Over the last few days an article that I wrote, entitled “Whose peace?”, sparked quite a bit of conversation. There were many who agreed and offered their own reasons for agreeing.

Others told me that my position implied that we should have one and only one liturgy. I was also urged to listen to communities and honor differences, meaning — I assume — that I am not sensitive to those communities and differences.

This is not the case. But what those observations make clear is that there are two, fundamentally different assumptions about what is going on in the debate over the church’s liturgy.

One (mine and that of others) is that the liturgy is meant to lift up the saving acts of God in Jesus Christ. Acts that are – across history and across communities – of healing relevance to all people, everywhere. Made in the image of God, we have a common creator, a common need, and we have been entrusted with offering the means of grace made real and relevant in our celebration of the Eucharist.

The other perspective (shared by no small number of people) holds that differences and context are of primary importance. They hold that a message that does not somehow start with those differences, speak to those differences, and celebrate those differences, is (at best) insensitive and (at worst) oppressive.

Inevitably, there are other reasons offered for the countless amendments to Prayerbook that are currently on offer at General Convention. But these are the basic positions and priorities that lie at the heart of the liturgical debate now underway. The one places priority on “the faith once given”, the other places priority on innovation and giving voice to various communities.

As is demonstrably the case, human flourishing requires both impulses. The church identity of the Anglican and Episcopalian traditions depends upon it rooting in the worship and theology that arises out of the Apostolic Tradition. And its effectiveness in addressing human need entails speaking thoughtfully and redemptively to contemporary challenges.

But the question that the church needs to confront is whether the liturgy is the place where the balance between those two impulses should be played out and to what extent the liturgy can do that work. The thesis of this article is that it cannot.

There are practical reasons for that conclusion. One is that human diversity, rightly understood, is endlessly complex and representing that diversity in a liturgy cannot be accomplished. The other challenge is that individuals are never either representative of one community or another, nor are they perfectly representative of the community to which we might naively assign them. I have a Japanese friend, who is married to an Irishman. They are both Canadians. He is the only one who speaks Japanese.

These realities make it impossible for anyone to “see myself” in the liturgy if one has in mind anything more granular than our identity as children of God, made in God’s image. But there is a deeper set of reasons why the liturgy cannot be navigated with this as our goal.

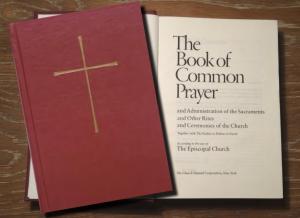

For centuries now, we have been trying to forge a stronger connection with the church’s ancient liturgy. In fact, that effort has been at the heart of what it means to be Anglican.

Recovering that liturgy has been driven by the conviction that such efforts impart life to the body of Christ. They participate in the logic of salvation that empowered the early church. They focus on the work once accomplished in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. And they connect us with the other ancient traditions of the church.

This task of recovery calls for occasional revision, particularly as language changes. But if that process of recovery was and is our goal liturgically, then there is limited scope for revision.

I realize that this conviction is often characterized as unwelcoming and retrograde. The innovative voices in the church argue that for the church to be welcoming, the liturgy ought to give expression to their presence in the church. So, both the logic of liturgy and its language are negotiable.

But that conviction is alien to both the history and the practice of the Anglican and Episcopalian tradition. It overlooks the fact that the grounding in the church’s ancient practice is the denomination’s reason for being. And it fails to recognize that if we walk away from that tradition, we walk away from the charism that the Holy Spirit has given the Anglican tradition.

I believe that the Episcopal church can be both welcoming and faithful to that tradition. The liturgy was forged in the life of the ancient church, long before any of us were alive and long before anything like modern cultures and differences were even imaginable. It is a tradition forged by the call of the Resurrected Christ on the lives of those he touched and on the Twelve; and its power is manifest in the spread of the church and universality of its message.

That tradition was entrusted to us at our baptism. The essentials of our vows are just that – essentials. The latitude, creativity, and innovation we have lies in bringing that tradition to bear in a life-giving fashion on modern challenges and the needs of the world.

The embrace of God does not depend upon our changing that basic message. In fact, the liturgy is meant to affirm the power of God to embrace us. And that embrace lies in being baptized into the body of Christ and in shouldering our cross alongside others.