“A teenager was riding in a crowded compartment with five strangers. His mother had given him a sandwich wrapped in a handkerchief for his lunch because rationing made food for travelers hard to come by. Noon came and he was hungry, but he didn’t want to eat his lunch in front of the other passengers. He decided to wait until they got out their lunches, but no one moved. An hour passed and then another. Finally, his stomach rumbling, he decided that he had no choice. He needed to eat, and so did the others sharing his compartment. He reached in his coat pocket and took out the handkerchief. He spread it on his lap and carefully broke his sandwich into six pieces while the other passengers watched in silence. Then he said a brief blessing and gave each passenger a part of his sandwich. Then everyone else reached into their pockets and bags and took out the food that they had brought—and not wanted to eat in front of others who might not have anything. The food was broken and shared around the compartment with a sense of feasting. Stories and laughter were shared along with the food.”

That’s a really charming story, and it’s the kind we have probably all heard in sermons on Matthew’s feeding of the multitude, because it is one of the most common explanations offered for the miracle that Jesus performs. It has been since the 19th Century. The crowds follow Jesus into a deserted area. It is too late to get home or go to the market, and in the act of sharing, the generosity of Jesus prompts everyone else to share.

But the problem with this explanation is that there is absolutely nothing in the story to suggest that is what Jesus or Matthew had in mind. What both the contemporaries of Jesus and the Jewish readers of Matthew’s Gospel would have heard were allusions to Deuteronomy 18:15-18:

“The Lord your God will raise up for you a prophet like me from among you, from your brothers—it is to him you shall listen— just as you desired of the Lord your God at Horeb on the day of the assembly, when you said, ‘Let me not hear again the voice of the Lord my God or see this great fire any more, lest I die.’ And the Lord said to me, ‘They are right in what they have spoken. I will raise up for them a prophet like you from among their brothers. And I will put my words in his mouth, and he shall speak to them all that I command him.

The passage in Deuteronomy promises that with the death of Moses, God will continue to send Israel prophets. But by Jesus’s day, that passage had also become a common part of Messianic expectations: God had promised a new Moses. And here he is, Matthew is saying, in a deserted place, gathering and feeding Israel with manna. He cares for them as Moses cared for the children of Israel. And – as if Jesus had not already made his point – there is enough in the way of leftovers for twelve tribes.

We could talk about the case for the existence of God and the evidence for miracles in connection with this passage. But in a way, that subject is as much off-point as the story we began with. The story assumes that Jesus offered a sign here in feeding the people. What is more on-point is this question: What kind of Kingdom does Jesus point to in this miracle? A Kingdom made possible by God or by right-thinking people?

I say that because I suspect that preachers who have told stories of transforming generosity when they reflect on this story are not just repelled by the miraculous. They are equally repelled by the notion that our well-being, in fact, our very futures are dependent upon God. It is easier, somehow more respectable and even more attractive to believe that Jesus is all about human and social transformation, than to believe that our transformation and the transformation of our world might be dependent in the final analysis, upon God and on our willingness to surrender our lives to God.

You see that a lot right now, even in the church. Christians are just as enthralled to politics as any other American, and just as much at odds with one another over which kind of politics is the right one. Even the solutions to the challenges that we face revolve around the same theories that are part and parcel of our civic discussion. If, our problem from time to time has been that we have over-spiritualized the challenges that we face, now the problem seems to be that we see no spiritual dimension to the challenges we face at all.

I am sure that such conversations have a contribution to make. All truth is God’s truth. But I am also equally certain that if the Gospel slips from the center of our preaching, or if it is subtly transformed into a message of either personal or social improvement, we will no longer be preaching the same message that we find in the Gospels.

So, again, what kind of Kingdom does Jesus point to in this miracle?

If one takes the Gospel story on its own terms and avoids explaining it away in one fashion or another, the answer of course, is pretty clear.

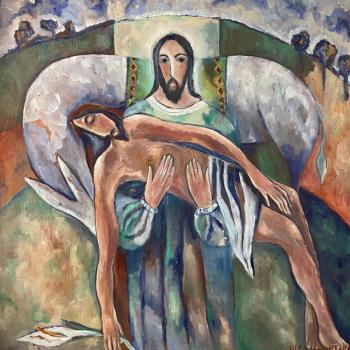

For one thing, the feeding of the 5000 is an epiphany. It is a manifestation of the divine and reveals important truths about Jesus and the Kingdom of God. It is also a public enactment that points the crowd to a specific conclusion: Jesus is the new Moses.

He is the one who cares for his people in the wilderness, who offers an understanding of the Law that transcends their efforts to pin its requirements down to a few obligations. But he is more: The miracles he works announce the presence of the Kingdom, and they also reveal his identity. In a short, the Kingdom of God is the Kingdom enacted by God.

It is not a place or a territory, unless one thinks in terms of the reclamation of all creation as a place. And it is not a policy or a program. In English, in fact, it is more accurate to talk in terms of “the Reign of God.” Because it exists only when and where people live in dependence upon God, only when and where they are fed and cared for by God, only when and where people hear God’s word and do God’s will.

Similarly, the one who feeds them is more than the expected prophet of Deuteronomy. He knows the will of God with an immediacy that the best of his contemporaries lack. His teaching cannot be reduced to a program and the miracles that he works, reveal his divinity.

Settling for anything less, when we talk about Jesus – be it Jesus, the spirit-filled man; Jesus, the charismatic; Jesus, the cynic philosopher or great moral teacher; or Jesus, the proto-socialist fall well short of what the Christian faith claims. Distorts what we make of him and of the Reign of God. And none of these views of Jesus are the basis of the church’s faith and its creeds.

As important as it is to know that Jesus is Immanuel – God with us, in it, all the way – that identification with our circumstances is little consolation, if Jesus is no more than a profoundly empathetic human being who is willing to expose himself to danger. There are countless figures past and present of that kind. None of them command our attention and devotion in the same way that Jesus does.

Where does that leave us, as the disciples of Jesus? Exactly where both the crowds that followed Jesus and the disciples who gave him everything that they had to feed the people: A life of availability. That availability is not availability to a particular program, to a political party, or to an alternative creed but to the purposes of God.

What does that look like? Let me offer an example.

The very presence and intensity of the conversations, not to mention the deaths and statistics that so many have discussed, demonstrate that racism remains a problem in our country. At the extremes of that debate are people who deny that there is a problem or would prefer to ignore it. And at the other end of the spectrum are those that have discussed the issue in a way that threatens to introduce a new variety of racism into the national debate.

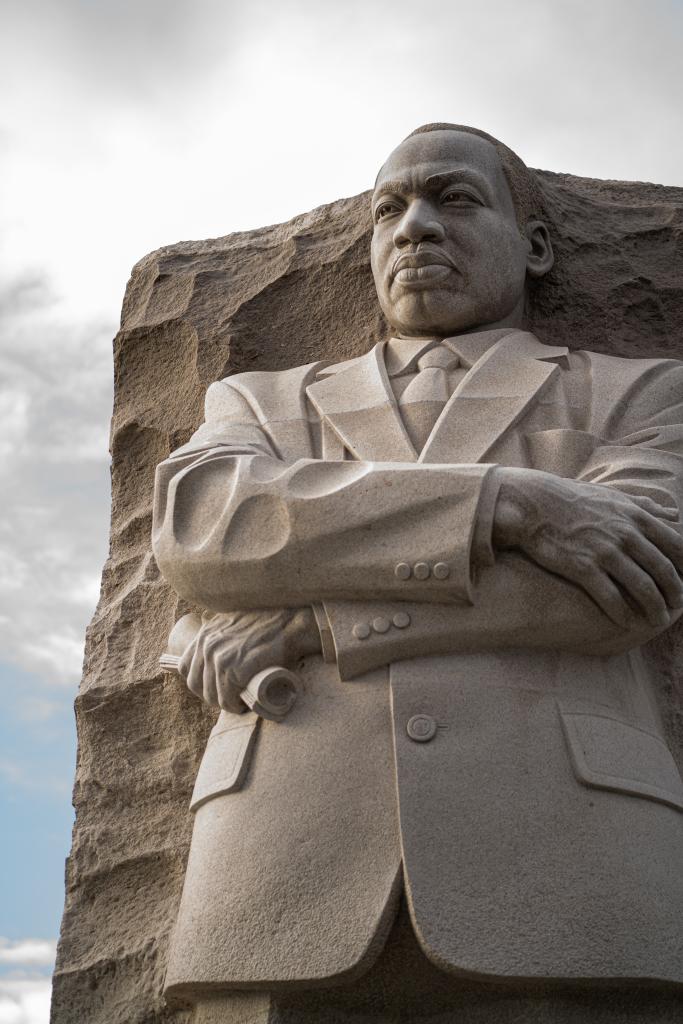

By contrast, Martin Luther King and Congressman John Lewis, who died this week lived lives of availability to the purposes of God. They believed in forthright witness and protest in the face of racial injustice, but they resisted violence. They longed for healing that addressed those issues but celebrated a God-given dream that transcended the divisions of their day, but they were concrete and specific in the efforts that they made.

I am convinced that kind of availability can still give us a place to stand – on racism and any of the other difficult questions that we face as Christians. It will not be a comfortable place, because it will not provide a place to hide and because it will not allow us to “take sides” or sign up for one kind of partisanship or another in any part of our lives. It will not allow us to flatly praise some and demonize others. Instead, it will be a place where our first and decisive question will be, “How can I be available to the purposes of God’s reign?” If we ask that question, like Jesus, we will often find ourselves at odds with the world around us, but it will lead us back into the world at peace with God.

Photo by Rob Curran on Unsplash