This is the roster for The Race Horse, a ship which sailed from South Africa to the USA. On it were Susan Talbot, one of my ancestors on my Blair line, her many family members, and a Xhosa slave, Gobo Fango. (Xhosa refers to a particular area/dialect in South Africa.)

I knew the history of Gobo Fango before I realized that I had a family connection. In fact, I wrote an article about him for BlackPast .

Gobo Fango’s history has been written from a few perspectives, some depicting him crawling to his deathbed and willing all of his money to the building of the Salt Lake Temple. I already knew the narratives which pioneer descendants tended to believe about slaves in their family. It’s a three-point narrative:

1) When my ancestors joined the LDS Church, they freed their slaves.

2) My family offered freedom to their slaves, but they wanted to remain slaves. (You should see the eye rolls when black audience members hear this.)

3) My family treated their slaves like one of their own children.

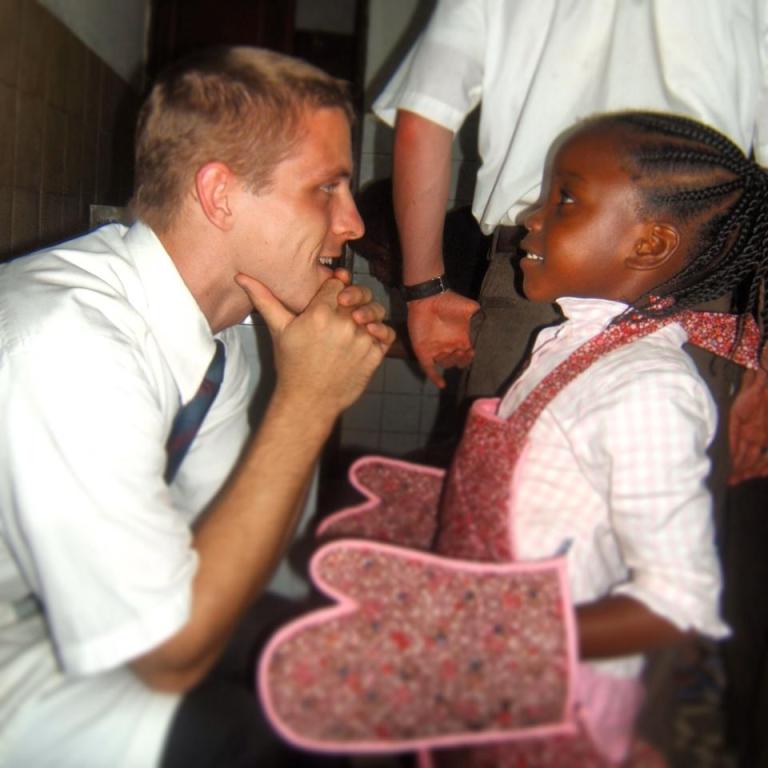

An article in The Friend, March 2003, shows this narrative. Here’s a quote: “Gobo was a valiant Saint… a courageous child from South Africa. He was one of the first African pioneers to join the early Saints in the West, and he is a member of our family.”

Actually, there is no record indicating that Gobo Fango was ever baptized. Was he a “member of our family”?

What we know is that he slept in a shed and suffered frostbite on his feet as a result. He had a noticeable limp for the rest of his life. We know that the Talbot family sold him to another family (Whitesides) who subsequently sold him to another family. Note that the families arrived in Utah in 1861, the year the Civil War started. Slavery was abolished in 1863 by the Emancipation Proclamation, so sales of Gobo Fango after that year were illegal. There were two sales.

Gobo was shot and killed by Frank Bedke over property issues in 1886. Gobo himself was unarmed. The first hearing of the case against Bedke ended in a mistrial. The second trial found that he had killed Gobo Fango as in an act of self-defense.

The article in The Friend describes one of the Talbots protecting Gobo Fango from discovery on the ship:

“Quickly Sister Talbot lifted her large hoop skirt and hid him underneath. Gobo pulled his knees tightly against his chest and held his breath until the mob left and his mother took him upon her lap. She reminded him that he was a child of God and explained that their home with the Saints in Utah would be a place of acceptance and love for their entire family, including Gobo. She assured him that their fellow brothers and sisters in the gospel understood what it was like to be persecuted and judged. Surely they would not turn Gobo away.”

We desperately want to believe that our pioneer ancestors treated everyone as children of God. We want to believe that our people provided “acceptance and love” to all. In this particular case, I already knew the tragedy of Gobo Fango’s life before I realized that my own family was involved.

Gobo Fango was a lone black man in Oakley, Idaho, separated from the white families. He slept in a shed, resulting in frostbite, and he became a sheep herder. He was killed by a man who was subsequently acquitted of the murder. Anything beyond those facts is speculation.

My experience in researching stories of black pioneers has revealed the ways we adjust the narratives to exonerate our own families. The narratives are transmitted down the generations, and some research (along with an open mind) is needed to challenge them.

The need for acknowledgment of our historical wrongs–even those of our ancestors–is essential to healing. As Desmond Tutu said of Truth and Reconciliation:

“How could anyone really think that true reconciliation could avoid a proper confrontation? After a husband and wife or two friends have quarreled, if they merely seek to gloss over their differences or metaphorically paper over the cracks, they must not be surprised when they are soon at it again, perhaps more violently than before, because they have tried to heal their ailment lightly.”