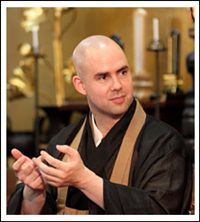

It’s a pleasure to introduce Koun Franz to you as a guest blogger. This is great fun for me because Koun is fine, young priest and in my crystal ball, I see him as an important emerging figure. He’s 100% shikantaza, Japan-Soto trained. This background gives him quite a different perspective, I think you’ll agree.

Koun was born in Helena, Montana, but has spent more than half of his adult life in Japan. From 2006 to 2010, he served as resident priest of the Anchorage Zen Community (some of his talks can be found on their website). Two years ago, Koun and his family moved back to Japan (Kumamoto), where he studies, trains, lectures, and does Buddhist-related translation work.

I encourage you to read this post through (and the upcoming offering on authentic practice) and mix it up with Koun by making a comment or asking a question.

Here’s Koun:

In his post of January 14 (“More on Koans and Who Gets to Comment”), Dosho wrote, “This mode of interpretation, btw, may be largely a Western invention as a Japanese-trained priest once told me. Kind of literary interpretation, I think he said, which he’d never heard in a dharma talk in Japan.” That priest is me. After some email back and forth, Dosho very generously suggested that I expand on a couple of our exchanges directly, as a guest blogger. I’m honored.

The conversation in question took a place a couple years ago in Alaska, when Dosho was visiting the Anchorage Zen Community. Specifically, we were discussing a style of dharma talk in which a classical Zen text (maybe Dogen, maybe a koan) is juxtaposed with something from Western literature, maybe a Stevens poem or a Dylan song. In my limited exposure to Western Zen teachers, I have bumped into this style of talking quite a few times, but in all the years in Japan, I have never heard anything even remotely similar.

For that matter, I have never even heard a Soto Zen teacher in Japan talk about a koan–as a koan, that is. I cannot recall any teacher using the word “koan” to introduce a story. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t part of the conversation. I recently watched a lecture on koan literature by T. Griffith Foulk from the Dogen Conference held last year, and in it, he explains how new research is showing that Dogen is constantly referencing both known and obscure koans in his writing, to a degree far beyond what we previously knew. In the talks I hear in Japan, the famous exchanges and awakenings do occasionally come up, but they are presented as illustrative stories, as a part of our history. They are a launching pad for expression of the dharma, but then, what isn’t?

In Japanese Soto Zen, there are a few different categories of what we might generally call “dharma talks.” The following terms are defined differently according to region and individual, but the categories stand:

• Houwa (法話, literally “dharma talk”). Houwa are usually short talks given to laypeople on the occasion of a private ceremony, such as a wake. There might be a discussion of impermanence (and how death is like the changing of the seasons), but what’s being conveyed is more emotional than philosophical. (I have heard many priests, especially those in small towns, express their exhaustion at trying to come up with something new to say in houwa when the same people attend every single funeral. It’s a kind of performance, one that a priest might have to repeat every month or even every day.)

• Sekkyou (説教, “expounding on the teachings”). These talks are also directed towards laypeople, but the teacher is usually invited, and the event is often a larger annual ceremony (such as one marking the Buddha’s enlightenment). The tone is usually encouraging, and the message is a simple one. There is actually a testing process by which one can receive various ranks as a lecturer, and since the lecturer’s audience is almost always a new one, it’s possible to repeat and polish the same basic talk for years. (I have given quite a few of these talks in the last few years; I assume that people hope the novelty of a foreign lecturer will bring more people to the temple that day. The expectation is that I will explain how I—of all people—became a priest, and that I’ll tell interesting stories about feeling out of place in Japanese culture. I always disappoint by talking about Buddhism.)

• Houyaku (法益, “benefit of the dharma”). This is the kind of talk you might find at a genzo-e (Shobogenzo study group) or at a monastery. Houyaku tend to be very academic in nature, picking apart a text line by line while adding information about its historical context, its application in a monastic setting, and so on. Teachers who are “good at” houyaku must be very knowledgeable, but unlike the categories above, there is no expectation that a houyaku will be inspiring or polished or even engaging. It is a class, not a performance.

• Teisho (提唱, “a proposal”). It is rare to hear teisho in Japan, but this is the category that corresponds most closely to what people in the West call a “dharma talk.” In my experience, the context in which one is most likely to hear teisho is during sesshin, while people are actually sitting in zazen. An in-depth discussion of zazen and true moment-to-moment practice would be surprising in any of the above categories, but since teisho are so often delivered during periods of sitting, zazen is a favorite topic.

Skillful or not, interested or not, all priests who do temple work related to laypeople will deliver houwa, perhaps frequently. A particularly charismatic or respected or even just confident (oh—or foreign!) priest will probably receive some invitations, in the course of his career, to do sekkyou. Houyaku is the realm of those who are particularly well educated, or who have become specialists in one or more areas of the tradition. And teisho is the domain of a very limited few, usually just the officers of monasteries. The vast majority of the priests I know in Japan will never be in a position to deliver either houyaku or teisho, nor could they imagine themselves doing so. In a country with tens of thousands of Soto Zen priests, there are people to do those things.

But I suspect that in the US, the situation is perfectly reversed: teisho are offered almost constantly; houyaku are expected whenever there’s some kind of study group; sekkyou are for the occasional guest-speaking gig, for larger groups, and for outreach; and houwa are relatively rare. It’s not just that Western priests have to do it all (since there are so few around), but also that the audience’s expectations are completely different. (When the AZC first contacted me about serving as their resident priest, a teacher here congratulated me—jokingly—on my promotion to ikinari douchou, “instant head teacher of a monastery.” He suspected, from what he’d heard about Zen centers, that my job description would be closer to that than to the duties of an ordinary priest. And he was right.)

In 2006, when I was preparing to move to Anchorage, one of my teachers sat me down and offered this advice: “Always stand in your position.” What he meant, essentially, was to accept the role of being a priest, not to apologize for it. It’s easy to refuse to sit in the high seat, to laugh at the silliness of having everyone bow in your direction, to wink and say in a thousand little ways, “Don’t worry—I know we’re just playing. I’m just like you.” People practically beg you to do it. But my teacher’s stance was, and is, that deep down, people do not want the priest to be just like them. They want that person to have the strength to sit in the position of the Buddha, unflinchingly, and to speak and act from that place. Because who else will do that?

“Stand in your position” means to open your mouth and let it fill with the dharma, to put on the robe of the Buddha and to embody the lineage stretching back to the Buddha, with no excuses. It also means to accept the projections and transference of others—as father figure, as distrusted school principal, as saint, as charlatan—without stepping outside of your role to say, “No, no—I’m really this.” It is not about being stubborn or immoveable; it is a question of knowing one’s function and realizing that function wholeheartedly. It is a way of offering yourself to others.

In my whole life, no single phrase has permeated my consciousness in the way that “Stand in your position” has. It pokes me every day—not just in the role of Zen priest, but also as an educator, as a citizen, and recently as a father. It is incredibly difficult—in part because there are so many tempting excuses not to do it, but mostly because in order to stand in one’s position, you must first understand, even if only intuitively, what that position is. Even if you cannot fully know what to do, you have to do it anyway.

I bring this up because as I kick around the questions Dosho raised about commenting on koan literature, I keep coming back to this issue of position. Who gets to talk about what, and how? I don’t know who gets to talk about what. I’ve been thinking about it for days, and my perspective keeps shifting. In some cases, maybe it’s better to say nothing. Perhaps just the word “koan” can mislead listeners to believe that they are entering an entirely different kind of dialogue, one the speaker does not intend. Could it be that simple? I’m not sure about that. But if we do open our mouths, if we do take that leap, if we stand in that position, then I am sure that part of that function is to speak with the full thunder and music of the Buddha’s own voice. We do this while not knowing, because not knowing is our fundamental condition. But we do it. We just do it. Because who else will?