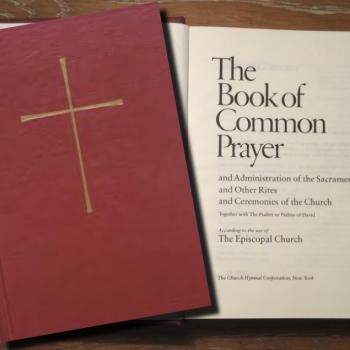

Among the seemingly endless number of modifications to the Book of Common Prayer that are now in the works for General Convention, one of the latest is the proposal that the rubrics allow for extending the “peace” at the beginning of the service. The text of CO36 reads as follows:

The service of Holy Eucharist consists of two parts, the Liturgy of the Word and The Holy Communion. Together they draw the community towards the central act of Eucharistic worship, the sharing of the Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. Linking the two, the sharing of God’s peace affords all the opportunity to set aside our differences, and realize our unity, before approaching the table,

During this time, many enjoy the opportunity to exit the pew to meet and greet those who are present, often seeing for the first time those who are sitting behind them. This is a time of real blessing, yet the Holy Chaos this creates, can distract from the centering actions the Liturgy of the Word affords. Often followed by announcements, the Peace has been described by some as an intermission between the two parts of Eucharist, instead of that which binds them together.

During a clergy sabbatical, focusing on welcoming practices across various Christian traditions, it was noted that communities taking time, as they gather for worship, to welcome one another, seem to gain a deeper sense of unity in their worship and offer a more meaningful experience as the uninterrupted hymns, readings, and prayers of the liturgy draw the community closer together and to their central act of worship. By shifting the sharing of the peace to the start of the service, while offering a prayer for peace following the confession, parishioners have described feeling a greater sense of community in the sharing of the Eucharist, not as a gathering of individuals, but as one body, sharing in the love shared with them.

Believing the liturgy is a means of bringing people together, from wherever they are in life, drawing them even closer together and to God, it is therefore recommended that the sharing of the peace no longer be limited by rubric, but allowed to be shared at the beginning of worship as well.

There can be no doubt that it is difficult to know where to make announcements on any given Sunday. Made at the beginning of the service, many people miss hearing them and people are robbed of the opportunity to prepare themselves for worship. Made at the end, the process robs the service of its liturgical integrity – or at least its energy. Placing them in the middle certainly distracts from the unity of the service, but it is the place where people are likely to hear the announcements. It provides an opportunity to welcome visitors and a bit of guidance can be given on how to receive communion. There is no great alternative and some measure of communication on Sundays is often the only way to reach some people – even with an effective social media program. (Ask our communications director!)

But the resolution repeatedly misunderstands the logic of the service as it applies to offering the peace. This is evident in a number of places throughout (emphasis mine):

- the sharing of God’s peace affords all the opportunity to set aside our differences, and realize our unity

- During this time, many enjoy the opportunity to exit the pew to meet and greet those who are present, often seeing for the first time those who are sitting behind them.

- By shifting the sharing of the peace to the start of the service, while offering a prayer for peace following the confession, parishioners have described feeling a greater sense of community

- Believing the liturgy is a means of bringing people together, from wherever they are in life, drawing them even closer together and to God

Almost the whole of the rationale for this resolution depends upon achieving goals that are either not ours to achieve or which misunderstand the purpose of the liturgy:

- We are not the ones who set aside our differences or achieve unity. These are the work of God.

- The peace is not an occasion to “meet and greet.”

- Feelings are fine, but they are secondary, blessings that flow from the work of God.

- A sense of community is not a free-floating value. It flows from life in the Body of Christ.

- And the liturgy is not about drawing people together. We receive the body and blood of Christ as the body of Christ, receiving (not taking) the healing grace that Christ offers us, which touches both our relationship with God and with one another.

Extending the peace appears in the liturgy where it does, because we cannot offer the peace of Christ without confession and God’s absolution. And we cannot receive the Eucharist until we have received the peace and healing that flows from the mercy of his forgiveness.

It is, from start to finish, Christ’s peace, shalom, restoration, healing — not ours. And it is not an exercise in building community or something that we do, in our own power. It is, from start to finish, the work of God in Christ.

To move the peace to the beginning of any service destroys that logic. And, although it may seem like a small thing to many, changes of this kind threaten to turn our worship into a grab-bag of “experiences”, rather than a prayer that celebrates and draws us into the work of God in Christ.

I am not sure how best to navigate conversations about Prayerbook revision, and at this juncture, I don’t favor it. The long list of revisions before General Convention this month would suggest that we will slowly move away from common prayer to a menu of nice ideas and we will have squandered one of the great gifts of the Anglican and Episcopal tradition.

I am not saying that we should stick with any one iteration of books. I am not suggesting a reprise of the resistance to the development of the 1979 BCP, as the replacement for the 28 Prayerbook. What I am suggesting is that there is a fundamental difference between updating the language of a liturgy that remains grounded in the ancient life of the church and jettisoning that inheritance in favor of a buffet of liturgical gambits.

We can ill-afford that loss in any generation. But we are in a particularly fragile moment to be experimenting with simply looking and thinking liturgically like the rest of mainline Protestantism.

So, whatever we do by processing such discussions, there ought to be a way to ground our conversation in a sound grasp of the church’s ancient liturgy. Otherwise, we will simply have one Convention after another, offering well-meaning but ill-informed changes to our worship, until yet another part of our community grows weary of defending what ought to be obvious.

That process of learning and sifting should be shaped by substantive questions: Whose peace is this? Whose saving work do we celebrate? Who makes this Eucharistic celebration possible?