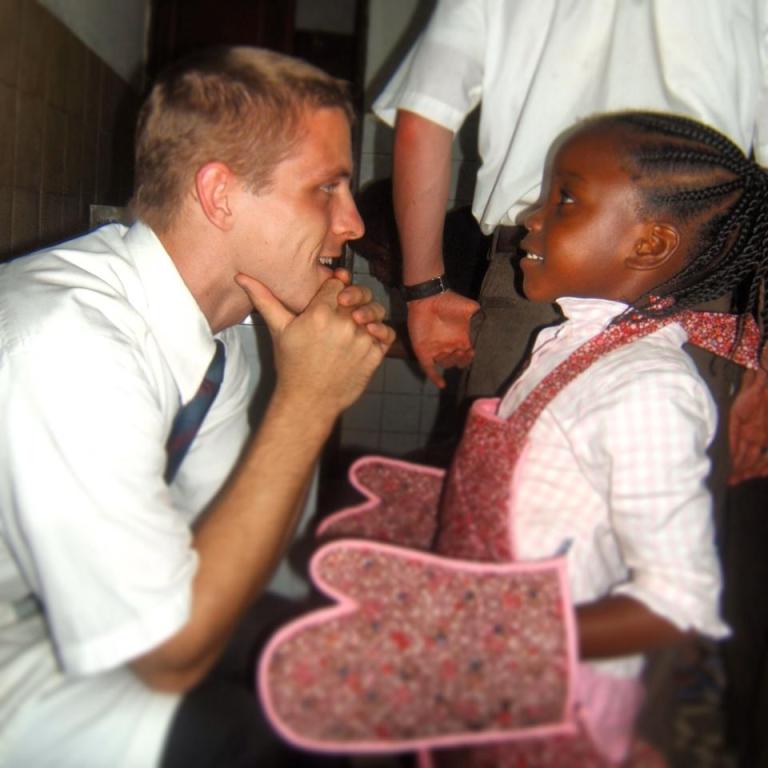

A couple of weeks ago, while I was in Lodja, Democratic Republic of Congo, I was invited to a huge family gathering in honor of a powerful man who had gone from Lodja to important positions in the country’s capital. There were at least one hundred people gathered to celebrate him and to greet me. They danced, shouted, trilled, and otherwise rejoiced. At one point, a little girl came forward with her plastic doll. The girl was a short-cropped beauty, dark and adorable. Her doll, however–a good-sized one typical of what an American girl might find under a Christmas tree–had blonde hair and blue eyes. She timidly pushed it towards me. This doll was a cultural connection, an “I have something that looks like you!” bridge. I smiled in recognition. Yes, that was an American doll, and the doll bore some resemblance to one of my grandchildren.

A couple of weeks ago, while I was in Lodja, Democratic Republic of Congo, I was invited to a huge family gathering in honor of a powerful man who had gone from Lodja to important positions in the country’s capital. There were at least one hundred people gathered to celebrate him and to greet me. They danced, shouted, trilled, and otherwise rejoiced. At one point, a little girl came forward with her plastic doll. The girl was a short-cropped beauty, dark and adorable. Her doll, however–a good-sized one typical of what an American girl might find under a Christmas tree–had blonde hair and blue eyes. She timidly pushed it towards me. This doll was a cultural connection, an “I have something that looks like you!” bridge. I smiled in recognition. Yes, that was an American doll, and the doll bore some resemblance to one of my grandchildren.

My role at that moment was to just be present, to enjoy the people. My presence in Africa, however, always suggests power simply because of the cultural dynamics. Though my American home is modest by American standards, my access to pretty much anything I want is unimaginable to those gathered around me in Lodja to celebrate one of their own. I would not even attempt to describe the Thanksgiving feast which awaited me after my long flight from the Congo to Utah, USA.

Likewise, Americans (myself included) do not “get” Africa. The image of the starving African is certainly drawn from reality, but the whole truth of what it means to be African–to have an ancestry which experienced kings, queens, chiefs, tribal wars, glory, slavery, and greatness, and now celebrates family with unfettered joy and swaying hips–that Africa is beyond comprehension. Any American who presumes to understand it is simply being arrogant. This is a lesson I learned from my linguist father as he became fluent in dialects in many countries, and which I continue to learn as I discuss philosophy with my husband. The “other” (meaning the other person, even a person as close as a brother or sister) is infinitely unknowable. This is even more true when there are cultural divides. Nonetheless, that unknowable “other” also calls us to responsibility. Within it, that mysterious face carries the command, as Levinas said, “Thou shalt not kill.” But the command goes deeper than that and into the New Testament directive:

Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world. (James 1:27)

Every face we encounter as we live out our mortal lives calls us to help. We will not be able to help more than a few of those we meet, but we are hard-wired for compassion, and in our most natural state, we will yearn to help at least those few. Approaching that responsibility must mean the complete surrender of presumption or prejudice.

When I speak about literacy in the DR-Congo, some Americans suggest that Kindles would work great. Unlimited libraries on devices no larger than a notebook. It sounds easy and wonderful! Of course, these good-hearted souls don’t have a real sense of the starting point for our projects. You can’t have a Kindle unless you have the ability to charge it. And having books on hand won’t help anyone who can’t read.

In the “bush,” where many of the children I met live, there is no electricity. The sun governs the day. And in many parts, there are no schools. Even in places where schools exist, education is not free. It costs $12. USD a month for a family to educate their child–and the school is not always within walkable distance. Some choose not to do it, or simply cannot afford it.

My efforts during my August trip to the DR-Congo were all about assessment. What do they have? What do they need? Where do we start?

My efforts during my August trip to the DR-Congo were all about assessment. What do they have? What do they need? Where do we start?

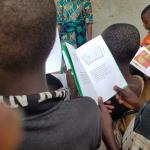

On my second day there during that August trip, I discovered the site African Storybooks. I was thrilled! The characters were African, and I could print the booklets in French. The children would be reading stories about people who looked like them and who knew the kind of life they lived! I had a printer with me, and printed about one hundred booklets, which were distributed to four schools in Kinshasa. As preparation for my November trip to do follow-up and to attend a film festival (we are also working with Bimpa Productions in Kinshasa to get cinema up and running in the country), I printed out 250 booklets and took them as flat-pages at the bottom of my largest suitcase.

In Lodja, I began putting the books together, reinforcing them with folded construction paper. I worked with a Congolese scholar, On Okundji Ekanga Blaise Veron, who is also a Catholic priest. “Abbe Veron” gave up a lucrative professorship in France to return to his war-torn village and build hope. His main concern when I met him during the August trip was that the young people were in a moral vacuum with no plans for a good future–or even a sense that one was possible.

In Lodja, I began putting the books together, reinforcing them with folded construction paper. I worked with a Congolese scholar, On Okundji Ekanga Blaise Veron, who is also a Catholic priest. “Abbe Veron” gave up a lucrative professorship in France to return to his war-torn village and build hope. His main concern when I met him during the August trip was that the young people were in a moral vacuum with no plans for a good future–or even a sense that one was possible.

As one who teaches creative writing and tells students that they will never write well if they don’t read widely, I recognize the importance of books–and particularly fiction books, which push the imagination to inspire students to dream, to envision a future, to dare to explore possibilities beyond the obvious. I knew that these books could be the beginning of new dreams in the Congo, and of a future not yet imagined, but which will be. These books could be a huge part of restoring hope to a place disrupted by the chaos of war.

I looked especially for titles which told success stories. In the future, I plan on volunteering for African Storybooks in supplementing their archive with stories from the Congo, and with translations into some of the dialects there. The resource is vital.

The books use full color pictures, which mattered to me. My printing cost for 250 books was about $400. That money came from my husband’s and my personal funds, and was some of the best-spent money of our lives.

The look on the children’s faces when they perused these books which would now comprise their storybook library? Well, see for yourself.

If you are interested in getting involved, contact me directly.