Last week, in the first of three articles I outlined what I believe to be a way to move beyond the zero-sum games that shape public discourse. Relying on game theory, I pointed out that while there are viable ways of talking about an infinite game that does not presuppose a belief in God, for Christians the best way forward is to nurture what we might call “God’s infinite game.”

That game is theocentric and is predicated on the conviction that we are all made in the image of God. It also assumes that when we lapse into zero-sum games, we “distort and attenuate what we can learn about God and – because we are made in the image of God – about one another and ourselves.” I concluded by noting that in “an age of rage,” it will not be easy for Christians to advocate for God’s infinite game. “Fundamentalists of both the left and right will ignore or reject those efforts. They will argue that it betrays the orthodoxies of their respective camps, and both will argue that a theocentric agenda fails to take ‘the current crisis’ seriously. But God’s infinite game has always drawn that kind of criticism and this should not surprise or discourage us.”

In this article, I turn my attention to the question of where this infinite game is played. On that score, there is considerable confusion, particularly among Christians.

The advent of the “social gospel” in the early Twentieth Century; the emphasis on prophetic preaching in the 1960s; studies devoted to the “politics of Jesus” in the 1970s and 80s; and the contemporary emphasis on social justice left the impression that historically the church had been quietist and fixed exclusively on personal piety. More significantly, all four movements also created the impression that the place where God’s infinite game is played focuses on shaping public policy.

As a result, an increasing number of Mainline-become-Progressive Protestants and others have concluded that the primary place in which Christians are called to respond to God’s calling is in the public arena, alongside others who are fighting the zero-sum game of American politics. No small number of contemporary writers have been at pains to identify Jesus’ teaching as essentially political, and some go so far as to argue that the teaching of Jesus is, in essence, if not in name, one with modern political points of view. (Thus, for example, the anachronistic claim that Jesus was a socialist.)

It is not surprising, then, that the same zero-sum political game has also invaded the church. Modeled largely on the political structures of colonial America, Protestant churches in the United States often have their own versions of a constitution and legal statutes. Many have some sort of bicameral legislature, decisions are often made on the basis of parliamentary procedures, and national conventions are the place where decisions are made. Worship and prayer are featured, but in truth, there is no connection between these activities and the decision-making process and, over time, the same machinations that are so common in the civic domain have exposed the process for what it is: A pale, under-funded version of American party politics.

This complex mix of theological and historical assumptions overlooks two very simple facts (among others): One, Jesus addressed his vision of the Reign of God to his Jewish contemporaries and showed no interest in Roman politics of his day. Two, the subsequent followers of Jesus clearly understood locus of his message to be the church.

It follows, then, that the infinite game that God invites us to play is to be played out in the body-life of the church. It is there that God’s game is recognized. It is there that those who play are recognized as having been made in the image of God. It is into that game that others are invited to play. It is also there that the healing of God’s image is achieved, if the church is faithful in the game that it has been invited to play.

That what Christians believe about the will of God should shape the decisions that they make as citizens, there can be no doubt. That the witness of the church to the infinite game that God invites people to play will have an influence on society, cannot be doubted. And there is certainly no doubt that if the church plays the infinite game well, the witness of its life will have an impact on the larger society.

But if Christians assume that the locus of that game lies on the national stage, it does what it is doing now:

- It adopts the zero-sum game that is played on the national stage.

- It sublimates the language of the game that God has invited the church to play, exchanging a conversation about the image of God for the language of rights.

- It focuses on the changes that can be made now in the name of winning, rather than the changes that are entrusted to God as the church risks itself in the effort to be faithful.

- It compromises the church’s witness to God’s infinite game, revealing that it is just as much in thrall to zero-sum gaming as any other part of society.

- And, of course, it compromises the very game into which God has invited us, by infantilizing the life of the church – a subject to which I will turn my attention in the third and final article.

[This article is the first in a trilogy and what will follow is a biblical and theological rationale for playing God’s Infinite Game]

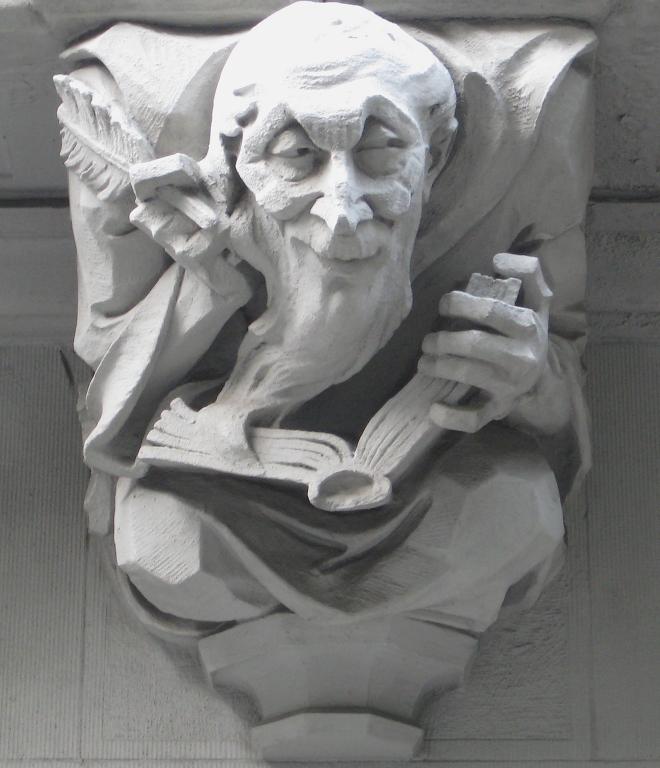

Photo by André Noboa on Unsplash