This question has been up again for me lately because of a couple opposing currents that I’ve noticed in the culture and my work world, namely careful process monitoring vs. the results only work environment.

This question has been up again for me lately because of a couple opposing currents that I’ve noticed in the culture and my work world, namely careful process monitoring vs. the results only work environment.

So here’s a quick bit about these and their relevance for Zen training.

I’ve long felt that the “Zen Master” title gets flung around way too wantonly in the West, btw, so let me confess that prejudice at the outset.

Malcolm Gladwell wrestles with the issue of mastery in his usual entertaining manner in Outliers: The Story of Success. His basic point being, it seems to me, that in order to achieve mastery, or at least success, we need to put in our time hacking away and then be lucky with how all the forces beyond our puny efforts are rolling out.

The Beatles and Bill Gates, for example, did their hours of practice (the hairy four guys in strip clubs in Berlin) and were really fortunate to have a bunch of societal circumstances ripening just when they were.

Malcolm and others note that what lots of folks who have achieved extraordinary accomplishments have in common is that they practiced a lot. Like at least 10,000 hours.

Applied to Zen, 10,000 hours would mean about 600 days in sesshin – if you don’t count sleep. Without sesshin, it would take longer, of course. If you sit for an hour a day, it would take about 27.39 years to log 10,000 hours. If you sit 15 minutes a day, that’d be 109.6 years. Individual cases would get rather complicated weighing both factors. I did the rough math for the first 13 years of my practice while Katagiri Roshi was alive and thanks to the power of rounding up and hind-sight estimating, came up with a rather large number that I won’t share. I’m just too humble.

Like for other things, I think that the 10,000 hours rule is probably a necessary but insufficient condition for mastery in Zen.

Granted, there are problems with the math like how to count hours of “practice,” for example, so I’ve included 18 hours a day in sesshin and the full period of zazen, not subtracting those days that we’re zoned out ninety-some percent of the time! Then too there’s how to count monastic training. And there’s a lot more to a Zen life than the time you log in sesshin or in daily formal practice. But for me the exercise puts mastery in some perspective.

One of the Zen teacher organizations asks the question to applicants about how many days of intensive retreat they’ve done and friend who’s a member of the membership committee thinks that the unspoken minimum is about 300 – a rather long way from the 10,000 hours, no matter how deep the samadhi.

Btw, another friend and member of the membership committee denies that there is any such unspoken number. Hmmm.

The counter-current has a recent expression in ROWE – results only work environment. See Why Work Sucks and How to Fix It: The Results-Only Revolution by Ressler and Thompson for more. They work for Best Buy and write about how they’ve implemented this approach there. The basic deal is that it doesn’t matter how many hours you log, whether you show up for work or not, whether you log 10,000 hours, etc., it only matters if you achieve your goals.

They write about one guy who is a roadie for a rock band, traveling around the world, doing his techy thing for Best Buy at the same time. He apparently is really happy and a very dedicated worker.

Btw, I’ve sent an application to Lucinda Williams to see if she’ll accept me as a roadie and then I’ll be talking to my boss. Wish me luck.

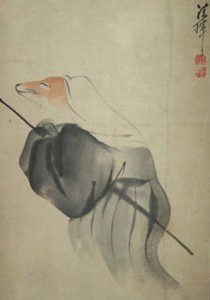

Anyway … the rub with the results-only approach to Zen practice is the difficulty in identifying the results or at least agreeing on them, as recent posts and comments here indicate. For Soto Zen the process is the result. For koan Zen, there’s passing through the many koans. But both of these also seem like necessary but insufficient conditions.

Then there’s manifesting a tender broken hearted love in daily life, carrying the many beings across, etc., which are hard to measure but you might know them when you see them. This seems to be the orientation of traditional Soto Zen in leaving it up to the community to call someone “Roshi” (old teacher), when the community senses that the person is ready rather than the person him/herself or their teacher laying it on them.

So no conclusion so far.

Katagiri Roshi always denied being a “Zen Master” and didn’t like people to call him that. He said that being a Zen master was like being a master driver of the car. The moment when you say, “I am master of driving the car,” you are not paying attention to your driving and might cause an accident.

That seems like a good thing to keep in mind.