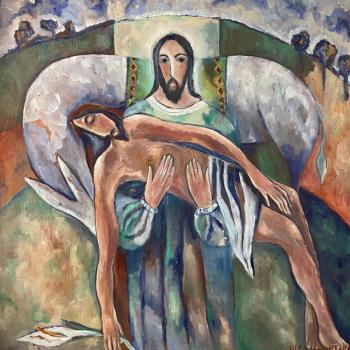

13 There were some present at that very time who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. 2 And he answered them, “Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans, because they suffered in this way? 3 No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. 4 Or those eighteen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them: do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others who lived in Jerusalem? 5 No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.” 6 And he told this parable: “A man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard, and he came seeking fruit on it and found none. 7 And he said to the vinedresser, ‘Look, for three years now I have come seeking fruit on this fig tree, and I find none. Cut it down. Why should it use up the ground?’ 8 And he answered him, ‘Sir, let it alone this year also, until I dig around it and put on manure. 9 Then if it should bear fruit next year, well and good; but if not, you can cut it down.’” (Luke 9:1-13, ESV)

For a while there was a popular little practice in Episcopal parishes called “stump the priest”. It was usually pursued in adult formation classes — more often than not on a Sunday when the clergy had failed to prepare anything else. This little parlor game was a variation on open-mike hour, in which parishioners were invited to ask their priest any question that occurred to them. There always seemed to be a variety of motives behind the questions: Some were asked in an effort to really learn something, some in an effort to finally resolve a nagging problem, some to make a point, and some in an effort to do exactly what the name of the game was really all about: stump the priest.

I never really understood the point of this game. In part because it made some truly silly assumptions about what a priest knows. But, also, because in my experience, there were enough “stump the priest” moments in a priest’s life anyway.

That seems to be exactly what Jesus faces in Luke’s Gospel. No “open mike”, no formal program. Just people puzzling over the significance of things that were happening around them. But still a case of stump the priest or – in this case – stump the Messiah.

In this case, the event weighing on their minds seems to be the news that a group of Galileans fell foul of Pilate and ended up getting killed on their way to offer sacrifices at the Temple. We don’t know any more about it than that and the fact that this kind of thing probably happened on more than one occasion. But what people seem to have asked Jesus took the form of a rhetorical question: “These are signs, aren’t they? These things happened to them and not to us, so we must be righteous and they weren’t.”

This was and is an age-old assumption: “Good things happen to good people. Bad things happen to bad ones.” They were not the first to make this assumption and they were certainly not the last to think this way. Job’s comforters are basically this line of thought on steroids. And just in my own lifetime, I’ve encountered people who think these things or who think things that closely approximate this line of reasoning.

Years ago, I wrote a book entitled When Suffering Persists. After it was published, I made a number of presentations based on the book that were designed to help Christians think in a faithful, compassionate, and theologically credible way about the problem of suffering.

I was prompted to write it for both personal and pastoral reasons. I knew firsthand and worked with far too many people who had been told truly hurtful things by people I knew were trying to be helpful. But I also knew that people who offered that help often said things that were ill-informed and shaped by assumptions that were anything but biblical or Christian in character.

One of the points I made back then and still do, is that God is not the author of mayhem, misery, illness, and misfortune. We may occasionally bring it on ourselves, as in the case of life-long addiction or cruelty to others. Choices have consequences and there are characteristics of life that, like the law of gravity, cannot be ignored. At other times, we often visit misery on others, as in the case of murder and senseless wars. And, perhaps even more often, suffering just happens, as in the case of accidents, earthquakes, and cancer. But God is never its author.

Apart from the fact that it is a misreading of Scripture to assume that God arbitrarily torments people, the other difficulty with that kind of thinking is that it makes God a moral monster – particularly in the case of random suffering. The notion that God singles out one person for cancer, another for a heart attack, and lets still someone else live a long and carefree life is akin to thinking of God as someone who carries out cruel and pointless experiments on animals or small children. And being bigger doesn’t make that kind of behavior more moral.

The other thing that I often said – and still do – is that God doesn’t “permit” or “allow” specific kinds of suffering to happen. This has often been a fallback position for people who want to believe that all suffering is somehow fated to happen, but who recognize the moral problem with suggesting that God targets people for suffering. “God didn’t will this to happen, but he allowed it to happen,” so the distinction goes.

The problem with this approach is that very little more than a semantic difference between saying God willed something to happen and that God selectively allows things to happen. I may not force my child into traffic, I may allow her to walk into traffic. But I am certain that child protective services would not be impressed with the distinction.

I understand why Jesus’ contemporaries and Job’s friends thought this way. And I understand why people think this way even today. All of us struggle when we see other people suffer.

In part our desire to find an easy explanation arises out of what the Germans call, Schadefreude, or shame-joy: that strange, conflicting feeling of both relief at having escaped the misery that others encounter and the shame we feel at our joy or relief. At some level we know that others don’t deserve to suffer, and we also know that we don’t deserve to get off “scott-free”.

So, we resort to the assumption that God is behind it all. It relieves us of the task of examining our own lives and behavior. It spares us the need to show compassion to those who labor under their misfortune, and it buys us the emotional distance that allows us to get back to our own lives.

On another level it appears to make sense of events that don’t make any sense. We stitch together the idea that God makes or allows suffering to happen with the assumption that God must have some hidden purpose in making it happen and, suddenly, we can wrap a narrative around an experience that doesn’t seem to have a point. “God did this to test your faithfulness, to strengthen you, to work through you, to touch others.” And we can point to just enough examples of people we have met where those things have happened that it all seems plausible.

Making the rounds through a number of churches talking about my book, I met a couple who believed this for exactly those reasons. I had been describing the problems with suggesting God causes suffering and the longer I talked, the more clearly one couple became angry with me. I could see it in their eyes, on their faces, and in their body language. If looks could have killed, as they say, I would have been dead.

They never gave me a chance to address their concerns. They eventually stormed out of the room one day, and I would have never known what was troubling them if one of their friends had not taken the time to explain. But one of their friends stayed and explained: Look what made them angry is that they were infertile, and they had never been able to conceive a child. So, they concluded that God had made them infertile, so that they would become foster parents. They are loving, wonderful parents and they have already fostered twelve children, but their whole explanation for their lives and their love revolves around the conviction that God made this happen.

I wish that they had given me the opportunity to address their concerns. If I had, I would have told them: Look, I think what you are doing is wonderful, and I am so impressed that you have used your suffering to address the suffering of the children you have loved and brought into your home. But allow me to suggest to you that rather than blaming God for your suffering and the suffering of the orphaned children you have welcomed into your family, you might think of it this way: God did not do this to you or to them, but you have done what Jesus does on our behalf and addresses their suffering out of yours. This is the way and you have been faithful in the shadow of the cross.

I have no idea how the crowd responded to Jesus. I would not be surprised if people walked out on him as well. When he found himself in the crowd’s game of “Stump the Messiah”, he told them no, they weren’t more righteous than those who suffer, and he upped the ante by offering a second example of people killed in the collapse of the tower at Siloam. Instead, he tells them what we all need to hear: We are not better than others. The balance of fortune and misfortune in our lives is no measure of our virtue. Draw close to God. Seek his forgiveness. Receive his mercy. Put your life in God’s hands.

Let us pray:

Gracious and merciful God, you love us more than we love ourselves and you love our neighbors with the same, enduring love. Too often we prefer to judge our neighbors. Too often we weigh our fate against the fate of those around us, relying on our own merit, rather than leaning on you. Too often we prefer the certainty of our assumptions about your will, rather than trust you and place ourselves back into your hands. Guide us as we seek to live and love in the shadow of the cross, that we might give ourselves to you and to others in loving availability in both good times and in bad. Through Jesus Christ, our Lord, who with you and the Holy Spirit, reign one God, now and forever. Amen.