For a long time, sin and guilt were really unpopular subjects in American life.

For a long time, sin and guilt were really unpopular subjects in American life.

Until recently, if they figured in the American psyche at all, it was the toxic projection of antiquated religious ideas, and its best antidote was good therapy. Only on a rare occasion did it feature in public conversations. The experience of Tiger Woods comes to mind. People weighed in on his personal trials, declared him guilty and recommended that he seek absolution in a public confession-come-conversation with Oprah Winfrey.

Sin and guilt were so unpopular, in fact, that one book asked, Whatever Became of Sin?[1] And more than once over the years, I have had seminarians tell me that I am the only

professor who has ever mentioned it. That’s extraordinary, when you think about it, since sin and the burden of guilt have been at the heart of the Christian faith for centuries. Whether one thinks of the church’s hymnody, its creeds, or its message, both have played an important part in describing “the human condition.” For that reason, they have also played an important part in describing the saving work of Christ.

But sin and guilt are back, and they are back, as the center piece of the new American religion: Politics. It is so central to that religion that it has acquired its own literature; its own liturgy; its own means of finding confessing one’s guilt; and its own priesthood. Chief among its practitioners is Robin DiAngelo.[2] (Who knew that there could be so much money in religion beyond the fundamentalist world? It’s enough to make Joel Osteen blush.) But it has become so generalized throughout American culture that it has replaced the old deistic religion of America at the beginning of every baseball and football game.

- But, as one might expect from a religion with such shallow roots, this new American religion also has features that are at odds with any deeply considered theology of sin and guilt.

- It lacks a relevant god, because there is no agreed set of civic convictions that there is one – let alone what that god would be.

- Its definition of guilt is racial, not universal.

- That sin is ontological, not moral. (i.e., It is predicated on who you are, not on what you’ve )

- There is no confession to be made, certainly not private confession.

- There are no confessors, apart from ill-defined groups that may hear your confession. And, for that reason, there is no guarantee that your confession will be held inviolate, because – by definition – there is nothing confidential about a public confession.

- It offers no absolution, because you cannot be absolved of something that is imprinted on your body.

- This new religion has little or no interest in the amendment of life that follows on confession, because amendment of life robs both sin and guilt of its political potency.

Tragically, this distorted use of sin and guilt has moved to the forefront at a difficult juncture in our national conversation about race. But the distorted version of the conversation about guilt will have predictable results: It will become an obvious tool of political manipulation. It will resonate with some, inviting a public and largely self-referential exercise in virtue-signaling. It will repel others and breed cynicism about the value of that conversation.

Frankly, I have little hope of shifting the public conversation about sin and guilt and that is not my purpose here. Those changes will only happen if enough people of enough races join hands to make common cause against the divisive and corrosive nature of this new religion. In the absence of a different kind of religious orientation, the conversation about sin and guilt will always lurch between therapeutic, legal and political categories – if it receives any treatment at all.

What I can do and plan to do here is offer an orientation to sin, guilt and its resolution as understood in the Christian tradition and then I would like to return to the issues I have outlined above. In that way I can speak to issues that are within my wheelhouse and do the one thing that I can do as a priest, theologian and spiritual director: Offer a way that Christians might orient themselves to the context in which we find ourselves. This forum doesn’t offer a space to do that at length, so I have tried to be as direct as possible:

Guilt, properly understood arises out of the choice to sin and as such alerts us to the dangers inherent in those choices.

In an article entitled, “When Guilt is Good,” Libby Copeland describes research on the subject of guilt that was conducted not long ago:

A few years ago, researchers in Germany set out to plumb the moral consciences of small children…

The kids’ reactions revealed a lot about how social-emotional development progresses during these key years. While many of the 2-year-olds seemed sympathetic to the researcher’s plight, the 3-year-olds went beyond sympathy. When they believed that they’d caused the accident, they were more likely than the 2-year-olds to express regret and try to fix the tower. In other words, the 3-year-olds’ behavior varied depending on whether they felt responsible.

Their actions, according to Amrisha Vaish, the University of Virginia psychology researcher who led the study, demonstrate “the beginnings of real guilt and real conscience.” Vaish is one of a number of scholars studying how, when, and why guilt emerges in children. Unlike so-called basic emotions such as sadness, fear, and anger, guilt emerges a little later, in conjunction with a child’s growing grasp of social and moral norms. Children aren’t born knowing how to say “I’m sorry”; rather, they learn over time that such statements appease parents and friends—and their own consciences. This is why researchers generally regard so-called moral guilt, in the right amount, to be a good thing: A child who claims responsibility for knocking over a tower and tries to rebuild it is engaging in behavior that’s not only reparative but also prosocial.[3]

The description is sociological, therapeutic, and reasonable. There is also no doubt that there is some truth to the observations that Vaish makes. But, as with most phenomenological descriptions of how we are shaped and formed, the description hardly explains why “guilt” as a thing exists at all, never mind why it might be “reparative” or “prosocial.”

The Bible offers a more basic explanation. Guilt is what we experience when we attempt to be our own god. Eugene Peterson’s rendering of Genesis 3 is a paraphrase, but it does a good job of revealing what is at stake in the story that Genesis tells:

The serpent was clever, more clever than any wild animal God had made. He spoke to the Woman: “Do I understand that God told you not to eat from any tree in the garden?”

The Woman said to the serpent, “Not at all. We can eat from the trees in the garden. It’s only about the tree in the middle of the garden that God said, ‘Don’t eat from it; don’t even touch it or you’ll die.’”

The serpent told the Woman, “You won’t die. God knows that the moment you eat from that tree, you’ll see what’s really going on. You’ll be just like God, knowing everything, ranging all the way from good to evil.”

When the Woman saw that the tree looked like good eating and realized what she would get out of it—she’d know everything!—she took and ate the fruit and then gave some to her husband, and he ate.

Immediately the two of them did “see what’s really going on”—saw themselves naked! They sewed fig leaves together as makeshift clothes for themselves.

When they heard the sound of God strolling in the garden in the evening breeze, the Man and his Wife hid in the trees of the garden, hid from God.

God called to the Man: “Where are you?”

He said, “I heard you in the garden and I was afraid because I was naked. And I hid.”

God said, “Who told you you were naked? Did you eat from that tree I told you not to eat from?”[4]

The link here is clear. Guilt is not a pleasant sensation and our instinctive response is to evade God and hide. But, as unpleasant as it is, guilt also alerts us to the distance that we have placed between ourselves and God by longing to be our own gods.

It isn’t necessary to believe that this sensation has been imposed upon us by an ancient set of relatives (per the doctrine of original sin). That isn’t the point of the original narrative in any event. What the teller of the Genesis narrative is trying to say is human beings regularly do these things. In a hundred and one ways we try to be our own gods and – when we do – we rob ourselves of the intimacy and companionship that God offers us. Then, in quick succession the blame game begins – our relationships with God, with one another and the world around us spiral out of control – and (as the encounter between Cain and Abel illustrates) someone gets killed.

What this story tells us, then, about sin and the guilt that accompanies it is very different from the American religion of the moment. Sin is ultimately a spiritual problem in that it disrupts our relationship with God, as well as other human beings. Sin and guilt are universal. They are not isolated to one part of the human race. They both flow from the choices that we make. And sin, in all its forms, is an equal opportunity employer.

All of this is at odds with the contemporary definition of racism. According to the current narrative, racism and the abuses that flow from it are uniquely the sin of whites. And the struggle sessions that DiAngelo orchestrates are what passes for confession in the world of her consultancy, turned religion. But, of course, this is, quite simply, from an historical point of view completely false. Like most forms of sin, racism is as old as the human race itself, and it continues to bedevil human behavior in a variety of ways, all around the world.

One of the stunning things about the narrative in the early chapters of Genesis is its effort to say something of a universal nature about the human race. Coming from a tribal culture in a tribal world, one might have expected something more partisan and particular. Of course, in one sense, Genesis does make very specific claims about God. But the writer(s) also follows the implications of that claim, subordinating ethnic claims to the transcendent nature of God. Genesis does not depict a people who are not more virtuous than their contemporaries. The forefathers and foremothers of Genesis are not immune to making the choices that all human beings make. They regularly make the same bad choices as everyone else.

To acknowledge this is not to deflect from cases in which some white people are motivated by racism. It is to insist, however, on a clear-eyed assessment of the variety of ways in which racism and other kinds of prejudice are manifested, the breadth of racism’s presence in humankind, and the variety of forms that it takes. It is also to resist definitions of racism that obscure other problems that we face: the disregard for people of color whose neighborhoods have been roiled for decades by violence and murder, the tolerance for failing schools in those same neighborhoods that urban leaders refuse to acknowledge, or the disproportionate number of African American children who are aborted, all serve to illustrate what I have in mind.

Dealing in a healthy and grounded fashion with sin, be it racism or any other form of sin, also involves recovering other Christian assumptions and practices that have shaped the church’s approach to sin and guilt for centuries.

Each of these deserves more space, but here they are in an abbreviated fashion:

At the outset, a distinction needs to be made between shame and guilt. Shame is ontological and attaches to the individual as a state of being. An awareness of sin is not meant to foster shame.

Guilt, on the other hand, arises out of choices and actions. And in helping people respond to their sins and the guilt that follows on those choices is not about making people feel inferior or badly about who they are. It is about the effort to free ourselves of those choices that we make, choices which destroy our relationship with God and with others.

Confession and absolution are the opportunities that the church provides for making that possible. Effective use of those spiritual practices requires confidence in the goodness of God. Confidence in a confessor that hears those confessions, and the assurance that in receiving absolution and the amendment of life, one has been granted the grace needed to move forward.

It does not take much reflection to recognize that every one of these assumptions are missing in the definitions of sin and guilt that are so common today. Though the word “guilt” is often used, shame is what is intended. Confession is required, again and again, but absolution is never in the offing. And no one can be assured of making a healthy confession grounded in the choices that they have made or of finding a way forward.

When so many differences up-end the logic of an ancient spiritual practice, it becomes clear why sin and guilt have made comeback. They are tools of division, manipulation and power, not healing and redemption.

[1] Karl Menninger, Whatever Became of Sin (New York: Hawthorne Books, 1973).

[2] Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Race (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018).

[3] Libby Copeland, “When Guilt Is Good,” The Atlantic, (April, 2018):

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/04/how-to-guilt-trip-your-kids/554102/

[4] Ge 3:1-11, Eugene H. Peterson, The Message (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2014).

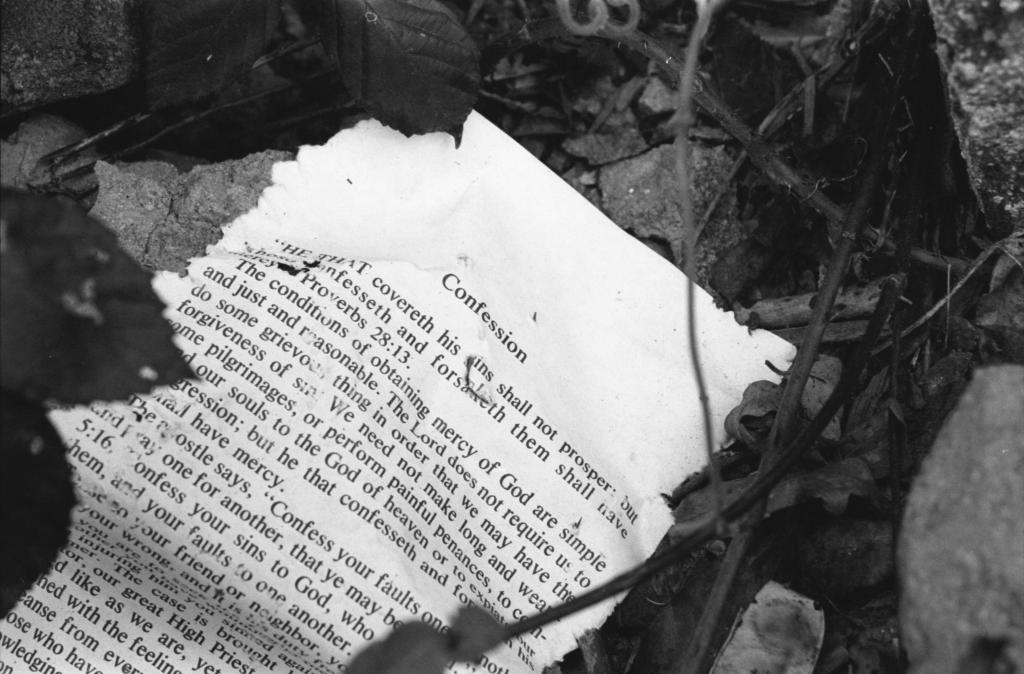

Photo by Julio Rionaldo on Unsplash