Woody Allen best captures the modern, American attitude toward death: “I’m not afraid to die, I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”[i]

But if denial is the dominant approach to death, our other approach to it involves a wide array of rationalizations:

“He lived a full life.”

“It was a blessing in disguise.”

“It could have been worse.”

“It’s all a part of life.”

The list is endless.

Some of the rationalizations are intelligible, of course, at least in narrow terms. A painful illness that may have lingered and is cut short by death may be “a mercy”. A long, full life is, all things considered, preferable to a short one. If one dies on behalf of others, there is reason to believe that one has died “in a good cause”.

But such rationalizations are only true in narrow terms. Measured against the ideal, death is always a tragedy at some level. All things considered, the longer we live, the more attached we are to one another. A full life is still a life ended. A trying illness cut short by death is still a life cut short.

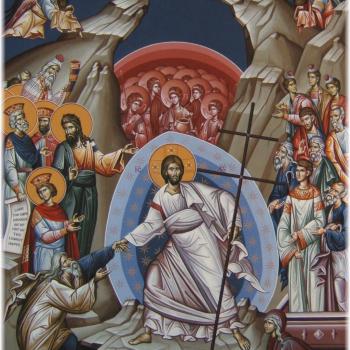

It is this dis-ease with death, its unfinished, disruptive, and unwelcome character, that Scripture names, whether it is in the Psalms or Wisdom Literature, the Gospels or the Pauline Epistles. According to the biblical witness, death is neither “natural” nor is its “God’s will”. It is a contradiction to God’s claim to be the author of life. As I have noted elsewhere, this is why the Resurrection is so important in the Christian faith and why it is about far more than what happens to us on the other side of the grave. The Resurrection is a vindication of God’s claim to be the Lord of life and a vindication of the claim that the death of Christ is the divinely chosen path of redemption.

But it also has implications for those who grieve the loss of those they love:

One, Christians are not, by definition, people who are unmoved by death.

Yes, as Paul observes, we do not grieve as people without hope, but we do grieve.[ii] We grieve because we are human. We grieve because we are made for relationship. We grieve because to love deeply is to experience deep loss.

We also grieve because, in Christ, our relationships with God and with one another are healed and deepened. But even though that healing is already in motion, it is not yet all that those relationships will be. For that reason, it is natural, even inevitable, that we experience the presence of death as a source of grief.

Two, as Christians we grieve because we truly understand what it means to live.

Other religious traditions elevate attachment as the central spiritual challenge. That is certainly what Buddhism teaches. In a sense that conviction lies at the heart of Stoicism (of which there are a growing number of modern adherents).

Not Christianity. To be sure attachment, especially to riches or to a life lived selfishly and for one’s own sake is a problem – to say the least. But life in Christ is about ordering our attachments and about the healing of relationships. Life in Christ is about the healing of relationships with God and with others, and death challenges that promise. As Henri Nouwen notes, for that reason a Christian is aware that death is a “dark contradiction” and at odds with God’s longing for us.[iii]

Three, Christians should be gentle with themselves and recognize that, in Christ, God grieves with them.

If Christians grieve because they are in touch with what it means to live, then they should also be gentle with themselves as they grieve. It is worth knowing, too, that Jesus grieves with them.

The moving portrait of the raising of Lazarus describes one of the rare windows into the emotions Jesus experienced and describes him as weeping at the news that Lazarus has died. Interpreters have noted that the description may suggest just how much Jesus loved Lazarus, and that is undoubtedly true. But others have noted that it may also reflect the grief Jesus felt at the prospect of bringing him back to life, knowing that he would die again.[iv]

The story is also a powerful window into the solidarity with our grief and loss that Jesus forges with us in the Incarnation. Why is this important?

Paul, as I have said, does not tell his churches that they should not grieve, but that they should not grieve as those without hope. The Book of Revelation foresees a new heaven and new earth in which the Resurrected Christ wipes away every tear, which presupposes that grief is a natural reaction to loss.[v]

The same is true for us, of course, and pastors should push back on those who claim that grief is something that is inappropriate or that grief is something that people should “get over”. To be sure, it is important not to become stuck. In the wake of loss it is important to “relearn the world”.[vi]

But relearning the world is not a predictable, linear process and it makes little sense to talk in terms of “getting over” the loss of those we love. It makes more sense to accept that – only over time – we fold that loss into our lives. We acknowledge it, and we find a way forward, assured that – thanks to God’s gracious intervention – no good gift is forever lost.

[i] Woody Allen, Without Feathers (New York: Ballentine, 1986).

[ii] I Thessalonians 4:13-14.

[iii] Quoted in: https://www.patheos.com/blogs/whatgodwantsforyourlife/2022/04/the-last-seven-words-of-jesus-my-god-my-god-why-have-you-forsaken-me/

[iv] The Lazarus story is one of resuscitation, and while it foreshadows the Resurrection, Lazarus is not raised to eternal life.

[v] Revelation 21:4.

[vi] Thomas Attig, The Heart of Grief: Death and the Search for Lasting Love (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Photo by Danie Franco on Unsplash