Throughout the summer, my wife — The Reverend Canon Natalie Van Kirk — and I have been preaching a series on the subject of doubt. We have been addressing both the subject of doubt itself and the questions that are often the source of trying questions for Christians, as well as others. Obviously, none of these articles are exhaustive but we hope that they will be a helpful stimulus to your own thinking.

Frederick writes:

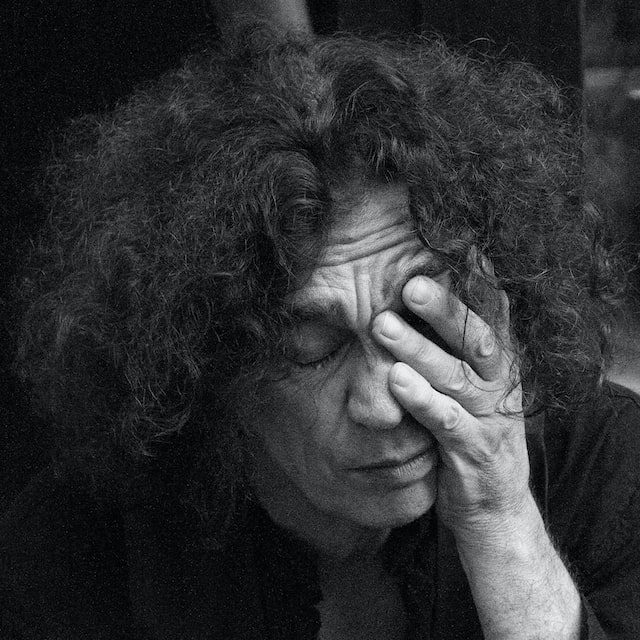

Like many of us, I didn’t grow up thinking much about the question of suffering. I had a relatively happy childhood. I grew up in a safe, suburban community – except for Eddie Fulkerson, the class bully – but everyone had to deal with Eddie.

But late in junior high school, suffering and sadness lurked around the edges of life. Our family car was rear-ended by a drunk driver and I spent 2, almost 3 years in a back brace. And in the middle of my senior year, my debate team was in a head-on collision with a two-and-a-half-ton truck. Our coach and teacher died shortly after the accident and the rest of us were hospitalized. I spent 28 days in the hospital and several months rehabilitating in a wheelchair. Since that time, I have lost both of my parents and my younger brother. And, by definition, the life of a priest is about walking alongside those who suffer.

All of this had a way of eroding any chance that I had of holding onto the sense of invulnerability that is so common in childhood and adolescence. But, of course, my experiences were trivial by comparison with what others encounter. One only needs to think of the children who deal with cancer or handicaps from an early age; the places in our own country and around the world were poverty prevails; or where war and abuse are the basic furniture of childhood to recognize how much people suffer.

I mention my own experience only to underline the fact that the question, “Why do we suffer?” is not an abstract concern but one of life’s greatest dilemmas and a question that none of us can escape.

So, although I suppose that no one can provide a final, completely satisfying answer to the question, I want to offer what I believe is a faithful, Christian answer to that question in the most direct fashion that I can.

The first thing that needs to be said is that it is not God’s will that we suffer, and God does not cause us to suffer.

It is common – even among Christians – to argue that suffering is God’s will for us and that God orchestrates our suffering. Having worked with people for years, I completely understand why people gravitate to this explanation.

When I first wrote about this subject, I was asked to give a presentation to a church near where we lived. When I argued that God does not cause us to suffer, I noticed that one couple visibly stiffened, and I could see from the look on their faces that they were angry. From that point on, I could tell that nothing I said changed their minds.

Later, I got the back story from one of their friends: The couple had struggled for years with infertility, and they had concluded that God had made them infertile in order make them foster parent children who did not have families.

So, when I suggested that God did not make them infertile, they felt that I was not just offering a different view of the relationship between God and their suffering. I was challenging a series of assumptions that lay at the heart of their own journey as a couple: The conviction that God had made them infertile, that their suffering had a purpose, that there was good imbedded in their loss.

These assumptions had made their grief easier to manage. And it provided a counterpoint to their sorrow. It also made life seem less unpredictable. But if they had the space to think about their own suffering in the context of everyone else’s, they would have realized that not everyone has the time or the opportunity to turn their suffering into a gift. And a God who dumps his children into the vortex of suffering to accomplish some other purpose cannot possibly be good.

Instead, Scripture describes suffering as givens of our existence. This includes both suffering caused by willful disobedience AND the chaos in our world that is caused by impersonal forces.

Neither the Bible nor the Christian tradition shies away from the fact that much – if not most – of human suffering is caused by our own choices or by the choices that others make. Greed, a propensity to violence, the desire for control over others, elemental cruelty — these and other behaviors cause harm and cost people their lives. Often the question we should ask is not, “Why does God allow suffering?” We ought to ask “Why do we cause so much suffering?”

And, both the Old and New Testament suggest that the natural order is disordered in wider ways by our alienation from God. Paul goes so far as to say that creation groans, waiting for the human race to be reconciled to God. Some things don’t have a direct, causal explantion. They just happen. Storms and earthquakes claim lives. Our genetic make-up predisposes us to certain kinds of disease; a momentary misjudgment can lead to a tragic accident; and our choices can have unintended consequences.

Does this mean, then, that God is not in control?

I don’t think so. But what I do believe is that God is not in control of our lives in the simple ways we imagine. Understandably, we equate God’s power or “sovereignty” with absolute control over everything. If we were God, no one would think, do, or say anything that we did want them to think, do. or say.

But from the very beginning of the biblical account of God’s relationship with us, God’s power or sovereignty is worked out in response to our choices. In fact, the story begins with Adam and Eve – who are the quintessential human beings – doing exactly what God doesn’t want them to do.

And the rest of the Old Testament is arguably a story of God’s determination to find us, care for us and deliver us, despite of our choices. Even those that the Bible describes as exemplars of faith, are fallible people who not only mistakes, but clearly ignore God, from time to time, including Abraham, Issac, Jacob, and David.

But Scripture does not expend any effort offering a philosophy of suffering. Instead it offers a picture of a God who – in the person of Jesus Christ – enters into our world, shoulders our suffering, and leads us through that suffering into his life.

Beyond the gospels themselves perhaps no one has ever captured that message in more vivid terms than the Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky. In his book, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky tells the story of “The Grand Inquisitor.

The basic plot is simple: Jesus returns to earth, in sixteenth-century Seville during the Spanish Inquisition. [He] is on the streets ministering to the poor and needy, and healing the sick. An old cardinal known as the Grand Inquisitor orders his guards to seize the Savior, intent on having him burnt the next day in the public square as “the vilest of heretics.”

The old man visits Jesus’ prison cell to accuse him of placing the intolerable burden of absolute freedom on poor, feeble, depraved humanity. It is better to offer people what they want most—the bread of the earth—rather than what they need most, bread from heaven. The terrible truth is that human beings cannot bear the burden of freedom. “There is nothing more seductive for man than the freedom of his conscience,” the Inquisitor explains to Jesus, “but there is nothing more tormenting either. And so, instead of a firm foundation for appeasing human conscience once and for all, you chose everything that was unusual, enigmatic, and indefinite, you chose everything that was beyond men’s strength.” … the nature of humanity [the Inquisitor argues] to surrender liberty to gain security….

[It is] “Better that you enslave us, [and] feed us,” [is the people’s cry, says the Inquisitor and that is why I am having you executed…. When the old man finishes his diatribe, Jesus says nothing but leans forward and kisses the old man…

[It is that]… kiss changes everything. The Inquisitor releases Jesus demanding he never return.

As with any great story, it is impossible to completely exhaust the story of the Grand Inquisitor, any more than one can exhaust the meaning of the Gospel.

But the core truth of the story is this: God does not answer our suffering with a theory or a philosophical explanation. God does not use our suffering or explain it away. God, in Jesus Christ, enters our suffering, struggles with us, grieves with us, is wounded alongside of us. And because the suffering Son of God conquers the power of death, we live in hope.

This means that the church’s calling is to share this message. It means that we ought to be careful to remind people that the Gospel is a word of hope offered in the middle of suffering. And – where we can – we are called to and we are obligated to oppose those forces that lead to human suffering.

But above all, it means that our lives as members of the Body of Christ should make the kiss of Christ — God’s love for us, God’s presence with us — a reality to others. This means coming alongside those who suffer. It means being willing to hear their pain and do what we can to ease their pain.

I have often wished that I could have conveyed that truth to the young couple in the classroom. Their infertility was not God’s doing. But the fact that they put themselves back into God’s hands, the fact that they opened their home to children without a home, the fact that they drew on their pain to ease the pain of others – that was the kiss of Christ. And they did not need the logic that God forced suffering on them, to arrive at that place.

May we all look for those opportunities in our own lives and share the good news of that opportunity with others.

Gracious Lord, God of the incarnation and the cross, the companion of the suffering, the embodiment of love – broken for us at both the cross and at your altar – make us willing participants in your reconciling work in the world. In every moment of peril, prompt us to put our lives back in your hands. Make us available to those who suffer and struggle. Enable us to listen, to be instruments of your compassion, to be defenders of the helpless. We know that it is your life, your path, your sacrifice alone is equal to the world’s pain. Lead us into lives that conform to your example and offer that hope and healing that can only be found in you. Amen.