In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

There was a man sent from God, whose name was John. He came as a witness to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. He himself was not the light, but he came to testify to the light. The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world.

He was in the world, and the world came into being through him; yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him. But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God.

And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth. (John testified to him and cried out, “This was he of whom I said, ‘He who comes after me ranks ahead of me because he was before me.'”) From his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace. The law indeed was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known.

John 1:1-18

I am a sentimentalist. When Christmas rolls around and we get the trees decorated, I turn the lights on every morning. I walk outside just to take in the lights on the front of the house. We drive around our neighborhood taking in the lights on other people’s houses (except for the guy with the 25 inflatables). I play Christmas music and I have a litany of Christmas movies to watch, the most sentimental of which are “It’s a Wonderful World” and “White Christmas.” Some of my fondest memories from childhood was the faint glow of the Christmas tree that my parents assembled after we went to bed and blocked from view with a bed sheet over the entrance to the den.

As attached as I am to those memories and to the annual rituals, they have nothing to do with what I believe Christmas is all about. Nor do they have anything to do with why I celebrate Christmas. If they did, I must confess, there wouldn’t be anything but sentiment to justify giving any time to its celebration, and I probably wouldn’t bother.

Now most of the Gospel stories find it difficult to resist the sentimental side of our celebration. They are inhabited by sheep and shepherds, wise men, and a baby. Though, truth be told, if you get in touch with what those stories meant in their ancient Jewish context, none of those sentimental interpretations would hold up to scrutiny.

But of all the Gospel texts that we read at Christmastide, the reading from the first chapter of John’s Gospel completely avoids the pictures that we have smothered with two millennia of sentimentality. Apart from the passing reference to John the Baptist, there are none of the characters that dominate the other gospels. There are no shepherds or wisemen. There is no reference to Herod, or taxation, to Elizabeth or Mary, to Nazareth, Bethlehem or to a babe in a manger.

This is not because John did not know these stories or disagreed with the point that the other evangelists were trying to make. It is because he has a different point to make. So, rather than tell us the stories of Jesus’ birth, John starts at the other end of the story or one might even say the “origin story.” We are told, up front, that Jesus is the Word – the mind and purpose of God. That the Word is God, and that the Word was present at the very beginning of creation.

In an effort to explain the significance of this truth, the Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard tells a charming story of a young prince who was looking for a maiden that might serve as his queen. As Kierkegaard tells the story the prince encounters and falls in love with a beautiful young peasant girl, but the differences in their status poses a problem. If he cannot command her to love him, because – by definition – love is voluntary in nature, and he cannot reveal his true identity, because he will never know whether her love is genuine. So, instead, he decides to assume the life of a peasant, living as they live, working as they work, and struggling as they struggle. And by loving her first, she eventually falls in love with him.

The story goes a long way toward explaining John’s point, but like all stories it can only explain so much of what John is trying to say.

Jesus is not just our King, he is our creator.

We aren’t here waiting for his largesse. He is not here to impose his rule upon us, as if we are here by virtue of our own power. He is the one who made us, who blessed us with the capacity for love and relationship. And, as John observes, he comes among us to restore that capacity in all its fulness. This is why John uses images like the vine and branches, the concept of indwelling and friendship.

If you struggle with childhood impressions of the Christian faith that have lost that thread of the Gospel story, I invite you to consider anew, what the promise of Christmas is really all about. The coming of Christ is not the story of a fault-finding God, who seeks to impose an alien set of values on your life or seeks to crowd out joy or delight.

It is the story of a God who made us for joy and delight, which is the fruit of a loving relationship with God and with our neighbors. And Jesus came to live among us to restore the gift that is native to our very being – the heart of what it means to be made in the image of God.

Another point that the story of the prince does not quite capture is the emphasis John places upon the healing of not just humanity, but of the whole of creation.

The prince falls in love with his bride and instills a love for him that would not exist without his efforts. But John wants us to know that what is at stake in the birth of Christ is not just the claim that Jesus is Lord, but that God is the creator.

By contrast, John is clear: It makes no sense to believe that God is creator, if God abandons creation to the power of death. And the Word is unwilling to make that concession. So, the prince’s loving sacrifice reaches far beyond the relationship with his bride, even if we think of the bride as a stand-in for you and me. God’s love embraces the whole of the created order.

If you struggle with approaches to the Christian faith that suggests God is without care or concern for the world, or that God loves everyone, but has special friends, rest assured, that is not the case.

And, finally, know this. The Prince of peace is with us in the brokenness of the world that we live in this night.

John offers his version of the Christmas story out of its beginnings. But he is under no illusion that the world into which Christ comes is remotely perfect or at peace. It is broken and desperately broken in many ways. That is why he talks in terms of the light and darkness, truth and the willful refusal to receive the truth.

If you are a sentimentalist, like me, you are painfully aware that it is hard to stay sentimental. Almost every Christmas is tinged with sorrow. Almost every relationship we nurture is imperfect. Almost every year brings loss. And – even if we have an occasional year when that is not the case – an honest reading of human experience tells us that is not the case for our brothers and sisters, next door, across town, or around the world. And that is why sentimental feelings can never suffice as a basis for navigating life and why sentimental messages evaporate so easily in the light of day.

So, if you are convinced that Christians are people who live in denial or who are free to wrap a warm blanket around them in blissful ignorance of the world’s pain – or if you came with your own sorrow and loss, feeling that there is nothing to celebrate – know this: The babe in the manger is not a simple infant and the object of facile adoration.

He is the vanguard of God’s redeeming love, offered in a world that is in pain. Capable of taking that pain upon himself. Capable of standing alongside of us in our own loss. Capable of conquest by the strangest means known to humankind: the conquest of sin through the One who was without sin, the conquest of sorrow by the Man of Sorrows, the conquest of power by the Prince of Peace, the conquest of death through the One who dies, the conquest of hatred through the one whose name is Love.

To whom be glory this day and forever more. Amen.

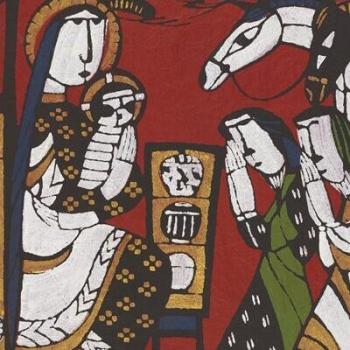

Photo by Mourad Saadi on Unsplash