

| Elder Chirwa |

In 1995, she had been living in London and had met the missionaries. She wanted to be baptized but was afraid of how her friends and family would react. Finally, she just did it—without telling anyone. When her sister visited later, she also met with the missionaries and was baptized, as was Loveness’s husband, Jacob Chirwa. “So you see,” Loveness said, “I am the root. I began it all. Chiloba would not be where he is if I had not made that decision.”

She was so proud of her son, who was inviting others to believe the message of “Come, Come Ye Saints,” that in the eternal perspective, regardless of what trials interrupt our journeys or scar our feet, “all is well.” When I shared emails from Chiloba’s companions expressing their love for him, Loveness said, “That is good. That is very good.”

One of the students asked who my guests were. I answered, “I am very lucky. I have a bunch of sons serving missions in Cameroon. One of my sons is also this woman’s son.”

We could not have known that the entire Chirwa family was on the threshold of a tragedy, nor how it would impact all of us, and call on our compassion from across the continents.

Elder Chirwa’s father was about to die.

The Real Elder Price

The Real Elder Price, Part 4: Nightmares and Dreams

As so often happens, we find ourselves at the intersections of each other’s lives at just the right moment, tooled in ways we had not heretofore understood. We become angels for one another.

By Margaret Blair Young, December 19, 2011

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author’s Introduction.

On June 12, 2010, I emailed Elder Chiloba Chirwa, telling him that I had just received a gift from his mother—a copper plate with the name ZAMBIA on it. Two days later, I got an email from Fiona, Elder Chirwa’s sister: “Jacob has been ill and has passed away today. It is completely devastating, but we are staying strong and know that we will be reunited as a family again.”

Elder Chirwa had lost his father. I emailed him immediately, starting with the subject line “I already know.”

Now the missionary companions—this “band of brothers”—was called upon to mourn with their friend.

Elder Lisowski described the scene in the missionary apartment:

I found out the same day he did, before he ended up coming home. I tried to make the apartment as comfortable as possible and just figure out how I could help. He came in kind of shell shocked, and eventually told us what had happened. I’ve just spent the past couple of days sitting in his room whenever he’s there. I’m not surprised that you know, either. I actually talked with Chirwa a little bit about it. “What do you think Sister Young is thinking right now?” His response was along the lines of “There’s no way she knows.” So I gave him a look which in essence said, “Sister Young . . .not knowing something?”

| Jacob Chirwa in a casual moment |

I was amazed at the ways I had been woven into Elder Chirwa’s life, without ever having met him. Regardless of the physical distance between us, we were bound in a relationship that called upon us to care for one another. He was my brother, my son, my friend.

“It’s hard for me to hold back tears right now,” he wrote to me. “We should be grateful for the lives that have touched ours. I am grateful for my father. I was blessed to be his son.”

As it happened, I had a gift for Elder Chirwa, though I had not anticipated it would come into use now, or that it would serve as a comfort to a grieving missionary. Months earlier, I had interviewed Jacob Chirwa via email, fascinated by his knowledge of African literature and curious about LDS art in Zambia. It took him awhile to answer my questions, because he was studying in Finland, the very place where my own father had served his mission. When he replied, he was thoughtful and direct:

I have as yet to see any form of artistic manifestation in the church around us. I have always felt that there hasn’t been enough encouragement for the local artist to showcase their talent. One reason for this is the belief inculcated in the people that the only approved art manifestations are the ones coming from Utah. And so we sit to watch videos of conversion stories as our missionaries do their work. This is well and good but I feel that watching a local missionary at work in any outside place would impact our youth.

The fact that Jacob’s own son was serving as a missionary in “an outside place” made his observation poignant and personal. Indeed, Elder Chirwa would make an inspiring subject for a Church video or a film. Having already suffered with malaria and chicken pox, he was now bearing the burden of his father’s death. He acknowledged the challenges with a very Mormon insight on the ways pain catalyzes our personal evolution: “There just seems to be no end to the obstacles on my mission. I can’t help but wonder what the Lord is molding me into.”

I sent Jacob’s interview to Chiloba.

He could have returned to Zambia for the funeral, but elected to remain where he was. He sent these words to be read at the memorial service:

| Elder Chirwa and Elder Lisowski with a family in Pointe Noire |

I am realizing quickly that the comfort of the Spirit is not only a voice telling you all will be all right, but it is a deep, even limitless understanding of eternal truths. The Spirit tells to trust in the knowledge of God, giving us understanding of His omniscience. It also helps us understand the time-defying state of forever—that perspective which we call Eternal. In this comforting scope of understanding, death is a mere temporal separation . . . I love you all. I am with you in spirit. I love my father and all he was and did. Let us remember him, let our hearts not be broken but filled with love and appreciation for Jacob Chirwa. Let us remember that God’s grace is sufficient for us. He will see us through.

Just over a year later, my own father appeared to be dying. He had already been on dialysis for three years, and was now bleeding internally. When the doctors stopped the bleeding, Dad had heart attacks. When they prevented the attacks, his bleeding worsened. It appeared that we were in a Catch-22 which would end his life.

I continued to communicate with Elder Chirwa, who was now in the final stretch of his mission. Though he was half my age, I knew he understood what I was going through in a way the others in the “band of brothers” couldn’t.

“You were there for me,” he wrote, “and I will be there for you.”

I poured my heart out to this young man I had never met, this remarkable missionary whom I had so grossly underestimated when first introduced to his name. How I loved him! I wrote: “This process of losing my father—and I don’t know how long it will take—is so much harder than I ever imagined it would be. I wish we didn’t have this one thing in common, but it helps to know that you know.”

| The Youngs with Robert Blair |

In reply, he sent me the lyrics to a country song:

And when you dream, dream big

As big as the ocean blue

‘Cause when you dream it might come true

When you dream, dream big

“Sister Young, dream big,” he added. “The plan of our Heavenly Father is greater than we can understand. Today I received a birthday card that Dad had gotten me but never got to sign. My aunt found it in his diary. I was happy. My aunt said that Dad would have loved to give me the keys to the world. Despite him not being there to do so, I have a Heavenly Father that surely will.”

There would be yet another surprise amongst Jacob Chirwa’s papers: a poem he had written prophesying his own death, as though he had dreamed it.

| Professor Jacob Chirwa in a professional moment |

The funeral cortege is long,

longer than any that I have ever seen…

All I know is that before I was placed here

There was a large crowd of people wailing

As they passed by me.

I must confess

I have never seen such ugly and contorted faces in my life,

Faces all screwed up

As if they had been forced to swallow an overdose

Of quinine tablets without water,

All howling at the top of their voices,

Calling my name…

There were a lot of people

peeping into the coffin where my body lay in state.

I even saw what would have been

A beautiful girl

if her face was not contorted.

She peeped and I think she smiled, and was gone…

And so it continued,

This long line of people walking past and mumbling.

At one point, I almost burst out laughing

when one of them said,

What a handsome face!

I thought to myself,

What, me—handsome?Actually, I am ugly.

The ugliness that makes the owner aware of it.

Everything on my face is a sort of

culmination of God’s craziest adventures in creativity . . .

So you now understand my amazement

when this person mentioned

My being handsome.

| Elder Chirwa and others playing |

Had Jacob Chirwa considered himself ugly? Was he genuinely surprised that someone would think him handsome? Certainly, he was admired in Zambia. His wife reported that he was renowned not only as an actor but as an expert on Isaiah. His sister-in-law said that just days before his death, he had taught a beautiful Sunday school lesson, using his acting abilities to their fullest, completely comfortable with his class. And yet there were his own words—the suggestion that he did not recognize that he was handsome.

Jacob’s poem reminded me of some plot points in the musical Man of La Mancha, based on Cervantes’ Don Quixote. An old man, who appears delusional, imagines that he is actually a knight and must do good and worthy things to earn a noble title. Ultimately, he fights a giant (really a windmill) and demands that a barber give him a title. The barber puts his shaving basin on Don Quixote’s head and dubs him “Knight of the Woeful Countenance.” Thus ennobled, Don Quixote seeks a virtuous woman to whom he will dedicate all of his battle victories. He selects a prostitute/scullery maid as the object of his affection—imagining her out of her rags and into resplendency. Ultimately, she is changed by the way he sees and treats her. Her eyes are opened to her own glory. Later, when Don Quixote is forgetting his own quest, she begs him to remember what he had stood for: the impossible dream. Just as he had awakened her to a sense of something greater than she had dared imagine, so she awakens him to a remembrance of his own nobility. Even if his dreams have been “impossible,” his heart has been good, and he has lifted the downtrodden by treating them with dignity.

There is an “impossible dream” in The Book of Mormon Musical, too, though not an inspiring one. In fact, it’s quite the opposite of the Quixotic illusion. “Spooky Mormon Hell dream” shows the missionaries encumbered by their own and others’ absurd expectations, laden with shame, supposing they have been revealed as “unworthy” and then tormented by medieval devils, who come complete with horns and pitchforks. (Devils in real Mormonism are much more subtle and sly.)

Of course, as good satirists, Parker and Stone have identified the Mormon proclivity toward guilt as a fruitful subject for humor. In “Spooky Mormon Hell Dream,” the missionaries are haunted by memories of petty misdeeds from their childhoods, and dream that Jesus hates them and denounces them with a vulgar epithet. Tyrannical fathers rise from the sludge of memory to ground them for stealing donuts—or breaking one of several hundred missionary rules.

| Robert Blair being supported by his son and grandson |

“Spooky Mormon Hell Dream” is the perfect counterpoint to “I Believe.” In the latter, there is no hierarchy of central and subordinate/irrelevant/false doctrine. In the Hell dream, there is no hierarchy of misdeeds. Stealing a donut and them blaming it on your brother is tantamount to committing genocide in Nazi Germany.

In Mormonism as we actually live it, things are far more complex and full of promise. We do burden ourselves with guilt, but we are not unique in that. More important is the fact that we undertake impossible dreams—such as making missionaries of teenagers and sending them to places like Africa. In the best of times, and when we are living our religion, our dreams are magnificent and overflowing with love and compassion—including toward ourselves. And often (more often than we recognize), those dreams come true.

Chiloba Chirwa, a knight of radiant countenance, dreamed big, and had sweet memories of the father he would never see again in mortality. “Before my mission, I overheard a telephone conversation between my dad and mum,” he said. “She asked him if he felt I should go on my mission, and he replied ‘I think he has done well enough to go.’ I always knew that he supported what I was doing.”

I had a dream once that I was about to meet Chiloba Chirwa. He was just turning to look at me, but then disappeared as I awoke. But though I have never met him, I have heard from those who know him well that no photograph does him justice. He (no doubt like his father) is far more handsome than a camera can reveal.

| Elder Chirwa kicking his heels |

Miraculously, my father survived the crisis and lived to celebrate his 80th birthday with his family. All of my siblings had flown in for this, uncertain if we would be eating a birthday cake or planning a funeral. At 2:00 p.m. on his birthday, supported by a son and a grandson, Dad walked into his own home.

I was not yet called upon to endure the loss of my father, as Chiloba had done. But the realization that I had “been there” for him—that I had been alerted to his loss so that my words were waiting when he was able to access a computer; that I had interviewed Jacob before he died and thus could give Chiloba his father’s own words; that I had met Chiloba’s mother and sister—appeared miraculous. As so often happens, we find ourselves at the intersections of each other’s lives at just the right moment, tooled in ways we had not heretofore understood. We become angels for one another. That’s the real Mormon dream.

The Real Elder Price

The Real Elder Price, Part 5: The Face of the Other

We are asked to gaze as far, as deep, and as magnanimously as possible. The only justified assumption is that we never know another’s heart.

By Margaret Blair Young, December 22, 2011

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author’s Introduction.

According to The Book of Mormon Musical, the Ugandan attitude toward God is “Hasa Diga Eebowai”—a fully gesticulated, profane curse against Heaven for the hardships of African life: starvation, AIDS, droughts, etc.

South Park humor style. But hardship in Africa is no joking matter. Missionaries there meet the realities of governmental corruption, poverty, disease, domestic abuse, alcoholism, and more. No missionary serves his full time without coming face to face with tragedy.

The Ugandans in The Book of Mormon Musical are as Americans might imagine them. The invented Ugandan curse is something Americans might predict—however inaccurately. Where there is so much death and devastation, we might presume that families would not bond tightly to their children; that in places where early death is common, parents would grieve only superficially, recover quickly, and then have more babies. “Hasa Diga Eebowai” makes that sort of supposition (“Try living here a couple days—watch all your friends and family die!”), and depicts the Ugandans shrugging over their harsh realities, and simply throwing their hands up. Though I find most of the songs in the musical fun and often accurate, “Hasa Diga Eebowai” is not one I will listen to again. I believe it perpetuates dangerous assumptions.

Why dangerous? Assuming that we can assess another’s selfhood and predict reactions can shrink our compassion and reduce the other to a mere extension of our own experience, something we can contain within our finite expectations. These flattened supposals can get a laugh in a Broadway satire, but in real life, the telescopic imagination is called for. We are asked to gaze as far, as deep, and as magnanimously as possible. The only justified assumption is that we never know another’s heart.

| Elder Price with a child |

Of course, the Mormons in the play are also flattened to suit the structures of satire, but we recognize a few of their characteristics. The mission president, for example, appears as the proverbial, patronizing white guy, oblivious to how condescending his words are. He compliments the missionaries on the work they are doing with the “noble Africans”—echoing the reference to Native Americans as “noble savages” during the 19th century, before they were corralled and exiled to the Trail of Tears. He pronounces the elders “one with Africa,” and they eagerly believe them. Still utterly naïve, they sing “I Am Africa,” using images from Disney’s Lion King, and proclamations like “We are the Lost Boys of the Sudan” and “We are the tears of Nelson Mandela.”

The real Elder Price and the Mormon boys called to Uganda or the DR-Kinshasa missions did indeed weep with the Africans, and tethered their hearts to them in ways that will affect them for the rest of their lives. There was no self-congratulation involved.

Elder Henry Lisowski wrote evocatively about the death of a 5-year-old boy from malaria:

In the corner of the room was his body. Lying shirtless and lifeless on the couch, he seemed so calm compared to the chaos that reined around him. Placed on his stomach was a warm iron, prostrate, like a plea to God himself. “Don’t take him from me, not yet. Let me have just a little more time with him.” The iron was to slow decomposition, something that normally hits rapidly in Africa. In this way the family could at least finish their mourning before burying him.

In the center of the room were the women, the source of the tumult. Wailing, screaming, and crying, they pounded their hands mercilessly against the concrete ground, sometimes calming down enough to look back up at the child, which would drive them into an even greater frenzy. In the corner sat the boy’s uncle, our age, curled into a ball and gasping for air as tears rolled down his face. And silently sitting on the front steps was the grandfather, weeping into his hands.

And so we stood with the others, guarding the family during their time of need. There were about 40 of us crammed into that alleyway, heads hung, listening to their cries.

| Elder Lisowski playing |

Elder Jared Wigginton wrote about the poverty of Samuel, a refugee:

Samuel’s father, an African, was a General for the Arab-controlled government of Sudan. Having African roots in a village just east of Darfur made his father’s life difficult, as his own people viewed him as a traitor. In July of 1993, his father’s gas station was burned and destroyed, and his father was kidnapped and murdered. With no source of stable income and a fear for their lives as tension was growing, he and his family fled to the Central African Republic.

After four years in Kinshasa, he met the missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and decided to be baptized. Six months later, he received a phone call telling him his mother had died in Pointe-Noire, Congo. He decided to find her burial site and try to establish a new life.

On his third day here, having eaten nothing, he saw the steeple of our church. He attended the Sunday service. I was able to talk with him for a while and I took him to talk with the Branch President to see how we could help him.

My heart twinged a bit when he and President were talking in Lingala, and I watched him empty his pockets of a bar of soap in a plastic bag and a toothbrush with every bristle bent back and a deep yellow. He was showing the President everything he had to his name.

The yearning for some connection with the divine is one of our most common human experiences, and perhaps especially acute amidst poverty. A recent Mormon convert, Marceline Beri, told Elder Wigginton about her desire for peace during years of illness and abuse. He recorded her words:

| Baptism of Marceline Beri |

I knew God existed. Maybe because I was desperate, I started praying. Each time I prayed, I found myself sobbing—I don’t know why. I felt a big relief. I was so dirty. Spiritually, I was weak. I could not listen to the voice of God, or hope that I could progress and get myself out of my suffering.

As Beri’s words show, this longing for a connection to God can be overwhelming. Africans do not shrug, curse God, and die in the face of enormous adversities. They, as do all humans, ache for meaning. And the Anglo missionaries, though their stay is brief, though they do not “become Africa” (their passports prevent that, providing a guarantee that they can leave whenever they choose), do take something of Africa back to their homes. The memories of the people abide with them.

These memories do include some rather scary people carrying AK-47s.

One of the funniest moments in The Book of Mormon Musical happens when Elder Price tries to push faith beyond his fear. He has just seen a warlord murder someone. In a parody of Maria singing “A captain with seven children—what’s so scary about that?” in The Sound of Music, Elder Price sings, “A war lord who shoots people in the face—what’s so scary about that?”

It may seem that Parker and Stone have gone beyond the pale with this kind of “man up” initiation for the missionary. In fact, culture shock can be violent, and I know of missionaries who witnessed murders on their first day in the field. And there are certainly warlords, revolutionaries, and refugees throughout Africa. Some even become Mormon converts. At least one revolutionary in the Congo became a missionary: Aime Mbuyi.

| Elder Aime Mbuyi |

I have been communicating with Elder Mbuyi for a year now. He is still serving his mission and is currently the Assistant to the President. English is his second language (French being his first), so I have adjusted some grammar and word choice, but will let him tell his story in his own words:

Before I joined the Church, I was in a revolutionary group. We had a camp which was like a boarding school. One of the purposes of this camp was to teach us to abandon the religious system brought by white men, and to return to the religion of our ancestors. At the camp, we lit a bonfire, sang songs, and we prayed to our ancestors. Someone called out to the ancestors and other dead ones and asked them to mingle with us. All of this was initiated by an African Catholic priest who was the leader of the camp. He also changed the way of celebrating Mass. It was no longer a Catholic Mass but a combination of Catholicism and African ancestor worship. We also watched documentaries about Patrice Emery Lumumba, the youth of Soweto and others. This ex-priest was building hate in us.

I had many destructive plans which I developed at the revolutionary camp, but I did not put them into action. The gospel changed my heart before I executed my plans.

My grandparents joined the Church in July 2005 before I came back to live in Kinshasa after spending seven years in Tshikapa, where the revolutionary camp was located. My grandpa told me about the Church just once. He said that it was a good church. It gave the youth opportunities for a good education and helped them become good citizens of the country. He said many things about the Church, but I did not show that I was interested. My mother tried to encourage me to visit the church. The next Sunday, I did. I did not inform anybody at home. I knew where the church was.

I entered. I passed the chapel and found myself in the bishop’s office. I told him that I was new in the church and that I did not know where to go. He showed me a class. Afterwards, I encountered the elders and we made an appointment. I do not remember what was taught that day at church, but I remember my impressions. I was impressed by the attitude of the young men my own age who blessed the sacrament. They were like angels.

Most of my friends thought that the Church was not Christian. At first, I did not tell them I had joined it. I was ashamed. My mother encouraged to stop going to the camp meetings. She said, “Aimé, now that you have received the gospel of Jesus-Christ, I think you must stop your meetings and your organization. You have become a disciple of Christ.” Her words touched my heart, and I decided to stop. I found an excuse to escape my friends. This decision helped me be focused in the gospel and ponder in my heart the message I had accepted.

| Sister Pamela Headlee with Elder Mbuyi’s Mother |

The knowledge of the plan of salvation gave my life a new orientation. But it was when I received the testimony from the Spirit that Joseph Smith was a true prophet of God and consequently that this work was true that I understood that I was actually struggling against God by my revolutionary group. I had a strong conviction that anyone who aims to bring division into the world instead of peace is not from God.

Many thoughts were coming into my mind. It was not easy to give up the struggle. I thought about the purposes of the revolutionary group, but even more about what I was fighting for. Thoughts were continuing to come into my mind telling me that God was the master of everything, that He knew everything, and that He could permit everything to happen for good purposes.

I felt a strong desire to share what I knew with people. I remember when I testified of Joseph Smith to my classmates. I still remember those feelings I had. After a few weeks in the Church, I was already nicknamed “the Mormon” or ” man of justice”(“homme de la justice”) at school.

In the same period, I learned the children’s song starting with these words: “We have been born as Nephi of old.” This song fostered my desire to serve the Lord and has been until now a constant source of comfort and courage to serve Him with all my heart and power.

| Members and missionaries singing in Pointe Noire, Republic of Congo |

In 2007 I was called to be the ward mission leader and started working with the full-time missionaries. This period prepared me and confirmed my decision to serve a full-time mission. I received my mission call from the Prophet on November 30th and started my mission in December 29th, 2009. I went to the Mission Training Center in Ghana.

Long before I went into the Ghana temple as a missionary, I knew that it was the House of God. Two years earlier, my cousin had come to me and told me that he had had a discussion with some people who had just been in the USA. He said that these people had told him bad things about the Church and its temples. He told me many things against the Church and especially the temple. I was troubled. My spirit and mind were troubled. I was afraid. I remembered what the missionaries told me: “You can ask God to know if what we have taught is true.” I then prayed in my heart, meditated and prayed to know the truth. After a short while as I was in meditation, a feeling of peace, assurance and joy replaced the feelings of fear, doubt, confusion, and trouble in my heart. I was happy. I knew that I was headed in the right direction, and that the temples of the church are the very Houses of God. Later I testified of these things to my cousin, who finally decided to also join the Church.

When I entered in the Ghana Temple for the first time, I submitted many names of my ancestors, and ordinances have now been done for them.

I love the gospel.

Elder Mbuyi continues to serve as a different kind of revolutionary—a soldier for peace in the army of the Lord.

Through tragedy and joy, love and loss, the missionaries approach those around them (including their companions) with growing tenderness and respect. Such is the case for both the Anglo and the African missionaries. Elder Mbuyi, who will remain in the Congo when his mission ends, speaks warmly of those who walked with him as fellow citizens in the household of faith, who have now returned to their comfortable homes in North America: I love [my former companions] very much. I miss them. I am sad that I may not see them again before many years or forever.

There are no acquiescent shrugs in the final missionary days, and the song most likely to be sung will certainly not curse God or pretend that there isn’t an ocean between Africa and North America. It will simply plead, “God be with you till we meet again.”

The Real Elder Price, Part 6: The Dedication

We Mormons dedicate ourselves, our homes, temples, churches, and land — whether the land is for someone’s burial or for the preaching of the gospel.

By Margaret Blair Young, December 26, 2011

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author’s Introduction.

Comedy, particularly satire, tends to simplify and exaggerate characters and content. So it’s no surprise that LDS Church leaders, as depicted in The Book of Mormon Musical, are either goofy or tyrannical—and capable of teeter-tottering to either extreme. In the satire, the mission president is an implacable hard-liner. When it’s clear that the African converts haven’t received the orthodox gospel from the missionaries, but something profanely different, the president explodes. He pronounces the missionaries all failures, and then declares that he’s sending them ignominiously home. The same guy who had gushed that these teenaged ministers had “become Africa” is now in a rage, and fulfilling every fear provoked by the “spooky Mormon Hell dream.” All he lacks is a pitchfork and a tail.

In real, unexaggerated life, I know a lot of currently serving and former mission presidents. The one I know best is my father. I remember well when he got a phone call inviting him and my mother to Salt Lake City for something. For a week, we Blair kids were left to speculate about what our father was being asked to do. Finally, we had a family meeting, and Dad reported what had happened.

He and Mom had been invited to talk to Elder Dallin Oaks, sustained by Mormons as an apostle. As it happens, Elder Oaks is also a family friend, someone we have joked with, eaten cake with at wedding receptions, and greeted at funerals. But in this setting, he was acting in that apostolic assignment. He told Dad that the Church was ready to open a mission in the Baltic States, which had been behind the Iron Curtain since the 1940s, and asked if Dad, with Mom at his side, would preside over it. They both agreed, not mentioning the other things in their lives that would make such service difficult. (Two of my siblings would marry during my parents’ time in the Baltics. Mom returned for one of the weddings, but we Blair kids represented our parents at the other.) There would be no financial compensation for this service; the three years were consecrated time.

| President and Sister Blair in the Baltics |

For my husband, Bruce, and me, the experience of witnessing my parents being set apart for this assignment was awe-inspiring. When Elder Oaks entered the room, it was with a power that distinguished him from Dallin Oaks, the attorney and friend with whom we laughed in everyday associations. This was no social gathering, but as serious and as sacred as when Christ sat in Peter’s boat and asked him to “thrust out a little from the land” (Lk. 5:2).

My uncle John Groberg, functioning as Elder Groberg, placed his hands on his sister’s head, and pronounced a blessing of comfort. Mom was desperately insecure about leaving her home and family. He told her she could do this thing, and that she had been prepared in ways she didn’t realize.

Elder Oaks laid his hands on my father’s head and set him apart. Until he spoke the blessing, I had not been aware that Dad was worried about his unfinished tasks and projects. When Elder Oaks instructed him to not concern himself with what he was leaving behind, my father openly wept. The blessing also included a promise that my parents’ children would be watched over, that others would be brought into their lives to help and support them.

And so Mom and Dad went to Eastern Europe, where my family and I visited them a year later. One of their missionaries said to me, “Your father is the most inspired man I have ever met.”

Since I knew my father much better than this young man, that pronouncement was two degrees shy of mind-boggling. “My father?”

“The most inspired man I’ve ever met!”

That generous imagination and the Mormon sense that anyone who answers the call to discipleship may be duly empowered had added a divine dimension to the man I called simply Dad.

In my own little family, we have also experienced this magnification. My husband and I were released from our calling at the Missionary Training Center when he was asked to be our congregation’s bishop.

I remember the voicemail that let me know a change was before us: “Brother Young, the stake president would like to meet with you. Sister Young, we’d like you to come as well.” I knew immediately what was before us, and knew that our time in the MTC was about to end.

In his office, our stake president pulled a letter from his desk. It authorized him to extend this call to my husband. I did not want to leave the missionaries, and Bruce had no idea of how difficult this stewardship would be.

We said yes.

Such is the line of authority we Mormons accept. There are some things only a stake president or a bishop or an apostle is authorized to do. This hierarchal order has troubled some, who think we worship men rather than God, and put them on absurd pedestals if they have high callings. (Well yes, we do have rather high pedestals, which is a natural outgrowth of the LDS claim to continuing revelation and the amazing possibility that there are still prophets on earth.)

| Elder Holland with branch president Bala and others in Yaounde, Cameroon |

According to this line of authority, only an apostle will dedicate a land for the preaching of the gospel. It was Elder Jeffrey R. Holland who dedicated Cameroon (part of the DR-Congo mission) when “my” missionaries were there.

His dedication of Cameroon was the fulfillment of a 133-year-old prediction, articulated in the Deseret News on December 7, 1877:

Stanley the traveler has furnished the world with a complete map of the course of that mighty river, the Congo, down in Africa. A fresh field is opened to missionary labor. The benighted tribes of the wilds of Africa will not long be left without the knowledge of the world’s Redeemer. This is the great and last dispensation in which all that is hidden shall be disclosed, and all nations and lands with their history and relationship to each other will be made manifest. The emancipation of the colored race in the United States and opening up of the long hidden regions of interior Africa are indications of the workings of the Almighty towards the lifting up and final redemption of this branch of the human family. The fullness of the gospel may not reach them for years. But the angel which restored it to earth proclaimed the glad tidings that it should be preached ‘to every nation and kindred and tongue and people.’

Of course, the article is imbued with the prejudice of its time and the concepts that undergirded colonialism, but the Mormon view of ever-increasing light and progress is unmistakably present, as is the understanding that all mankind comprise the “human family.”

It also responds to the fictional Elder Price’s singing “I believe that in 1978, God changed his mind about black people.” No, the principle that “all are alike unto God” is eternal. God has never changed His mind about that, regardless of what any mortal has said.

And so Elder Holland dedicated the land of Cameroon for the preaching of the gospel. I’ll let the missionaries describe the events in their own words:

Elder Henry Lisowski: It turned out we would NOT be able to go to the dedication after all. So, we eight missionaries sat silently at 7:30 in the morning, looking out toward the mountains, and waiting as our country was dedicated. There was no parting of clouds, no brilliant rays of sunshine frying the wicked, and no falling fireballs. But it was still pretty cool.

| Elder Jeffrey Holland on Dedication Hill |

Elder Jared Wigginton: We heard of the power of the Spirit that was present [at the dedication]. Elder Holland’s prayer compared the missionary work to the rock upon which it was given in the hill—a rock of Christ with the potential to roll and grow beyond measure. He put to shame with Apostolic authority that Africans were ‘fence sitters’ in the pre-existence and admitted that the reason for the Priesthood restriction is still not known today. He edified us. I understand so much more clearly why I am serving.

Elder Chiloba Chirwa: We shook the hand of Elder Holland. I will never forget the experience of today. He pronounced a blessing upon all the people of this country, and I know that everything he said in his dedicatory prayer will be fulfilled. I am still trying to compose myself. What a privilege it was to gaze into those piercing blue eyes and listen to his apostolic voice.

Elder Kendell Coburn: We had the wonderful opportunity to have a zone conference with Elder Holland. The most powerful thing he did was to bear testimony of the Savior. His apostolic testimony was one of the most powerful moments of my life. My joy is full. I am overflowing with happiness and peace. And I am so grateful to be a missionary here in Africa.

Elder Seth Lee: We got the opportunity to meet Elder Holland personally and be taught by him. His message to us focused on three important things: focusing on the scriptures to teach the doctrines; enjoying our time on our missions; and his personal testimony of the truthfulness of the Church and the divinity of what we are doing in Cameroon. I love that man, and now I’ve got a new favorite quote from an Apostle. He said, “A boy becomes a man when he has served in Cameroon!

| Missionaries on Dedication Hill |

Elder Daniel Kesler: Elder Holland didn’t have to recite some preplanned talk, but he was able to just share exactly what he needed to. It was huge when he looked at us and said, “Nothing on earth can change my testimony. You can make me happy or disappointed, but nothing you can do will subtract from my testimony.”

Elder John Ternieden (who translated for Elder Holland): I was very nervous and had my face in Liahonas for about two weeks practicing translation. I wish I could have thanked him because it was a real testimony building experience for me. I felt the Spirit SO strongly with his message, and that same Spirit translated the words. I just happened to be the mouthpiece.

Elder Brandon Price: Elder Holland talked about how our church doesn’t have a ‘symbol’ like many others. He said that if he could choose a symbol, it would be two missionaries. Then he said, “You are worthy symbols.”

| Companions, Elders Price and Lisowski on Dedication Hill |

The missionaries asked if they could take a picture with Elder Holland. He agreed, but said there would be one condition: Complete silence. Elder Price explains:

He told us that he wanted us to remember an apostolic testimony, not a photo. His last counsel was that as quickly as the spirit comes, it can go away. Then, he got in the car and was off to the airport. It was all finished just as quickly as it began. But, the blessings of his short visit were great. Nearly 400 members and investigators got to hear and be taught by an apostle, the country was dedicated for missionary work and blessed, and a small group of sixteen missionaries had an incredible experience.

| Elder Holland with the missionaries (zone conference) |

This attention to reverence has drawn my thoughts often as I’ve considered the principle of dedication. We Mormons dedicate ourselves, our homes, temples, churches, and land—whether the land is for someone’s burial or for the preaching of the gospel. A spirit of reverence accompanies the dedication, but it can be easily disrupted by the chaos of everyday living, the incessant lure of music with a good beat, of a situation comedy, or of a Broadway musical. The thought makes me wonder if I can fully appreciate the kind of stillness that leaves space for the calming breath of God to be heard and felt, and to linger. It makes me want to take long walks and simply meditate, or to be on a hill overlooking a promised land and hear the timeless strain of hymns—past, present, and future.

| Author (Margaret Young) with Elder Marion Duff Hanks |

As it happens, I also knew and loved the man who presided over the British Isles mission when Elder Jeffrey Holland served there in his youth: Elder Marion D. Hanks. My family and I visited Elder Hanks periodically until his death on August 5, 2011. Any mention of Elder Holland always brought these words from him: “I love Jeff.”

My parents, nearly a decade after their service in the Baltic States, still get visits from their missionaries. The missionaries, said Dad, were “my friends, my sons.” He trusted them, and found them worthy of that trust. Sometimes, the “line of authority” is simply the cord of the affection lacing one heart to another.

| Mission President Michael Headlee and Pamela Headlee, and senior couple Brent and Lynda Willis |

On the first evening I met them at the Missionary Training Center, I told the missionaries that the French language would become sacred to them, because it would be the language they spoke at holy times. I told them that the countries in which they would serve would also become sacred because of what they would experience. In Mormonism, we believe that a grove of trees was sanctified by a young man’s answered prayer; that a normal piece of land did actually contain buried scriptures. In a more personalized perspective, any place where our yearnings have found comfort and direction is sanctified. At the ends of our lives, we could map out our own “sacred groves”—those places in our minds or in our rooms where we met something divine and heard an answer to prayer, even if we didn’t realize we were praying.

Note: This essay is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Elder Marion Duff Hanks.

The Real Elder Price, Part 7: To Boldly Go

Such are the journeys and sacrifices Mormons make to get to sacred ground. Sometimes these journeys are physical, and sometimes they are spiritual.

By Margaret Blair Young, December 29, 2011

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author’s Introduction.

At one point in The Book of Mormon Musical, my eyes teared up. It was when Elder Price, singing “I Believe!”, leaped into the Ugandan village and declared “Satan has a hold on you!” It wasn’t his declaration that moved me, but his leaping into the unknown. It reminded me of Elder Henry Lisowski, who reported his growing bravery in these words:

One other change I’ve noticed is how much I like and am able to just talk with people about the Gospel. Before, I was shy, wouldn’t talk to anyone, was AFRAID to, and just didn’t bother anyone because I was afraid they’d get upset at me. After a year and a half of praying, it would seem that all of that fear finally just . . . disappeared. And now, things like this happen:

Walking through the quartier, I see an open door.

Me: “Target locked!”

Elder Wagman: “What?!”

Me: “Target locked, we’re going in! Stay on target!”

Elder Wagman: “What!?”

(*walk through the door*)

Elder Wagman: “We can’t contact them, they’re eating togeth. . .”

Me: “HELLO! We’re the missionaries and we’re going to sit down right here and talk to you about the gospel. Where are some chairs?”

(I may not have said it EXACTLY like that, but that’s what HAPPENED. . . .Wait, the whole target lock stuff I did actually say).

Basically, realizing that this week has made me happy.

| Missionaries holding church sign |