This article continues a series “On Being the Church.” But allow me to begin by reminding us why we are talking about the church at all.

One: Because the church is God’s instrument of salvation. Two: Because the church is the place where our relationship with God and with one another is healed. Three: Because the church is the body of Christ. And four: Because we can’t walk away from the church without walking away from Jesus.

It’s just that simple.

But in another way, it’s not simple at all. Because that healing can’t take place without our participation in the Holy Spirit’s work through the church and that requires the investment of a lifetime.

We might want to avoid that conclusion. We might think that holding onto a belief or two about God will make all the difference. We might think that believing in God and living a “good life” is enough. But that’s not what the Christian life is all about.

The Gospel is not about being good. It is about belonging to God, about becoming more deeply shaped and motivated by God’s view of the world, God’s view of our lives, and God’s view of the lives of people around us. To put it another way: It’s about becoming more and more deeply acquainted with God’s hope for us. And that’s not a simple process. If God is infinite and I am finite – if God is the essence of truth, beauty, mercy, and grace and I can be dishonest, ugly, uncaring, and judgmental – then becoming more like God is not something once and done.

I certainly thought that the “be good version” of the Christian life was enough as a teenager. I agreed with the Apostle’s creed. I did my best to be a good son, a good student, and I worked hard to prepare to be a good adult.

But truth be told, God didn’t really have anything to do with it. What I took to be good was a ragbag of what I had inherited by way of values from my parents and from society, and I didn’t really need God for any of that effort. God was just window dressing for what I believed anyway.

What I was living into was basically what Theodore Dalrymple calls the “American cult of sentimentality.”[1] A highly personalized set of values without grounding in anything larger than my own experience and what makes me feel good about myself.

If you wonder why we are such a deeply divided country, if you wonder why people can value such different things, if you wonder why people have such very different versions of the truth, if you wonder why people can justify and condemn behavior that is destructive – if not baldly evil – the cult of sentimentality – this fixation on ourselves – has a lot to do with it.

We live in a culture that no longer asks why are we here? What is God’s will for us? Or what is the purpose of human life? We are not accountable to anything bigger than ourselves, and we regularly cut ourselves off from relationships that do not fit our vision of ourselves or our needs.

Instead, as sociologists have noted for some time now, the only questions we ask are focused on the individual and what is meaningful to the individual. So, we talk about my life, my work, and my goals. It shouldn’t really surprise us, then, that others make choices that are diametrically opposed to the ones that we make. Uprooted and isolated, we go about living our lives, doing our jobs, and at the end of the day we open the garage, park the car and disappear behind the walls of our homes. Modern suburbia is not a community. It’s an infrastructure.

That emptiness and isolation is now on display across our society. Churches are emptying out because people argue it just doesn’t meet their needs. Parents rear their children on one set of values only to have the colleges that they attend teach them a completely different set of values. Politics have become a substitute for faith in God.

Into the middle of that malaise come the words of Paul: “So then, brothers and sisters, we are debtors, not to the flesh, to live according to the flesh– for if you live according to the flesh, you will die; but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live. For all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God.” (Romans 8:12-14)

These are strange words, and they are strange enough that most clergy no longer preach from them. They sound as if they are world-denying. They sound as if they are a condemnation of the body. And – to the ears of the sentimentalist – they are just a buzzkill. It’s this kind of language that regularly gets Paul condemned – even by so-called Christians.

But Paul is not condemning the body, nor – if it concerns you – is Paul condemning sex. Paul is a good Jew, as well as a follower of the Resurrected Christ, and he believes that creation is the good gift of God, including our bodies. What he means by living “according to the flesh,” is a life lived without reference to God, without attention to God – life lived as if God does not exist and as if God had not died for the church.

So, I hate to break this to all of us, including my 18-year-old self, but any life lived in accord with some version of sentimentality is just as much “life lived according to the flesh” as a life lived in accordance with values that we would condemn as morally reprehensible.

Don’t misunderstand. I am not suggesting that it is just as bad to live a life shaped by private goals as it is to live a life given over to criminal behavior. But I am saying that neither version of life is life in the Spirit.

You see, what Paul understood is that what gets our attention gets us. And – if we live without a deep connection to God and to the body of Christ – then something else will get our attention. It might be something destructive, like addiction, porn, sex, or violence.

But that thing might also be a “good thing” in the absolute sense of the word. If it is not ordered and shaped by a conversation with the God who gave us that good thing, then it, too, can become our god. And as a result, even a good thing can become a bad thing.

For example, it’s a good thing to be a parent. But parents for whom parenting has become their god often destroy relationships with their children. They indulge their children too much, leaving them unable to navigate the world on their own. They can be desperate to befriend their children to the point that they are unable to guide or to discipline them, making their children unlovable little tyrants. Or they can so define themselves as parents that ultimately, they can fail to let go when their children become adults, simultaneously smothering their children and driving them away.

A career can be a great space to express ourselves. But that depends upon getting a job where that can happen. And even if we do, jobs come and go, they are interrupted by illness and unemployment, and eventually we all retire. When people let their work define them more often than not, they experience retirement as a life-ending event and that is also why – along the way – their interest in their careers can eclipse their relationships with spouses and children.

I should note that clergy can do these things just as surely as laypeople. A.W. Tozer, the great Christian Missionary Alliance pastor, wrote books on the spiritual life that are still reprinted and widely read. But Tozer neglected his family and when he died, neither of his children were Christians and when his wife remarried, she declared, “A.W. loved the Lord, this man loves me.” Candidly, I am sure she was wrong. A.W. probably loved being thought of as someone who loved the Lord. The Lord would have pointed him back to his responsibilities as a husband and as a father.

This pattern is also how politics have become the substitute for faith in God. If we give up asking what God’s will for us is, the questions, “Why are we here?” and “How, then, shall we live?” still remain. So, people who used to think that fundamentalists were the only ones who preached fire and brimstone – or who were willing to send people to hell – now send others to hell for their politics. Friendships, marriages, and families are divided by it. Members of both political parties condemn one another and call one another names. And the violence has spilled out into our cities and streets and across the internet.

What Paul points out, is that when we live in the Spirit, we are no longer enslaved to these obsessions and others, be they good or bad. Destructive forces fall to one side. Good things find their proper place and role. God isn’t trying to rob of the gifts that he has given us. God longs to help us order those gifts so that we can experience true freedom.

My 18-year-old-self came to grips with that realization the hard way. I had been working hard to be a “good person,” rather than allowing the Holy Spirit to make me “God’s person.” There was very little grace in that world for me and only a little bit more for others. Nothing was ever perfect enough.

Then, in the middle of my senior year, I was in a terrible accident that put me in the hospital for 28 days and, after that, in a wheelchair and hospital bed for several more months. The experience forced me to ask what the purpose of a life could possibly be lived out of a fear of failing and why I thought that God could possibly want that for me. It took time – a lot of time – to come to grips with the freedom that God was offering me, rooted in the knowledge that God loved me – not the perfected me that had become my private God.

But years later, I can tell you that it is the church’s sacraments, prayer and fellowship with other Christians, and the joy of sharing that love with others that keeps me grounded in that grace. Without the work of God’s Spirit through the church, I am certain that my inner 18-year-old would have found new clothing and new reasons to go on living in fear of failure.

It is my prayer that you will receive the Spirit’s invitation in your own life, discover the grace that Christ longs to share with you, and join us in our shared journey into that freedom that exists in Christ alone. That is the promise of life in the church. That is the journey we are on. That is the journey into which the Spirit is inviting you.

[1] The phrase is one coined by Theodore Dalrymple. The definition is mine. His is also helpful: “sentimentality requires the attachment to a distorted set of beliefs about reality, and also the fiction of innocence and perfection, either actual or potential.” See: Spoilt Rotten: The Toxic Cult of Sentimentality (London: Gibson Square Books, 2011).

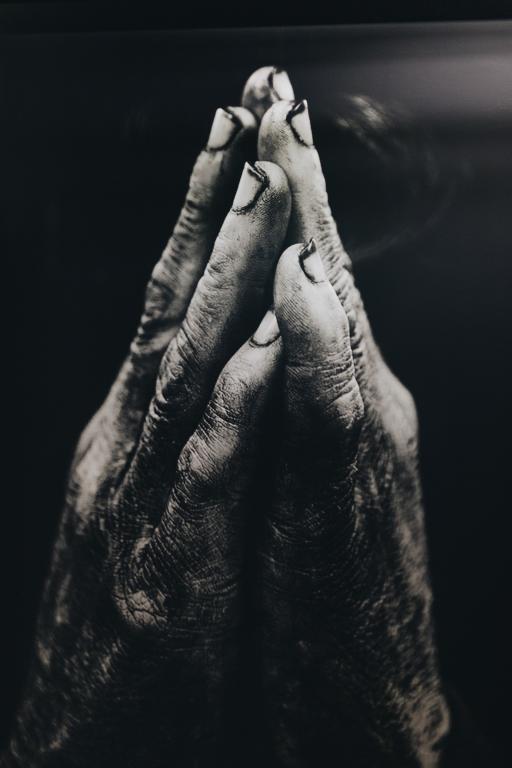

Photo by Kevin Pire on Unsplash