(This series about antidepressants is posted during Mental Health Awareness month.)

For some, the attempt to discontinue antidepressants is a life-or-death dance. Something in the brain of a person who is discontinuing sends alarming signals. Often these impulses leave one with the singular feeling of rage that focuses on the need to self-destruct or to destroy something or someone else.

For those who are discontinuing, if during one of these rage-filled moments, they are lucky enough to cling to the knowledge that this impulse is chemical and manage not to kill themselves or somebody else, then the battle has taken ground, but only by an inch. Even if they do manage not to act upon these impulses, there will be many more battles to come.

The key to understanding why these symptoms show themselves as they do lies in the chemical manipulations caused in the brain when a person is taking an SSRI.

The term itself — ‘Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors’ — is a roundabout way of saying these drugs inhibit the natural recycling of serotonin. In simpler terms, it is helpful to think of SSRIs as running defense on the natural cyclical flow of serotonin between nerve endings.

In a normal nervous system serotonin in the brain is sent from the “sending” nerve ending to a “receiving” nerve ending. The locus of this exchange is the synapse — the no-man’s land that exists between sending and receiving nerves. The “Sender” releases serotonin which enters the synapse, there to be absorbed into the nerve ending of the “Receiver.” Whatever serotonin is not absorbed by the Receiver gets flushed back into the Sender to be recycled and eventually re-released, making for a lively give-and-take between the Sender and the Receiver. When SSRIs are introduced they change the terms of this dance. The Senders still send and the Receivers still receive. But those random bits of serotonin that don’t get initially absorbed are blocked from being recycled into the Senders and forced back into the Receiver, thus the denotation “serotonin re-uptake inhibitor.”

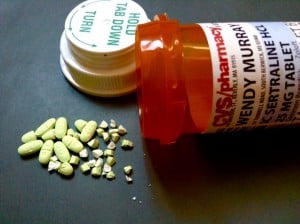

The logic of this blockage is this: Studies that arose during the 1950s, when brain chemistry science was in its formative stage, happened upon the notion that the lack of serotonin in the brain directly affects depression, psychotic behavior, and anxiety. Thus, the optimal way to treat depression, according to this theory, is to increase serotonin levels in the brain. Hence, the development and rise of SSRIs and their subsequent exponential dissemination. (By 2008, antidepressants were the third-most-common prescription drug taken in America.) The theory about the role of serotonin in the depressed person’s brain has been challenged and studies have come out contradicting it.

But this new information is of little help to the millions whose brains have been altered by SSRIs and who remain bound to them, in many cases, against their wills.

As noted, SSRIs increase serotonin in the brain by forcing molecules back into the Receiving nerve ending that otherwise should have been reabsorbed by the Sending nerve ending. As a result, the brain is experiencing more serotonin impulses on the Receiving nerve, which enables the patient to feel better for a while. But this effect is temporary.

When the drug is preventing the serotonin from being recycled, it means two things:

- for a time, the Receiver is over-stimulated by forced serotonin, while,

- the Sender is gradually becoming depleted because of the lack of recycling.

Because the Senders become depleted and thus stop sending, further depleting the number of receptor sites, this results in the commonly-called “poop-out” syndrome, necessitating an increase in the dosage of the SSRI in order to maintain the positive plus-serotonin effect. “There are fewer receptor sites [so] you’re getting depleted, you’re running on empty on serotonin. All those drugs ‘poop out’ and stop working after a month or so. So then you have to raise the dose,” says physician Dr. Gary Kohls.

In essence, the serotonin-sending function actually becomes depleted because of the very medication intended to increase it. Because of the inevitable depletion of the Senders and Receivers, these drugs stop working effectively after a time. “SSRIs increase serotonin only on the synapse level, and that is temporary, altering the brain at least long term and maybe permanently in some cases,” says Kohls, adding, “with a lot of damage being done in the meantime.”

The re-uptake-inhibiting process that SSRIs use to increase serotonin levels in the brain is at the heart of why SSRIs are so difficult to quit. By blocking serotonin receptors on Sending neurons, the natural send-receive synergy has been interrupted, and as a result the brain becomes chemically dependent upon the drug to maintain consistent levels of serotonin. As the brain becomes accustomed to the drug, it no longer resorts to its normal function of producing or regulating serotonin and no longer functions with the normal cycle of sending, receiving and recycling of serotonin.

During the process of tapering, as the SSRI chemical is removed from the now-altered brain, the levels of serotonin fluctuate in the neurotransmitters. The systems gets gummed up and the brain isn’t firing on all pistons, the way an engine in a car would get gummed if some sabotaging agent were thrown into its pistons. This fluctuation causes wide mood swings and uncontrollable emotions, as evidenced in the struggles of the thousands of people on forum websites.

The brain is trying to adjust to the need to self-regulate levels of serotonin. In the meantime, many patients experience a cascade of extreme emotional and physical symptoms that include debilitating depression, anxiety, panic, rage, confusion, agitation, crying spells, insomnia, memory loss, general aches, headaches and heart palpitations. These symptoms can feel quite unmanageable and so intense that you become hopeless in the face of them and see no way out. The electrical impulses in the brain are going haywire and the result is that the standard mechanism used to control emotions is no longer functioning appropriately.

Withdrawal triggers the mind to respond more viscerally and in a way completely disconnected from normal thought processes and standard restraints. Uncontrollable rage springs fully formed in the mind and propels itself toward an unsuspecting target, as if an external force has hijacked that person’s personality, as indeed it has. The compulsion is trying to take over my consciousness.” Other emotional symptoms of withdrawal act in a similar way — inexplicable crying fits, overwhelming panic. Even for the patient who exercises mindfulness and self- awareness, these symptoms come on with little warning causing great turbulence and possessing a visceral realness that most people find alarming. The brain’s chemical balance has been disrupted, so reality itself for the patient has been altered. Instead of an emotional wave that must be conquered or endured, these emotions become reality itself, with a feeling of inevitability that sometimes ends in tragedy.

To be continued . . .