Few people have paid the price that Salman Rushdie has paid for his dedication to telling the truth. The implicit criticism of Islam imbedded in his book, Satanic Verses, earned him a fatwa calling for his assassination. And, after a prolonged period of good fortune, in August of 2023, he suffered a near fatal knife attack that cost him his sight in one eye. One has to take seriously that kind of sacrifice and the insights that follow from it.

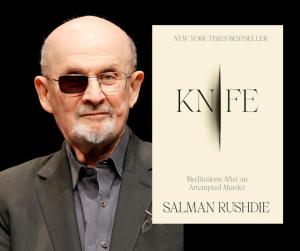

But in his book, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, Rushdie reiterates a questionable premise that he defended after the Charlie Hebdo murders:

Religion, an ancient form of unreason, when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms. Religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today….’Respect for religion has become a code phrase meaning ‘fear of religion.’ Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect. (p. 201)

Given Rushdie’s hard-earned stature as a public intellectual, it is easy to glide over his words and simply offer a hearty affirmation. And, as it applies to the importance of criticism, I think that he on solid ground – though I am not sure that criticism or debate has ever benefited from “disrespect”.

That said, Rushdie slips all too easily from “Islam,” to “Islam under the influence of totalitarianism,” to “religion” in general. And he clearly begins with the premise that religion is – by its very nature – “an ancient form of unreason.” Here there is a great deal here to debate, notwithstanding Rushdie’s journey.

One, religion is not – by nature – a form of “unreason”. To be sure, most – if not all- forms of religion are predicated on convictions that cannot be tested, using the scientific method. But this does not make religion a form of “unreason”, any more that the assertion that life and well being is sustained by love is a form of unreason. A good deal of the deepest and most important convictions we hold to be true are of that nature. And, in fact, in our own case in the west, the Judaeo-Christian tradition, not our Greco-Roman forebears lie at the heart of those convictions. Even atheists attempt to talk about and justify notions of meaning, despite the randomness of existence that their position implies; and no one would refer to their position as unreason.

Two, threats to freedom and wielding oppression is not a function of religious belief. It is a human failing. Self-consciously anti-religious regime’s, including the Soviet Union, Communist China, and other religionless regimes, demonstrated that they are capable of violence, cruelty, bloodshed, and oppression. Religion does not have the market cornered on ideologically driven violence.

Rushdie’s observations about Islam are more difficult to parse. It can certainly be argued that totalitarian understandings of Islam are a particular challenge, and it has been a challenge for quite some time (https://centerforinquiry.org/blog/the-totalitarian-nature-of-islam/). But in ways that are not true of Judaism or Christianity, Islam is – by nature – devoted to social and political control as part and parcel of its religious self-understanding.

The word siyaasah (translated above as political outlook) comes from a root (saasa) meaning to become in charge and take care of something, which means looking after something in a manner that maintains its well-being. The phrase sawwasahu al-qawm refers to people appointing someone to run their affairs….

Ibn Khaldoon defined as-siyaasah ash-shar‘iyyah [siyaasah on the basis of Islamic teachings] as follows: [It means] to lead the people in accordance with shar‘i guidelines, in a manner that serves their interests in the hereafter as well as in this world, for their interests in this world are connected to and may serve their interests in the hereafter, because the Islamic guidelines concerning the life of this world are connected to what serves people’s interests in the hereafter. Thus as-siyaasah ash-shar‘iyyah, in reality, means acting in the stead of the Messenger in guarding religious affairs and taking care of worldly affairs….

Based on that, siyaasah is an indivisible part of Islam, and there is no separation between siyaasah (politics) and deen (religion).

Based on the above and on modern usage of the word siyaasah, we may say that the Prophet (blessings and peace of Allah be upon him) used to conduct the people’s affairs and run the affairs of state on the basis of wise politics (siyaasah), because he brought a set of laws that were aimed at achieving what is in people’s best interests and warding off what is harmful and bad.

This is also how the Rightly Guided Caliphs and leaders of guidance after him ran the affairs of the ummah….

And Allah knows best. (https://islamqa.info/en/answers/181673/politics-from-an-islamic-perspective)

So, if such an astute writer, like Rushdie, introduces so little nuance on the subject of religion, what are the implications?

One, as Peter Jennings observed years ago, subtle understandings of religion are hard to find, and until that problem is addressed, nuance will continue to disappear from conversations about it.

Two, an improved understanding of religion would help to keep people from equating religion with humankind’s worst instincts. Religion is, in fact, often the wellspring of humanity’s greater impulses.

Three, religion cannot be minimized as a force in human affairs, and our failure to recognize this has bedeviled policy decisions.

Four, having said all of this about religion as a category, individual religions are not just “all the same,” and any reliable understanding of religion will require an understanding of individual religions.