What’s the point of study in Dogen Zen?

What’s the point of study in Dogen Zen?

Given my Dogenophile disposition, I’m asked this question from time to time, and especially now that I’m developing an online study program, Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training (which is full, btw, so if you’re interested in doing this work, stayed tuned for openings or contact me in a couple months).

The point, of course, is practicing enlightenment.

You might wonder, “How the heck does reading some illogical stuff contribute to practicing enlightenment?”

Likewise, some shave pates suggest that the point of Dogen Zen is to not make sense.

In the Mountains and Rivers Sutra, Dogen says about those who hold this view, “The illogical stories mentioned by you bald-headed fellows are only illogical for you, not for Buddha ancestors. Even though you do not understand, you should not neglect studying the Buddha ancestors’ path of understanding. Even if it is beyond understanding in the end, your present understanding is off the mark.”

He also says that those who hold the view that the buddhadharma is illogical are immature, foolish, have never truly studied, and are really, really stupid. So there.

Dogen says this in regard to the views of monks he met in China regarding Nanchuan’s sickle, Huangpo’s staff, and Linchi’s shout. Presumably, shorthand for the koan tradition.

If there is an understanding that is understandable to Buddha ancestors, how does it unfold? What is the inner path of this undertaking?

An old friend, a black-belt in Shotokan Karate, told me in that tradition there are three stages – birth, mastery, and breaking. That fits Dogen Zen work quite well – and I’d add a fourth stage: flapping with vitality.

When most of us are born in this Zen work, it’s like coming home. We find in the buddhadharma an expression of what we’ve always intuitively felt about this life. And because it’s so damn ungraspable, we try to figure it out with our intellect while we while away the time in zazen. Fortunately, from time to time, we follow the instructions and let go of our thinking. In letting go of thinking, we discover a more and more subtle quality of thought.

Through perseverance, increasing intimacy and grace, we suddenly find ourselves pivoting mysteriously. We bridge the gap and are no longer looking at the buddhadharma from the outside. This is mastery.

And then to our surprise we find that in order to live the buddhadharma, what we have mastered must be broken, or rather, we find that we and it, we-as-it, have always been broken. And in the perfection of brokenness, we are no longer bound by the tradition so it can be expressed freely.

What’s left but to flap along with vitality, cursing the gods and buddhas, howling with the coyotes and the far-off train whistle on a hot summer night?

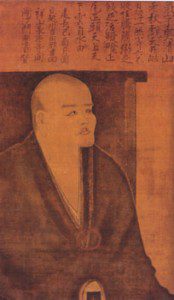

Speaking of howling, the picture above is a self-portrait by Dogen, probably from 1249, just a few years before his death. He painted it on the night of the harvest moon and wrote a poem for it while he was feeling good (the calligraphy at the top of the painting). Okumura and Leighton (Dogen’s Extensive Record, p. 602) translate it like this:

Autumn is spirited and refreshing as this mountain ages.

A donkey observes the sky in the well, white moon floating.

One is not dependent;

One does not contain.

Letting go, vigorous with plenty of gruel and rice,

Flapping with vitality, right from head to tail,

Above and below the heavens, clouds and water are free.

May we all go on practicing enlightenment just like this.