“The women were terrified and bowed their faces to the ground, but the men said to them, ‘Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here, but has risen.’”

I came back from Oxford in 1986 and served a small church that stood all on its own along side the parsonage, seven miles south of Kingsville Ohio. Gageville United Methodist Church is just south of Lake Erie in lake-effect snow country, and I lived so far from my neighbors that the only way they could reach me was by telephone or high-powered rifle.

I was a city kid. But I threw myself into life there. Listening, asking questions, and fishing for walleye in Lake Erie with members of the church. I loved them, they loved me, and I am still in touch a few of the people who live there.

It’s strange what sticks with you from an experience like that, even after decades pass by. Despite the adjustments that I experienced moving from suburban and urban communities to a thoroughly rural setting, the adjustments don’t figure prominently in my memories. Instead, the one challenge that still lingers with me after all these years wasn’t about geography at all, but about something universal and deeply human.

You see, thanks to a nearly endless amount of time in school, I had never officiated at a funeral and, in the space of a single year, I did nine of them. But more precisely, the thing that stuck with me was how hard it was to care for the families of people who had little or no connection with God or their church. There was the young father who worked in Ashtabula and who had a wife and two daughters. He died from smoke inhalation in an industrial accident in the harbor, trying to put out a fairly minor fire on a coal conveyor over the harbor. And there were several people that the local funeral director asked me to help who had no connection to any church anywhere.

I’ve spent a lot of time wondering why those experiences made such a lasting impression and why they were thread through with so much sorrow for the people involved. I am sure that it was partly a matter of taking responsibility for so many funerals all at once and for the first time. But that was not the really the issue. I don’t remember the funerals of people whose lives were deeply shaped by the love of God with the same kind of sorrow.

Eventually it became clear to me that what troubled me was the difficulty in helping those families to find any meaning or comfort for themselves in the face of their loss. The husbands and fathers who died had gone to elementary school and high school. Some of them went to college. They had found jobs, married, bought homes, and had children. They laughed and loved, went to work, paid their bills, shopped for groceries, and made endless trips to Home Depot. Some of them even made it to an advanced age.

Now you might suppose what made me sad was that somehow I thought that they weren’t good people, but they were. Or you might suppose that what made me sad was that they weren’t active in the church or that I couldn’t say “they were going to heaven”. But I never focused on their absence from church, and I avoided making any pronouncement about their lives or their eternal destiny. I felt no need to do that. That is God’s call, not mine. In fact, to the extent that I focused on what lay beyond the grave, I emphasized the promise of the Resurrection, and I reminded them that God is loving, gracious, and dependably good.

In truth, what made me sad – on their behalf – was that there wasn’t a thread that held their lives together. All they could do to console themselves was to remember good times that they had together, remember the good things their loved ones did, and laugh about the funny things that happened along the way. But behind those frail memories lay an awareness that one day the people who remembered them would no longer be around to tell and retell those stories.

There was nothing that gave their lives an enduring meaning or focus. No motive that was larger than the microcosm of their life as a family. Nothing that pointed beyond their lives to a larger reason for living or pointed their children to something that lay beyond their lives. And it was that – that emptiness – that made me sad. To play with the words of the two “men” at the tomb that Luke describes, you might say that the families I cared for had no choice but to look for the living among the dead.

So, if you take anything away from this celebration today, this is what I long for you to hear: The Resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead is not – in the first place – about what happens to us on the other side of the grave, though the hope of eternal life is a reality. The Resurrection of Jesus Christ is not about the fear of dying, though it speaks to that fear.

It is about a present tense reality. It is about the transformation of our lives. It is the gift of purpose and meaning that makes eternal sense out of lives that are mundane. A gift of purpose and meaning that is larger than our individual lives. A gift of purpose and meaning that endures suffering, loss, and the grave.

The story of Christ’s Resurrection is the story of one who is fully alive, fully present to his disciples, and one who calls his disciples to live in a radically different fashion. A life that flows from the living Christ — moves toward living Christ — draws strength and direction from the living Christ. It is a tragedy that there is so much out there in terms of cultural and religious messaging that makes this hard to hear.

Some of that blame falls on the church:

Fundamentalists have reduced the Good News of the Resurrected Christ to eternal fire insurance. And it is a small wonder why people scoff at the way that message is delivered, arguing that the church is just trying to stampede people into the arms of God, using fear and duress.

The preachers of the health and wealth Gospel have distorted the Good News of the Resurrected Christ by implying that the Risen Christ is the guarantor of the promise to make you healthy and wealthy. So, it is no surprise that some run from the church, convinced that all it promises is a religious justification for the consumer-oriented world in which we live and that the church could care less about the poor.

By the same token, however, the preachers of Progressive Protestantism have distorted the Gospel by suggesting that the Resurrection is a metaphor for a new political order — which is why still other people find it hard to grasp just how important the news of the Resurrection is to their lives. They are justly suspicious that – presented in that fashion – the Gospel is just another brand of politics offered up in religious costume.

But it is also hard to hear the good news of the Resurrection, because new atheists and the church’s detractors offer up lies about the promise of a life without God:

Read as many of them as you like and I’ve read a fair number of them, and you come away with the inescapable conviction that atheists and agnostics are not really honest with themselves or with anyone else. They try to suggest through a sleight of hand that life has meaning and there are moral values that govern life – or should. But in a cosmic vacuum where there is no God and one in which our lives and the lives of everyone we love are an accident waiting to be extinguished, they are never willing to acknowledge that such convictions are pure fiction.

In the world of atheists and agnostics there is no meaning-making that lasts. No moral principles to which anyone is obliged to observe. No life that isn’t dust. Such efforts are, at best, futile gestures and, at worst, a cruel joke.

But there is one more hard thing I need to say. One more thing that makes it difficult to hear the Good News of Easter:

No matter how badly we have done in explaining the hope of the Resurrection and no matter how much nonsense has been offered in its place, the other thing I have had to face in my own life and the one thing that we all need to face, is the resistance to the Good News of the Resurrected Christ in our own hearts. It may sound strange to say that the offer of meaning, purpose, hope, and joy can be hard to hear, let alone accept – but it is.

It is because the Resurrected Christ calls us to follow him. He calls us to hear him. To place him at the center of his life. To love what he loves and care for those for whom he cares. And that always threatens to up-end our lives. Not just in big ways, but in a thousand small ways: simply by asking ourselves what we would do differently if we are now – and always will be – in the presence of the Lord of Life.

The longer we sit with that possibility the more the questions multiply: Would we be a bit more honest and vulnerable? Would we be more loving and self-giving? Would we be more generous with others and with everything that God has given us? Would we be less self-absorbed? Would we look beyond our lives to the purposes of God in our world? Would we be willing to risk ourselves or talk a bit less about our boundaries and our goals? Would we be more likely to forgive and love, rather than judge and hate?

We would undoubtedly do all of those things and more, because this way of being is reflected in the life and death of Jesus. And the Resurrection is God’s “yes” to all that his life tells us about the nature of God and God’s purpose for our lives.

But it is all too easy to be content with so much less. To live with our brokenness, anger and envy, or to simply let days slip by us, one after another, unaware of their emptiness. My hope is that you will not surrender to that temptation, but say “yes” to God’s “yes” that we celebrate on this Easter Sunday. To do that is what it means to stop looking for the one who lives among the dead and give ourselves completely to the One Who Lives.

The Lord is Risen. He is Risen Indeed.

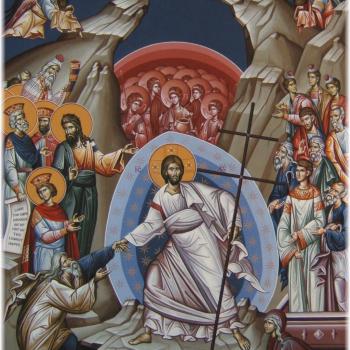

Photo by MohammadHosein Mohebbi on Unsplash