“The voice of one crying out in the wilderness:

‘Prepare the way of the Lord,

make his paths straight.’” (Mt 3:3)

We read this passage every year during Advent. But the language is foreign to our context.

The only straight roads I have driven are in Kansas, western Colorado, southern Illinois, and a stretch across the panhandle of Texas. There is no such thing as a straight road in Tennessee, and anyone who has ever lived in Chicago (as I have) knows that roadwork is not about getting anything done or about making anything straight. But here and in the passage that John the Baptist quotes from Isaiah, it’s all about roadwork and kings – actually a king, the king, the last king that will ever matter.

To understand what this passage means, first of all one has to note that John isn’t citing this passage from Isaiah just to achieve a bit of poetic flourish. He is quoting it because it speaks powerfully to his contemporaries and draws on a tradition that had shaped Jewish expectations for millennia.

The Israelites had carved out an existence in the middle east where they were constantly surrounded by hostile powers. They lived on the western end of the fertile crescent, which had been the road to war in the region for as long as anyone could remember. As a result, they had been conquered, exiled, and occupied so often that stability, safety, and security were dim memories, the stuff of legend. Kings and – in particular – David’s reign were emblematic of the hope that someday they would experience that kind of safety again. David was to the Israel of John’s day, what Arthur and the knights of the Round Table were to the English of a later era. So, his use of the image tapped deeply with their dreams.

John also quotes these words from Isaiah because it spoke powerfully to the Jewish people about the way in which they had tried to save themselves and how poorly that had worked out. If your neighbors are beating you – over and over again – you inevitably try their approach. And down through the centuries Israel had tried their neighbors’ gods, mimicked their battle tactics, copied their form of governance, and even attempted to make treaties with some of them. Isaiah names the futility of these efforts and points them forward to a hope that a king, the king, the last king that will ever matter is the only real solution.

It would have been clear to John’s audience, then, they were in basically the same position as their ancestors had found themselves in Isaiah’s day. Rome was the new boss, same as the old boss. And they were trying some of the same old strategies to rid themselves of Rome: looking for a king or deliverer who could beat the Romans at their own game, looking for ways to collaborate, or – alternatively – looking for a place to run, hide, and wait for the end.

Over against those strategies, John was preparing his listeners for a king and deliverer unlike anyone they had ever encountered. And he was calling on his listeners to prepare, just as ancient cultures always prepared, for the arrival of the king: roadwork. Valleys needed to be filled, hills need to be leveled, bridges needed to be built. And, in the ancient near East, all of that work not only prepared for the grand entrance of the king, but served as a testimony to his power, might, and wealth.

This, of course, is where it becomes a challenge to know just what John the Baptist or Isaiah have in mind. When the Babylonians and others – including the Romans – referred to a triumphal entry, they had literal roadwork in mind and they did a lot of it. They built real roads, the erected triumphal arches, and grand bridges. And when the king entered the capital, they were often preceded and followed by captives, slaves, and lions on leashes, all emblematic of their power and authority.

But, clearly, neither Isaiah nor John have that kind of king in mind. The rest of Isaiah’s prophecy doesn’t describe this king as the architect of a new political entity; and he doesn’t promise a theocratic political order of the kind that you find in some brands of the Islamic faith.

Instead, he moves from talking about the political realities that Israel faces to the fragile and temporal nature of life. Humanity’s dependence upon God and the universal deliverance that will come with the king’s arrival.

It is no surprise, then, that when Jesus does come, he declares that his kingdom is not of this world. He makes no effort to marshal a new political order. And he tells his disciples to render to Caesar the things that belong to Caesar and the things that belong to God to God.

So, while the renewed lives of God’s people are supposed to reflect a different way of being and while Christians speak out against injustice, they are not the architects of an order that mimics the politics of the world. And there is ample historical evidence to suggest that when Christians do, the results are disastrous. With good reason, when Thomas More described these efforts he entitled his book, Utopia, which means not just an ideal place but – in the Latin – also means, “no place” or “nowhere”. Christians cannot, by definition, neither depend upon rulers, nor rule in God’s name.

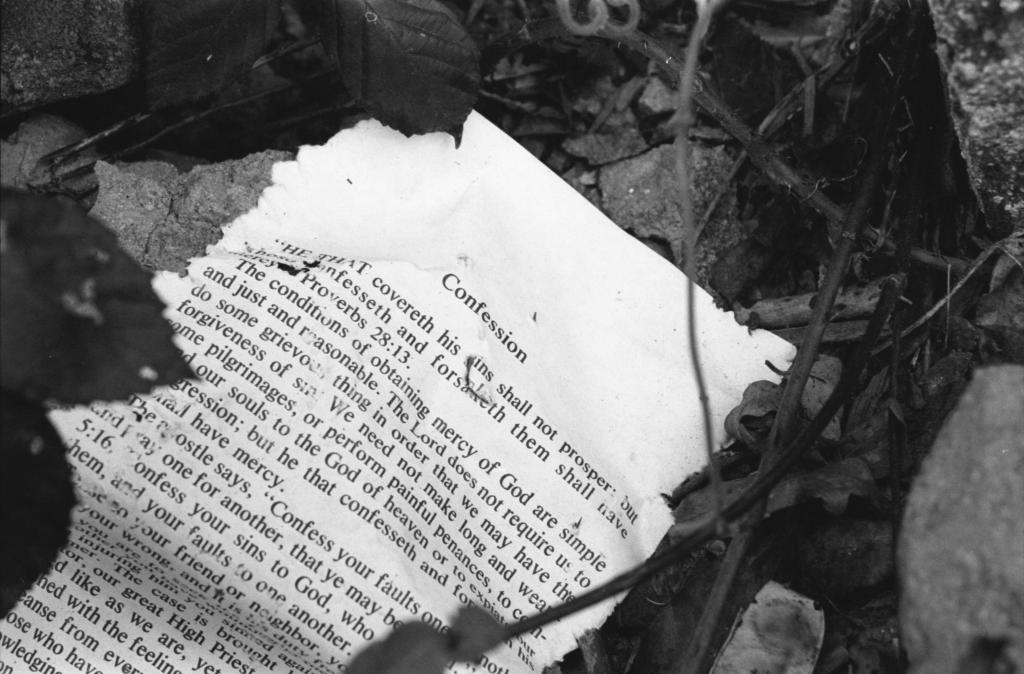

So, what does road work look like and where does the road lead? The clue lies in the picture that the Gospel paints throughout the third chapter. At the heart of the Kingdom’s roadwork is the act of repentance. Clearly, this passage and the rest of the Gospel suggests that repentance is not about self-loathing. It is about being freed, unburdened, opened to the healing work of this one-of-a-kind-king. And for that reason, it is not about a transaction, but about a new path.

Those who repent don’t just surrender the effort to be their own saviors and the grinding burden that entails, they turn and receive the embrace that king offers. And, as a result, they join the king’s entourage, celebrating their own freedom and welcoming still others into his embrace.

This, then, helps to explain where the road leads. It is not a place, but a person. One who identifies with our plight, enters into it, and leads us into freedom. And we are not a part of that procession because we have been conquered and enslaved, but because we have been freed and blessed, given the new opportunity to live into the lives that God intended. And the reign of this one-of-a-kind king makes itself felt wherever there are those who make themselves available to his purposes and give their allegiance to him, because his goal is nothing less than the reclamation of all that he has created.

This is a one-of-a-kind allegiance. The Christian’s relationship with their God is the organizing center of the lives of that they live, and those who understand the spiritual journey have given themselves to this life from the very beginning. Writing early in the second century one writer described Christians this way:

They dwell in their own fatherlands, but as if sojourners in them; they share all things as citizens, and suffer all things as strangers. Every foreign country is their fatherland, and every fatherland is a foreign country. They marry as all men, they bear children, but they do not expose their offspring. They offer free hospitality, but guard their purity. Their lot is cast “in the flesh,” but they do not live “after the flesh.” They pass their time upon the earth, but they have their citizenship in heaven. They obey the appointed laws, and they surpass the laws in their own lives. They love all men and are persecuted by all men. They are unknown and they are condemned. They are put to death and they gain life. They are dishonoured and are glorified in their dishonour, they are spoken evil of and are justified. “They are abused and give blessing,” they are insulted and render honour. When they do good they are buffeted as evil-doers, when they are buffeted they rejoice as men who receive life.

It is worth noting what this description suggests about the Christian life. This is not a road out of life’s challenges. It is not about triumphalism or escape. It is not about being raptured, nor is it about finding comfort in a world that we ignore or that we have bent to our purposes. The final disposition of the world is in God’s hands. What we are welcomed into is a vision of the true purposes of the world and the knowledge that the only king who matters is not of this world. And having entered into his life, we are given the strength of live with the tensions, challenges, and conflicts that reveals.

In this Advent season of prayer and reflection, I invite you to consider what it would mean to acknowledge Christ as your King and name those things that would change in your life, if you did the necessary roadwork.